Corliss Bean1, Tanya Forneris1

1 University of Ottawa, Department of Human Kinetics, Canada

Citation: Bean, C., Forneris, T. Exploring stakeholders’ experiences of implementing an ice hockey programme for Inuit youth. Journal of Sport for Development. 2016; 4(6): 7-20.

Abstract

The Nunavik Youth Hockey Development Program (NYHDP) is a sport-for-development programme designed to provide Inuit youth with opportunities to be physically active and develop life skills. The purpose of this study was to use a utilization-focused approach to conduct a formative evaluation, which explored stakeholders’ perspectives of ongoing successes and challenges of programme implementation. From interviews with 13 stakeholders over the course of one season, as well as document analysis, two main themes emerged pertaining to programme implementation: successes and challenges. Sub-themes related to programme successes included strong programme fidelity due to a well-planned structures, a stable organizational structures, increased local appropriation, increased participation rates, and the NYHDP’s positive impacts on the region. Subthemes related to challenges included the need for more reliable human resources, difficulties in maintaining a formal partnership between the NYHDP and school board, and implementation costs. This paper also includes practical implications, recommendations, and future directions for the programme. Overall, this evaluation represents an important step in responding to calls for increased process evaluations of sport-for-development programmes, particularly in Aboriginal contexts and aids in understanding the successes and challenges of how to deliver a youth hockey programme in a rural context from the perspective of various stakeholders.

Background

Ice hockey (hereafter referred to as ‘hockey’) has been an integral part of Aboriginal culture for decades.1,2 While Inuit people have been playing this sport for many years, few organized programmes exist for Inuit youth in Canada.3,4 Research has shown that sport has been effective in keeping Aboriginal youth out of trouble.5,6 Needs assessments conducted with youth in rural Aboriginal communities have indicated the desire for organized sport and a safe, fun place to be physically active.3,4 However, numerous challenges have been identified pertaining to sport access including facility locations, minimal support staff, and financial costs for programs and equipment.7 The Nunavik Youth Hockey Development Program (NYHDP) was established in 2006 with the purpose of utilizing hockey as a vehicle to enhance physical and psychosocial development of Inuit youth8 with the goal of minimizing such barriers.

It has been argued that conducting programme evaluations in northern and remote Aboriginal communities is challenging due to issues surrounding accessibility and cost.9 Only a few studies have been conducted in recent years. For example, Halsall and Forneris10 evaluated a youth leadership programme that was part of Right to Play’s Promoting Life-skills in Aboriginal Youth (PLAY) programme implemented within 57 communities across Ontario, Canada. Results revealed that the mentors perceived the programme as having a positive impact on youth, enabled personal growth of mentors, and increased community engagement. Moreover Blodgett et al.11 partnered with Aboriginal community members to understand the cultural struggle related to retaining Aboriginal youth in sport. Promoting Aboriginal role models and developing a broad volunteer base were identified as useful strategies. Although these two studies are promising, there is much to learn about the implementation of effective programming in Aboriginal youth sport contexts; therefore, this study aims to assist with this gap.

An organization’s ability to effectively deliver sport for development (SFD) programmes with individual and community development outcomes is influenced by many factors, including available human and organizational resources.12-15 Researchers have also noted challenges related to sport and programme delivery, monitoring, and evaluation, highlighting concerns regarding the likelihood of achieving various objectives such as building a sustainable and effective programme for youth within communities.16 As a result, Skinner and colleagues17 discussed the importance of engaging and working collaboratively with multiple partners that support programme goals and outcomes, assist with delivery, and provide funding. Thus, this formative programme evaluation research utilized such an approach whereby the researchers worked in collaboration with NYHDP stakeholders during programme implementation with the aim of understanding and improving the programme for future implementation. To ensure this, a utilization-focused evaluation was employed.

A utilization-focused approach involves researchers and stakeholders working together so that stakeholders can better understand the evaluation process and subsequently use the evaluation findings for future decision-making regarding a programme.18,19 Many SFD researchers have advocated for this approach as they recognize that evaluations are only effective if findings are used in a meaningful way towards programme improvement.220,21 Moreover, utilization-focused evaluations have been successfully applied to various youth programming contexts.22-24 For example, research has used a utilization-focused evaluation within youth programming pertaining to physical activity,23 conservation education,24 and mental health.22 Within these studies, researchers were able to meaningfully engage stakeholders in the evaluation process and work with them to adapt programme goals to better meet participants’ needs.222,23 While a utilization-focused approach can involve both formative and summative evaluations, the authors agreed that this study called for a formative evaluation given the lack of research in this area as well as a lack of understanding of the strengths and challenges experienced in NYHDP implementation.

Programme Description: Nunavik Youth Hockey Development Program

The NYHDP was established with the purpose of being a crime prevention programme while using hockey as a vehicle to enhance the development of Inuit youth.8 The NYHDP was developed by a retired professional hockey player with the overall goal to limit negative behaviours in addition to encouraging youth to be physically active and make positive life choices (e.g., stay in school, put forward their best effort in life) that enable them to succeed in the future.5 To accomplish this the NYHDP utilized a strong staff base and intentionally integrated the teaching of life skills and educational activities into various components of the programme. In addition, all programme components and stakeholders involved in programming emphasize and enforce the importance of making positive life choices and are outlined in detail below. Therefore, based on Coalter’s25 classification of sport-in-development, the NYHDP is a plus sport programme.

The NYHDP commenced in 2006 and interested youth aged 5 to 17 years of age in all villages within Nunavik were invited to participate. The NYHDP is offered to these youth at no cost, since all programme expenses (e.g., human resources, equipment, travel costs, ice rentals) are covered through various levels of government and private sector funding. One of the key stakeholders involved from programme outset was the regional school board. From 2007-2012, the NYHDP had a formal partnership with the school board, whereby stakeholders (i.e. principals, teachers) at all schools across the region enforced policies related to effort and participation in school, similar to NYHDP goals, to illustrate the direct link between school hockey for youth. These policies included the necessity for youth to attend and put forth their best effort in school if they wanted to engage in the NYHDP. Teachers and principals were responsible for completing a ‘hockey report card’ for individuals involved in the NYHDP which assessed their attendance and effort within the classroom. Prior to the 2012-2013 season, the partnership was formally eliminated because it was discovered that not all schools across the villages were implementing the policy consistently and that some teachers were using the policy as punishment as opposed to encouragement or as a way to further engage youth. Another issue recognized by many stakeholders was that by having this policy, the programme was excluding some of the most at-risk youth within the villages who were not attending school due to various circumstances (e.g., abuse, neglect). The director wanted to ensure that these youth were not excluded as it is the most at-risk youth who may have the greatest need for such a program. As a result, the coaches across the villages were encouraged to gain an understanding of youth in their respective villages and understand their background and family circumstances. Such an approach would consequently enable coaches to best engage and work with each individual youth to help provide a safe and supportive environment that also encourage youth to make positive life decisions, work hard, and make a commitment to the programme.

The NYHDP is comprised of two main components for youth: recreational hockey and competitive hockey. The rationale for these two components is to be inclusive as the goal of the programme is not to strengthen hockey, but rather to foster the development of youth in these northern villages. Both programmes help to ensure that all interested youth are able to participate while at the same time provide access for youth who want to be involved in a more competitive programme the opportunity to do so; in northern Aboriginal communities, this type of competitive programme is rare. Tied to both of these components is a third element: the certification of Local Hockey Trainers (LHTs). These two components and the certification process are described below.

Recreational hockey. The goal of the recreational component is to provide the opportunity for youth of all ages, genders, and abilities throughout Nunavik to engage in a structured sport programme designed to enhance their overall development. In each village, an indoor arena is open to youth afterschool and in the evenings. Many of the arenas are accessible to youth by foot, minimizing accessibility barriers, and are typically open from October to April. Exact participation rates cannot be recorded in each village because participation varies across villages and from night-to-night, but it can be estimated that an average of 20 to 30 youth attend for all age categories per village each night. Recreational programme delivery differs slightly across villages based on resources (e.g., human, time, space); however, in most communities there are two on-ice sessions per night where girls and boys participate together, yet are divided by age groups. Due to village size and fluctuation in participation, teams are created on a night-by-night basis allowing for structured free-play in the form of scrimmages.

Given that the NYHDP was designed as much more than a hockey programme, the coaches are trained to discuss and also be role models of positive life choices (e.g., never giving up, putting forth their best effort, attending school, avoiding drugs and alcohol). In 2011, regional tournaments were integrated into recreational programming to provide participants opportunities to travel and play hockey with youth from different villages. Five tournaments (one for each of the five age groups described below) are held each season with opportunities for each village to enter a team. These tournaments are used as incentives for youth not involved in the competitive component to continue to attend and put forth effort in school in order to participate as youth are selected based on their commitment to the programme within their village and not solely their hockey skills.

Competitive hockey. This component is comprised of five teams broken down by age: Atom (9-10); Peewee (11-12); Bantam (13-14); Midget (15-17). There are four boys’ teams based on these age groups and one girls’ team, which combines Bantam and Midget. Girls between 9 and 12 are also able to try-out for the boys’ teams; however few do. At the time this study was conducted, each team would participate in two tryout camps and once final rosters were selected, a week-long training camp is held. The tryouts and training camps are held in Nunavik’s largest village and all youth interested in attending tryouts are flown from their respective villages.

As with the recreational component, the focus is not only their improvement of hockey skills because all youth also attend educational sessions as part of the competitive component. These educational sessions are 90 minutes in length and are implemented daily during all try-outs and training camps for the competitive program. A pedagogical coordinator is in charge of the sessions which involve the intentional teaching of life skills (e.g., responsibility, self-control, positive attitude, confidence), activities for team bonding, and lessons related to healthy life habits (e.g., nutrition, drug and alcohol use, sleep, physical activity). Youth are selected for the competitive teams based on their skills on the ice as well as their level of engagement and commitment to the educational sessions during the try-outs and training camps. Youth that are selected then travel with their respective teams to major cities in Québec or Ontario where tournaments are held. Each competitive team participates in one tournament per season, which allows youth to experience different teams and cities. Structured life skills activities remain a primary element and are integrated during the tournaments in which similar activities facilitated during tryouts are run during a 90-minute session each day.

Training and certification of coaches. The final component is the training and certification of LHTs who complete the Hockey Québec Coaching Certification, a provincial training programme that enables individuals to attain knowledge and tools to be able to work effectively with athletes. These individuals are current or past NYHDP participants, ranging from 15 to 35 years old, and are mostly of Inuit descent. Previously, most LHTs were male, yet within the 2012-2013 season females also participated in the training. LHTs serve as village coaches who run practices and are seen as role models for younger participants.

Since its inception, there has been no formal evaluation conducted on the NYHDP. Plans to continue and expand this programme highlighted the need for an evaluation to understand the processes of implementing such a programme. Understanding how a hockey development programme influences the region could provide a reference for other Aboriginal populations to develop similar programmes and also begins to address the lack of research on SFD initiatives implemented with Aboriginal youth in Canada. Thus, the purpose of this study was to use a utilization-focused approach to conduct a formative evaluation by exploring stakeholders’ perspectives of ongoing successes and challenges of the NYHDP implementation.

Method

Context and Participants

The researcher was Caucasian, had an extensive background in hockey and gained an inside perspective of the programme through engaging in 50 days of fieldwork over the course of one hockey season. During this time, she actively participated in on-ice and educational sessions as a coach and was involved at the recreational and competitive levels to thoroughly understand the structure and processes of the programme. Throughout her involvement, she engaged in six competitive tryouts and training camps, spent one week each in three villages learning about the recreational programmes, and spent one week travelling with a competitive team to a tournament.

Thirteen stakeholders participated in the study: one programme director, two coordinators (regional and pedagogical), five coaches, two school principals, two parents, and two youth. The sample consisted of nine male and four female participants and their length of involvement in the programme ranged from one to seven years. Four stakeholders resided outside of Nunavik but were core NYHDP staff. On the other hand, nine participants were Nunavik residents and lived in four different villages. Some participants were directly involved in the programme (i.e. coach, coordinator, youth), while others were more indirectly involved (i.e. parent of youth participant); however, each stakeholder had a sound understanding of the programme.

Data Collection and Procedure

This study used a utilization-focused process approach by examining NYHDP implementation. Transcripts from semi-structured interviews with programme stakeholders, recreational reports, and session log sheets were used as primary sources of data. Logbooks were used as a secondary source of data, providing more background context of the programme’s evolution for the researcher.

Semi-structured interviews. Thirteen semi-structured interviews took place during the 2012-2013 season in-person (11) or via phone (2) with the purpose of understanding stakeholders’ experiences of the NYHDP. In-person interviews took place at convenient locations (e.g. hockey arena, school) and times for participants. One interview guide was created that explored their experiences in the NYHDP, successes and challenges of programme implementation, and suggestions for programme improvements across the region. Moreover additional questions were contextualized to each stakeholder based on their role within the NYHDP and probes were used to further explore participants’ perceptions (e.g. principal: How has the NYHDP been working within your school?; parent: How do you believe the NYHDP has been perceived by your son/daughter?; How have they been impacted by participation?). Interviews ranged from 20 to 100 minutes and were recorded using a digital audio-recorder.

Document analysis. Three types of documents were used, which provided a deeper and complementary understanding of the experiences expressed through stakeholder interviews. First, six existing organizational logbooks (i.e. documentation of processes, on and off-ice plans, outcomes, participation rates, training regimes, emails) of each season since the programme’s inception were provided by the host organization and analyzed to provide a sound historical background on the programme. Second, recreational reports completed by implementation agents over the course of two seasons (2011-2013) were analyzed. A total of 101 reports (74 from 2011-2012; 27 from 2012-2013) were analyzed. The report template was created by the NYHDP Director as a tool to internally evaluate the recreational programme component across all villages and consisted of the same six open-ended questions that explored different stakeholder involvement within the programme and processes that took place in each community: What involvement was there from the municipality? (e.g. School? Parents?; What was the condition of the arena?; Can you provide recommendations to improve the programme?). Third, programme session log sheets completed by coaches and pedagogical coordinators throughout the 2012-2013 season during on-ice and educational sessions were examined. The log sheet was specifically designed by the lead researcher to measure programme fidelity, in other words, the extent to which the programme was implemented as planned. The log sheet was completed at the end of every programme session and included five close-ended questions that measured the extent to which the planned activities were implemented, if objectives of the sessions were achieved, the extent to which activities and objectives of the sessions were implemented as planned, and the extent to which the participants were engaged. A total of 141 log sheets (34% on-ice hockey sessions, 66.0% educational sessions) were collected and analyzed.

Data Analysis

Interview transcripts, recreational reports, and session log sheets were used as primary sources of data, and logbooks were used as secondary sources of data that provided researchers with more background context of the programme’s evolution. Data triangulation was employed as multiple stakeholders (coaches, principals, parents) and multiple methods (interviews, log sheets) were used to collect data. Maxwell26 argued that the use of multiple sources and methods provides a more in-depth and accurate interpretation than solely one source or method. The qualitative data (i.e. interview transcripts and community reports) were analyzed based on previously established guidelines and a collaborative approach to analysis was taken to ensure trustworthiness of the data.27 Specifically, an inductive thematic analysis26 was used which allowed themes to be established and further classified into two main categories: successes and challenges. The first author completed the first round of analysis, followed by the second author who verified themes. Researchers discussed and debated discrepancies until they reached agreement. Identification codes were created for quotations as a means to identify participants and ensure anonymity (sometimes limited) and confidentiality. Quotations taken from reports were identified by report dates. Quantitative data (log sheets) were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 and descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated.

Results

The results are presented in two sections, which outlined the perceived successes and challenges of programme implementation by NYHDP stakeholders.

Successes

This section outlines the identified successes of the NYHDP implementation, which include the following themes: a) Strong programme fidelity due to a well-planned structure, b) Competitive programme structures that were well-planned and implemented, c) Stable organizational structures, d) Increased local appropriation e) Increased participation rates, and f) Perceived positive impact on the region.

Strong programme fidelity due to a well-planned structure. Based on the completed log sheets during the 2012-2013 season, the majority of the time (84%), stakeholders perceived that the planned session objectives were met (e.g. introduce and practice break-out). This indicated that not only were the planned activities implemented, but the overall objectives of those planned activities were also met. The NYHDP staff typically believed that youth were engaged ‘most of the time’ (63%) or ‘all of the time’ (29%) during session activities. When youth were documented as being engaged ‘all of the time,’ it was typically during on-ice sessions whereas youth were engaged ‘most of the time’ during classroom activities. Additionally, during tryouts, there were often wait times between drills as there were several participants on-ice; therefore youth were documented as engaged ‘some of the time’ or ‘most of the time.’

Competitive programme structure well-planned and implemented. From the session log sheet analysis, it was evident that many sessions were thoroughly planned and structured. Staff had outlined goals that they wanted to accomplish at the beginning of each session and had planned activities to support and achieve these goals. For example, during an on-ice session, coaches had the goal of working on breakouts, whereas, the goal of the classroom session was to work on life skills such as goal setting, teamwork, or effort. From the 149 log sheets collected, all of the activities were implemented as originally planned by programme staff 78% of the time. The remaining sessions did not have all activities implemented as planned for various reasons. For instance, many on-ice sessions were structured as a progression of drills. If youth were struggling to accomplish a drill, coaches reported spending more time on that drill prior to moving to the next drill progression to ensure youth comprehension. Similarly, during the educational component, the Pedagogical Coordinator believed some sessions ran into time constraints when one activity took longer than planned. Some educational activities facilitated lengthy group discussions about life topics (e.g. plans for the future, healthy life habits), which resulted in further planned activities not being accomplished. Overall, the majority of activities were delivered as planned in a given session and in some cases, staff documented that there were “even more activities implemented than planned” (September 25).

Stable organizational structure. Over the past years, the NYHDP built a stable and reliable staff team, which included a full-time staff team of 10 individuals with six involved for five years or more. The Regional Coordinator was of Inuit descent and six of the staff have years of experience working in the north prior to working with the NYHDP. The Director stated: “[Having core staff group] helps to highlight the stable organizational structure of the NYHDP, especially the level of dedication and belief in this youth development programme by many people.” Similarly, Principal 2 stated: “Hockey has always been something very popular, but never organized as it is now—the way that it’s organized is very beneficial.” Not only was this stability identified as important for the internal structure of the organization, it has also had a critical impact on youth as they have been able to build reciprocal relationships with the staff who have been able to learn about youth at an individual level and work with them from year to year. Principal 1 highlighted how pertinent coach reliability has been to programme success: “It’s about working together…if there is no coach to send youth to—you’re promising the teachers we’re going to use hockey to modify behaviour—but there’s no coach. The buy-in and effect was instant in [village] because coaching staff were reliable.”

Increased local appropriation. Having increased local appropriation refers to the programme becoming more Inuit run by providing opportunities for local individuals to be involved at the organizational level, specifically related to programme delivery. In early years of the program, many staff were from southern parts of Québec and Ontario and travelled to villages to deliver the programme. Over the past years, programme staff have created opportunities which has fostered interest in many individuals within the region. For example, alternative pathways have been provided for youth as they age out of the programme (e.g. opportunities to become LHTs). Several youth still involved in the programme expressed interest in working as LHTs, which has been documented as helping to make the transition easier as they become adults. All interested individuals go through the coaching certification programme as a group at the commencement of each hockey season, which follows the delivery of a standardized provincial training program. The Director vocalized how proud he was of two long-standing participants of the NYHDP: “After many seasons in the programme, [name of youth] are taking it to a higher level; becoming hockey instructors. From 9, playing Atom back, to 16 playing Midget and being hockey instructors on top of it—really nice.” Similar to youth participation rates, the number of LHTs also increased. From 2010 to 2013, this number increased from 15 to 38 across the region, which was the most LHTs the NYHDP had since inception. Having LHTs who went through the NYHDP and were community members helped with programme sustainability, as stated by the Director: “Our LHT quality is better. It’s mostly Midget kids who have grown in the programme. It gives a chance for kids to grow within this structure and learn; this is the key to sustainability of the programme at the instructional level.”

In one of the larger villages (~2200 people), a Coordinator was hired as a full-time NYHDP staff. As the NYHDP was growing at both the competitive and recreational levels, this role was to specifically oversee the recreational programme allowing the director to focus attention towards the competitive component. Because of his involvement, there was a consistent schedule that was implemented throughout the season. Coordinator 2 went on the ice with youth and provided support for LHTs. He stated: “I’ve got time to discipline them and have them pick up their stuff. It is way more than just hockey to pick up their stuff in the dressing room: the respect of the arena—picking up their garbage—and each other. I can see a difference because it’s constant. I’m always there.”

Conversely, in a smaller village (~300 people), an individual took on the role of the Regional Coordinator of the NYHDP, a paid position that was initiated in 2011. Due to his efforts in promoting and recruiting to the programme, eight LHTs were trained and acted as village coaches at the recreational level. Parent 1 spoke of the benefit of having the Regional Coordinator: “He has been a great mentor and provides support and resources to LHTs. He’s at the arena every night with the kids.”

Increased participation rates. Participation rates for the recreational and competitive components have grown since programme inception. Table 1 illustrates the participation rates from 2006 to 2013. For the recreational level, although no concrete numbers were available as rates of participation vary from one evening to the next within each village, it was documented that an average of 20 youth per evening, per village participated in the programme. Coach 2 talked about this perceived success: “We have around 60 kids playing every day over three hours… 20 kids per session…and it’s getting more.” Villages in Nunavik range from populations of 195 to 237528; therefore having an average of 20 youth attend hockey on a given night was considered positive. The Director reinforced the importance of participation rates at the recreational level:

Over the past years, we have noted in most places that participation rates have been increasing at the community level. Due in part to those rates’ increase, we have noted that the caliber of Nunavummiut youth hockey have also increased from year to year. It seems that we have more and more interest in kids wanting to participate in the NYHDP and be part of Regional Tournaments and various Nunavik Nordiks’ hockey camps hosted in [village] each fall.

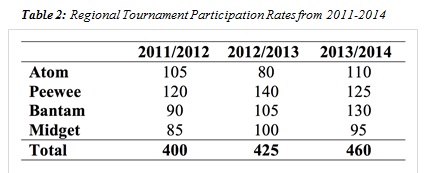

Furthermore, the participation rates have increased for the regional tournaments from Year 1 (n = 400 in 2011-12) to Year 2 (n = 425 in 2012-2013) to Year 3 (n = 460 in 2013-2014). Over the past three years, the highest participation rates have been at the Atom and Peewee levels, yet Bantam and Midget numbers have also increased over this time, which has been seen as a success, as many youth begin to drop out of sport around this age because of other interests and life demands (see table 2).

Perceived positive impact on the region. The NYHDP facilitated the development of the Nunavik region on several levels. Based on recreational reports, it was evident that in the NYHDP’s early years, money was leveraged from the province of Québec to improve conditions of Nunavik’s arenas, including renovating ice surface and boards, repairing Zambonis, and replacing broken light fixtures. Eco-Ice systems were installed in every arena to aid in the commencement of an earlier hockey season and for reliability and consistency of programme delivery. These sustainable changes have positively impacted not only the NYHDP participants, but the region as a whole.

Much media attention was garnered within the first two years of programme initiation. Having a retired professional hockey player as a Director helped facilitate initial media attention, yet as the programme became more established, the programme itself helped to bring visibility to the region. This media attention led to hockey equipment donations from all over Canada, which helped youth within Nunavik have the opportunity to play hockey that might not have been able to afford equipment.

This programme not only had a positive impact on the region in terms of physical resources, but also provided opportunities for youth to participate in organized sport and be physically active. Based on the previous theme of ‘Increased Participation Rates,’ providing such an opportunity was successful for youth within Nunavik, as Youth 1 stated: “It gives us something fun to do because we’re in an isolated place and there’s nothing much to do here.” Two stakeholders talked about how programme participation provided a positive outlet for youth: “The kids may struggle or have problems, but when they’re on the ice, they’re the kids who smile and work hard for hockey, they’re like two different kids; it really has positive effects” (Coach 3) and “NYHDP is about much more than hockey. I never needed to be ‘sold’ on the value of what the organization [NYHDP] was trying to accomplish, it has so many benefits for youth” (Parent 2). Moreover, Coordinator 1 stated:

Being in the programme, that’s what they need. Even if they aren’t doing great in school –it’s really sad that some of the kids have bad family life—even if they have this two weeks of opportunity to be here, that’s really great for them. They’re going to remember that forever…it’s good to have the regional tournaments too because you’d love to keep all 60 kids that come to the tryouts, but at least they get a chance to be involved in the [regional] tournament.

Lastly, Youth 1 discussed life skills they believed were developed as part of programme participation: “Leadership was a really big one because [coaches] reinforced it every chance they had. Also responsibility, for yourself, your choices; both in and out of hockey,” while Youth 2 spoke of the benefit of engaging in the LHT programme: “Being an LHT has helped me with what I have learned in the programme—like leadership, effort, and responsibilities. Now I can put what I learned into practice with others, like the younger kids.”

The change in partnership with the school board sparked interest in one village’s school, where the programme had been well implemented (e.g. teachers/principals supporting and enforcing the programme, high youth engagement, reliable coaches). The education staff passed a resolution at the municipal level to have recreational hockey tied to youth’s schooling. Specifically, this meant that while schooling was no longer connected to the competitive component, the municipality wanted to enforce the importance of attendance and effort in school through recreational hockey participation. Principal 1 stated: “Since there is no longer a formal partnership with the programme, the local council is reviewing our request to have a partnership with the hockey programme—for local practices and games.” The result of this resolution was documented in an email from the principal to the Director during the 2012-2013 season:

The resolution for the school/community hockey programme was passed before Christmas. Since then, there have been major improvements in school from: (names 10 students). All of these boys were at risk of trashing their school year. The turnaround has been astounding. I only had to cut hockey for one or two practices and things got back on track. Their attendance has improved, their work in class has improved. Teachers have come to see me because they are so delighted with the improvement…one mother was delighted about the improvement. The boys didn’t end up losing very much hockey, but they gained a lot in school. (January 17)

This illustrated that while the partnership was not a feasible component of the NYHDP for all villages, the initial partnership worked well enough in certain villages to want to continue this endeavour locally, as it was perceived as having a positive impact on youth involved in hockey.

Challenges within the NYHDP

Three themes emerged pertaining to programme challenges: a) Need for more reliable human resources, b) Difficulties maintaining formal partnership with the school board, and c) The high costs associated with the implementation of NYHDP.

Need for more reliable human resources. The NYHDP utilized a framework that was implemented at the recreational level, yet each community adapted this framework slightly to best fit within their village. Although one of the strengths was having a stable organizational structure, some villages struggled finding reliable human resources (e.g. LHTs, recreation coordinator, arena manager, volunteers) to successfully implement the programme.

One recurring challenge was to find LHTs who were willing to commit to regularly run practices at the recreational level. Coordinator 1 stated: “Half the time kids will come to the rink and there’s no coach to run the practice…it’s pretty frustrating for the kids.” Although this was not the case for all LHTs it was a common theme, as Principal 2 explained: “He [youth LHT] is reliable, he goes every night. So for us, that’s a big step because other kids his age that are also LHTs, they are hit or miss 50% of the time—sometimes they show, sometimes they don’t.” Two stakeholders seconded this: “It’s hard to find members from the community that are really involved in the programme and that will stay for a while” (Coach 1) and “I want more local people helping out, helping the little people in the dressing room and on the ice…more LHTs on the ice for the younger kids. Parents should help.” (Youth 2)

Another identified challenge related to human resources was securing positions to support programme delivery at the recreational level, such as hockey coordinators, arena managers, and ice resurfacers. These positions extend beyond the NYHDP’s control, but still had an impact on the programme. The programme often struggled at the recreational level because several villages did not have regular arena operating hours or the arena and ice surface was not maintained. As Coach 2 discussed: “They wanted an arena manager, janitor, and security guard, but the municipality said we can’t afford that. [Adults] clean the ice for themselves at night, nevermind kids. There are always places, like in [village], no one takes care of the arena.” Coach 3 discussed the issue of consistency with staff at the local level: “For the most part you get someone great and you lose them; there’s many issues that even having regular hockey seems to be difficult with not having an arena manager”.

A desire for more parental involvement within the programme was also identified by stakeholders. Although there are many parents who support the overall goals of the programme, there was a lack of parental involvement within the program. It was identified from 2 years of community reports that no villages had parents who went on ice during practices, despite efforts made by NYHDP stakeholders to encourage this. Parent 1, who had two children participating in the programme spoke to this:

In the beginning, parents were getting involved, but as usual they slowly disappear, but there are always those few parents who always go and watches and supports, but I think we really need to support more. To make it really work, make it better, the LHTs need support from the parents.

Coach 2 discussed a possible cultural link as to why few parents are involved in the programme: “For a lot of parents the role of being a parent is to bring food on the table and have a place where kids can sleep. So if this is your perception of a parent, you’re far from going on the ice to support your kids learning hockey.”

Difficulties in maintaining formal partnership with the school board. As mentioned, a formal partnership between the NYHDP and the school board was eliminated in 2012 despite the intended goal of involving the school board as a key programme stakeholder. The partnership was eliminated as parties experienced difficulties reaching common ground for two reasons: differing rules and regulations of each organization and a lack of consistent implementation of NYHDP objectives across the village schools. Since this was not consistently carried out across the region, the partnership was formally eliminated. Programme adjustments have been made since the termination of the partnership. Although the programme was adapted based on this change, stakeholders shared mixed opinions on whether this decision was positive or negative for the programme. Principal 1 discussed how the lack of partnership meant youth may not be as motivated to attend school:

When we look at the grade fives and sixes and their hockey boys, we know they have a lot of baggage from home and for them to have hockey—they’re driven by hockey—it’s a sport they love. If I can use hockey as a reward for improvement in school then it means a lot to me as a school principal – if I can’t then there may be a problem.

A teacher-coach discussed his perspective:

It’s like if you play hockey in the south, no one asks you for your report card; it’s the same thing here right now. Last year, we had a bargaining tool. It kept a lot of kids in school. Now it’s a free-for-all. Which isn’t bad, it’s an extra-curricular, kids should be privy to that, but we lost that bargaining tool. (Coach 1)

Coach 2 went on to say:

I would say last year it kept a lot of kids coming more often—it’s not that those kids have dropped out, but it’s more ‘if I don’t show up to these two classes today, I’m not going to lose my hockey tonight so I’ll skip these two classes’, whereas last year, if you skipped you wouldn’t go to hockey that night.

In contrast, Youth 1 talked about how the elimination of the partnership provided opportunities to youth who might not have otherwise had a chance to play hockey: “For the kids that don’t go to school [consistently], it gives them something to do, like a chance. It’s probably not their fault that they’re not going to school because there are social problems so it gives them a chance.” A local coach seconded this when discussing the increase in participation rates since the end of the formal partnership: “There are more kids since the programme is not link directly with school so according to me it’s a good thing for the programme.” (January 12)

The decision to end the formal partnership was a result of inconsistencies in the implementation of the NYHDP policies. Principal 2 talked about how some teachers were using the programme partnership inappropriately: “I think one of the biggest problems is not having a supportive team under you as a principal; just a lot of teachers are not on board with the partnership or they use [hockey] in the opposite way—that it’s a punishment.” Similarly, Parent 2 explained that she had mixed emotions related to the partnership, as she believed there was potential for a successful partnership, yet was not implemented appropriately:

I think it really helped when it (hockey) was tied to school as long as it’s used right. There are students who struggle and I find they’re not being understood; they have more going on in their lives than people realize. [Teachers] use hockey as a punishment; the kids are struggling in life so they do bad behaviour and get punished and aren’t allowed to do what they love most (hockey). We need to figure out a way to use it properly.

Parent 1 believed that the decision to end the partnership was premature: “I find it’s too soon to let this programme go out of the schools because it was just starting and it needs to be there for years for the school to really understand how it works. It wasn’t there long enough to make a really strong impact.” It should be noted that some of the communities continued to implement policies that link participation to education despite the elimination of the formal partnership between the school board and NYHDP. For example, Principal 1 explained:

I meet parents of students who are underachieving. Most parents are at a loss as how to rectify the problem behaviour. For years, I have been hearing parents say, “My child doesn’t listen to me; my child listens better to you.” This year I have been hearing a new one: “Just cut their hockey.” It’s funny, but true—parents are begging me to cut their child’s hockey if they don’t attend school. Many parents appreciated that in the past we could use hockey to motivate their child to stay in school—they realize that success in school was a goal even more important than hockey.

This was further outlined in the ‘NYHDP had a positive impact on the region’ theme.

The NYHDP was expensive to implement. The NYHDP was identified as a costly programme primarily because of the geographical set-up of Nunavik and the transportation costs required to make the programme function. The competitive component and regional tournaments were the most expensive programme elements as youth were flown from their respective villages for tryouts, training camps, and tournaments. For example, in the 2012-2013 season competitive tryouts had 50 to 65 youth and regional tournaments has approximately 100 youth in attendance, which meant all youth who were not from the host village were flown to and from this location. Coach 4 discussed: “The price of plane tickets are really expensive from coast to coast so that’s a main issue…every year it’s a lot of money – it’s really expensive to travel in this area.” A charter was needed for each competitive team to travel to large cities in Ontario and Québec for the end-of-season tournament. Along with the costs for youth travel, there were also travel costs associated with stakeholders for programme implementation (e.g. coaches, coordinators). Additionally, it was noted that hockey was expensive to play and many youth from families living on low incomes could not afford the equipment. The Director noted: “Although hockey equipment availabilities are not always there for kids in all villages, we still see the numbers of participants grow, but equipment needs will continue to be a definite obstacle to allow more children to participate.” However, it was suggested that youth experiences and outcomes exceed the expense, as Coach 1 stated: “I know it’s really expensive, but it’s really fun…the kids go wild every time they go on the ice. It just gives a reason for the kids to play and practice.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore stakeholders’ perspectives of ongoing successes and challenges of implementing the NYHDP using a utilization-focused formative evaluation process. Results from this study indicate that successfully implementing a SFD programme in a northern, remote region requires many elements including having a well-planned, well-implemented programme framework, a stable organizational structure, and opportunities to increase local appropriation (leadership and coaching opportunities). These elements have helped facilitate increasing participation rates and positive perceptions regarding the programme impact on the region. While the NYHDP has been running for several years illustrating substantial growth and progress, challenges exist including the necessity for more reliable human resources within the programme, the decision to end the partnership with the school board, and the large expense involved in programme implementation. There is still much to be learned and adaptions to be made in order to improve the delivery of the programme to better meet the needs of participants while ensuring programme sustainability.

The capability of organizations to deliver effective sport programmes with individual and community development outcomes is influenced by internal and external organizational factors.6,7 The study reinforces this as internal (e.g. organizational structure, staff training) and external factors (e.g. availability of resources, partnerships) have a large impact on programme outcomes and sustainability. Further, researchers indicated that programme coordinators have pivotal roles in programme initiation, development, and maintenance throughout a programme’s lifetime29, which has been crucial within the NYHDP. Moreover, Child and Faulker30 identified coordinators are often involved in partner recruitment and training, communication with all stakeholders, programme promotion, and budgeting, which also holds true within the NYHDP. However, while there is one critical director, a core staff team was established over the past years, allowing for delegation and facilitation of local ownership. Fostering such ownership has been known to help reinforce programme sustainability and assist in long-term programme survival.31,32

Within this organizational structure, communication has been identified as a critical element in successful programmes, which in this study positively impacted the programme framework particularly at the competitive level. Researchers have discussed the importance of internal (e.g. between partners) and external (e.g. to parents and youth) communication.112,29 Moreover, researchers have also discussed how success of any development-oriented, sport-based programme is dependent upon many types of organizational and human resources, including communication amongst the various stakeholders involved.14,15 Therefore, the development of a core staff team as well as quality communication and training enabled opportunities to increase local appropriation such as leadership and coaching within the NYHDP. From this, there was an increase in Aboriginal coaches and LHTs, which not only allowed for easier communication, but also aided programme sustainability and allowed for the director to take on a facilitator role.

Previous research has indicated that Aboriginal youth have vocalized the desire for organized sport participation opportunities.3,17 Findings from this study outline that within Nunanvik, hockey has been successful in creating this opportunity based on increased participation rates over seven years. Moreover, hockey has not only been identified as of great cultural significance to Canadian Aboriginal populations,1 but also by other SFD programmes in Canada as an important vehicle for Aboriginal youth participants.39 Sport has been effective in keeping Aboriginal youth out of trouble5,6, which may be a consequence of NYHDP participation as stakeholders perceived hockey as a positive engagement opportunity for youth to be physically active, have fun, interact with peers and adults, and in some cases remain engaged at school.

While the partnership with the regional school board was identified as a challenge, this shift in the NYHDP allowed for the development of its own curriculum at both the competitive level through establishing a proactive approach that focuses on life skill development (effort, perseverance, teamwork) and recreationally through passing local resolutions. The elimination of the partnership modified NYHDP’s participation criteria, as participation was not linked to school reports. Previously, youth who were most at-risk and may not have been eligible to participate in the NYHDP based on criteria, such as poor school reports, were now given the opportunity to participate, yet education is still greatly encouraged. This allowed the opportunity for NYHDP stakeholders to closely work with these youth and provide a positive environment to participate in sport and work on fostering life skills.

A major component of the facilitation of SFD programmes is the lasting impacts they have on the community.33 The results of this study revealed that the implementation of the NYHDP led to significant infrastructure changes as arena improvements and purchase of equipment that was perceived as being able to aid the overall region outside of the programme itself and for a long time. Furthermore, the LHT programme component was perceived as enabling opportunities for more trained youth in the region to act as coaches at the local level, which has helped with capacity building, programme sustainability, and additional job opportunities for youth to be in a leadership role in a sport that they enjoy. Blodgett and colleagues34 discussed the importance of Aboriginal role models working towards the same purpose—youth development—enabling the potential for a better future and programme sustainability, as was identified as a critical success within the NYHDP, yet also an area to continue to improve upon.

Practical Recommendations

This study used a utilization-focused evaluation approach,which recognizes the important stakeholders who see benefit in using evaluation findings for future decision-making regarding the programme.18 The results of this study were disseminated to not only NYHDP stakeholders (e.g. executive committee, school board, regional government, funding organizations) through a written report, but also to the region by way of regional newsletter. Currently the stakeholders are working together to adapt the programme goals to better meet the programme participants’ needs and work towards programme improvement. As noted above, results from this study indicated that while there has been much progress in increasing local appropriation, a need still remains for consistent, reliable, and trained human resources at the recreational level for programme sustainability. While gains have been made at the local level over the past few years (e.g. increase in LHTs), the continuation of LHT and coach recruitment that are provided with in-depth training will allow for local capacity-building and enable more community appropriation within each village. Therefore, it is important to contextualize the programme within each village, as it has been noted that a “one-size-fits-all approach will not meet all community and individual needs.”17 It was recommended that the NYHDP work with each municipality to recruit and train arena staff and recreation coordinators to ensure that the arena is regularly maintained. Thus, trained LHTs will have opportunities to facilitate the local hockey programme while having additional human resources to work with them.

While Durlak and Dupree argued that programme adaptations should be related to peripheral and not central programme components;35 it was evident from this research that a central programme component, the school board partnership, was not working successfully. Therefore, a decision was made to terminate this partnership. Throughout the study, researchers worked with the organization and made plans to further improve the NYHDP by incorporating life skills activities as a core programme component. As an organization, it was important to recognize challenges within programme delivery and between partnerships and make changes that strengthen the programme, moving further towards programme sustainability. It was also important to use lessons learned from the challenges associated with the partnership with the school board in case this partnership were to be reinstated. Such lessons illustrate that a more formal training process would be needed to ensure that all involved stakeholders understand the purpose and expectations of the partnership.

It should also be noted that flexibility is critical when facilitating youth development programmes,36 but even more so is the importance of being flexible when working with Inuit cultures to ensure the programme goals are in line with the culture and are adaptable to the villages’ particular needs and goals.37 Since this programme is delivered in 14 different villages, it is critical to contextualize the programme to each individual village because each community has different needs and resources that can be specifically utilized to ensure high quality programming. Therefore, stakeholders are working with villages at the individual level to understand how to best facilitate the programme with the resources available.

One strategy for increasing this effectiveness and ultimately the sustainability of SFD programmes is collaborating with multiple partners that support programme goals and outcomes, assist with delivery, and provide funding.17 The United Nations33 also recognized this notion by highlighting that such partnerships can facilitate the leveraging of resources, including financial, human, and physical, as well as expertise, training, facilities, and equipment. The NYHDP continues to seek out new partners and has had success in this area. Since this study, funding was attained from the Canadian Tire Jump Start Foundation, which will go towards hockey equipment to maximize programme participation. CBC profiled the NYHDP during CBC’s Hockey Day in Canada in the winter of 2015, garnering much media attention.

Finally, the results of this study indicated that parents are a crucial element to the programme, yet only a small percentage of parents are involved. This is consistent with findings from other studies within the Aboriginal youth sport context.34 The finding could be explained by the work of Arsenault38 who found that parents perceived their role within a family in Nunavik as one that should focus on providing basic necessities such as food and shelter as opposed to engagement in leisure activities. Moving forward, it would be important to find ways to further engage parents, such as offering youth-parent games.

Limitations

Although this study provides an understanding of the NYHDP processes, it is not without limitations. First and foremost, it is important to recognize the potential bias of this study with the potential of utilizing a Westernized evaluation approach. Although such an approach was used, the study was participatory and involved stakeholders’ perspectives; however, future research can be done to develop and use an Indigenous approach to evaluation. Moreover, future research should include more youth in the evaluation process, since they are the targeted population. Third, interviews were conducted with stakeholders who tended to show an interest and/or were involved in the programme and may have a positive bias towards programme operations. Although recruitment of stakeholders not involved in the NYHDP was attempted, they were not interested in participating in the study. In the future, it would be beneficial to document the perceptions of stakeholders not involved in the programme to better understand the motives behind the lack of involvement. Additionally, there is potential for self-monitoring when participants are aware of programme evaluations. Lastly, data were based on self-reported perceptions through interviews; however programme documents and researchers’ on-site experiences did help to verify findings.

Conclusion

This study represents one of the first utilization-focused programme evaluations conducted of a SFD programme within a Canadian Aboriginal context. Results from this paper show that a well-structured programme that has a stable organizational structure and uses local human resources for implementation and sustainability is perceived as having a positive impact on both the region in which it is implemented and among the participants involved. Moving forward, it is critical to understand how to modify and further develop the programme based on ongoing challenges. Therefore, continuing to recruit reliable human resources and finding a way to best connect a sport-based programs to other systems within the community such as the schools to further integrate the importance of education is important. While there is still much to be learned and adaptions to be made in order to improve the delivery of the programme to better meet the needs of participants and ensure programme sustainability, results from this study have aided in the improvement of the NYHDP. The results may also act as a catalyst for expanding the programme to more participants and can possibly provide a strong framework for other Aboriginal populations interested in implementing a youth SFD programme.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their involvement in this study, as well as the Nunavik Youth Hockey Development Program for their collaboration and ongoing support throughout this project.

References

1. Robidoux MA. Stickhandling Through the Margins: First Nations Hockey in Canada: University of Toronto Press; 2012.

2. Library and Archives Canada. Aboriginal hockey 2010 [10 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/hockey/024002-2401-e.html.

3. Mohajer N, Bessarab D, Earnest J. There should be more help out here! A qualitative study of the needs of Aboriginal adolescents in rural Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(1137);1-11.

4. Skinner K, Hanning RM, Tsuji LJ. Barriers and supports for healthy eating and physical activity for First Nation youths in northern Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2006;65(2).

5. Tatz C. Aborigines: Sport, violence and survival. A report to the Criminology Research Council. Macquarie University, N.S.W.: 1994.

6. Mulholland E. What sport can do: The True Sport report. 2008.

7. Hanna R. Promoting, developing, and sustaining sports, recreation, and physical activity in British Columbia for Aboriginal youth. Document created for First Nations Health Society [online] Available from:[Accessed 15 April 2013]. 2009.

8. Nunavik Youth Hockey Development Program. Encouraging and educating youth through hockey 2010 [2 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nyhdp.ca/.

9. CAPTURE. Sage Advice: Real-world approaches to program evaluation in northern, remote and Aboriginal communities 2010 [16 November 2014]. Available from: http://reciprocalconsulting.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Sage-Advice-English.pdf.

10. Halsall T, Forneris T. Evaluation of the Promoting Life-skills in Aboriginal Youth (PLAY) program: Stories of positive youth development and community development. Appl Dev Sci. submitted 2015:31.

11. Blodgett AT, Schinke RJ, Fisher LA, Yungblut HE, Recollet‐Saikkonen D, Peltier D, et al. Praxis and community‐level sport programming strategies in a Canadian Aboriginal reserve. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2010;8(3):262-83.

12. Coalter F. The politics of sport-for-development: limited focus programmes and broad gauge problems? Int Rev Sociol Sport. 2010;45(3):295-314.

13. Kidd B. A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport in Society. 2008;11(4):370-80.

14. MacIntosh E, Spence K. An exploration of stakeholder values: In search of common ground within an international sport and development initiative. Sport Man Rev. 2012;15(4):404-15.

15. Willis O. Sport and development: the significance of Mathare Youth Sports Association. Canadian J Devel Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement. 2000;21(3):825-49.

16. Burnett C. Engaging sport-for-development for social impact in the South African context. Sport in society. 2009;12(9):1192-205.

17. Skinner J, Zakus DH, Cowell J. Development through sport: Building social capital in disadvantaged communities. Sport Man Rev. 2008;11(3):253-75.

18. Patton MQ. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry a personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work. 2002;1(3):261-83.

19. Patton MQ. Utilization-focused evaluation: Springer; 2000.

20. Epps SE, Jackson BJ. Empowered families, successful children: Early intervention programs that work: American Psychological Association; 2000.

21. Weiss CH. Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluation? Am J Eval. 1998;19(1):21-33.

22. Armstrong LL. A utilization-focused approach to evaluating a “youth-friendly” mental health program: The Youth Net/Réseau Ado story. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2009;4(4):361-9.

23. Bean CN, Kendellen K, Halsall T, Forneris T. Putting program evaluation into practice: Enhancing the Girls Just Wanna Have Fun program. Eval Program Plann. 2014; 49:31-40.

24. Flowers AB. Blazing an evaluation pathway: Lessons learned from applying utilization-focused evaluation to a conservation education program. Eval Program Plann. 2010;33(2):165-71.

25. Coalter F. A wider social role for sport: who’s keeping the score?: Taylor & Francis; 2007.

26. Maxwell JA. Causal explanation, qualitative research, and scientific inquiry in education. Educational Researcher. 2004;33(2):3-11.

27. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.

28. Makivik Corporation. Nunavik maps 2015 [7 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.makivik.org/nunavik-maps/.

29. Parent M, Harvey J. Partnership management of children’s community-based sport programs: A model and lessons drawn from Kids in Shape. 2013.

30. Child J, Faulkner D. Strategies of cooperation: Managing alliances, networks, and joint ventures. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

31. Rowley KG, Daniel M, Skinner K, Skinner M, White GA, O’Dea K. Effectiveness of a community‐directed ‘healthy lifestyle’program in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(2):136-44.

32. Varghese J, Krogman NT, Beckley TM, Nadeau S. Critical analysis of the relationship between local ownership and community resiliency. Rural Sociol. 2006;71(3):505-27.

33. United Nations. Harnessing the power of sport for deveopment and peace: Recommendations to governments. 2005.

34. Blodgett AT, Schinke RJ, Fisher LA, George CW, Peltier D, Ritchie S, et al. From practice to praxis community-based strategies for Aboriginal youth sport. J Sport & Social Issues. 2008;32(4):393-414.

35. Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):327-50.

36. Ward S, Parker M. The voice of youth: atmosphere in positive youth development program. Phys Edu Sport Pedagogy. 2013;18(5):534-48.

37. Castleden H, Garvin T, Nation H-a-aF. “Hishuk Tsawak”(everything is one/connected): a Huu-ay-aht worldview for seeing forestry in British Columbia, Canada. Soc Na Resour. 2009;22(9):789-804.

38. Arsenault MP. Assessment of parental involvement in the NYHDP Presented to Makivik Corporation and Nunavik Youth Hockey Development Program.: 2011.