Rochelle Stewart-Withers1, Jeremy Hapeta1

1 Massey University, New Zealand

Citation:

Stewart-Withers, R. & Hapeta, J. (2020). An examination of an Aotearoa/New Zealand plus-sport education partnership using livelihoods and capital analysis. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Education is regarded as a human right and fundamental to achieving other human rights, such as decent work. Education is essential for developing human potential, and it can help address growing social and economic inequality. However, for many Indigenous populations in the global North, realizing their fullest potential thorough mainstream education is mired with difficulties, and this has had serious implications for employability and livelihoods creation. This paper presents research undertaken in Aotearoa/New Zealand (NZ) where the Taranaki Rugby Football Union (TRFU) has partnered with local education provider Feats to establish the Māori and Pasifika Rugby Academy (MPRA). The purpose of the partnership is to provide an alternative education pathway to increase livelihoods opportunities. Undertaking a capital and livelihoods analysis of the TRFU and Feats partnership has allowed us to see more clearly different aspects of the MPRA program and bring to the fore other features of the learners’ journeys. While the building of human capital through education is important, of greater significance is the cultural and psychological capital that is built through program attendance.

INTRODUCTION

Livelihood theory and practice, referred to as the sustainable livelihoods approach or framework, emerged from the global-South rural and agricultural sector (Scoones, 2009). Its genealogy lies in influences such as the applied development perspective of Chambers (1995) and his advocating “putting the last first.” By this, Chambers (1995) was referring to the idea that development “experts” needed to listen to and include the voices, ideas, and experiences of disadvantaged people and start working in a bottom-up, participatory manner if poverty and underdevelopment were to be addressed. Other influences included work undertaken by French social scientist Pierre Bourdieu (1977) and rural sociologist Norman Long (2001), both of whom wrote about the need to understand the local environment within which development interventions and processes occur. Bourdieu (1977), and later, Long (2001) stressed the importance of understanding forms of capital, agency, and the capabilities of local actors within the constraints of broader national and global forces (markets and social policies, for example). Such a perspective was posited to offer a better means for capturing how vulnerable populations lived their lives and for obtaining a more nuanced understanding of the various things they did in order to make a living (Chambers & Conway, 1992). This interest in understanding peoples livelihoods in more detail has resulted in a growing body of scholarship focused on livelihoods analysis.

Key to livelihoods analysis is the idea that livelihoods in themselves are only useful if they can be sustained (Chambers & Conway, 1992). Sustainability encompasses the present as well as future generations. As an approach, it looks to include all dimensions of work, paid and unpaid (because not all work is paid), as well as formal and informal work (Snyder, 2007). By accounting for the informal sector, it recognizes that the majority of people in the global South are excluded from formal labor markets and receive little support from the state (Jeanes et al., 2019). While in the global North there might be social services, for those unemployed or in low skilled, short-term, casual, or poorly paid jobs, insurance, nutritious food, and quality housing and health care are often out of reach. Vulnerable populations face many uncertainties in their daily lives. Livelihoods analysis therefore looks to link macrolevel processes, such as, economic reform, to microlevel outcomes and responses.

Livelihoods scholars argue people are more likely to have good livelihood options when they have various kinds of capital to draw on (Chambers, 1995). The commonly identified types of capital are: human, financial, social, cultural, physical, and natural capital (Chambers & Conway, 1992). Natural capital, in some instances, has been replaced by personal capital (see Murray & Ferguson, 2002). Other forms of capital have also been discussed: aspirational, psychological, productive, and political, for example (see Moser et al., 2001). While this paper will focus on some capital types more than others, this is not to negate the importance of other forms of capital. Rather, in keeping with livelihoods analysis, context determines which capital types are most relevant, i.e., for a person living in an urban environment, natural capital is often less important than for a person living a rural life who is dependent on agriculture (UNODC, 2011).

Livelihoods analysis is interested in understanding peoples’ capabilities and what things limit people’s capabilities when trying to make a living. Also of interest is understanding how resilient people are, that is, how people respond to change and cope with stresses and shocks within their livelihood’s context. Communities, households, and individuals are seen to be resilient when they can grow their capital (Chambers, 1995; Chambers & Conway, 1992). While it is recognized that poorer communities, households, and individuals face greater challenges, making building resiliency vital, livelihoods analysis looks to position those who are disadvantaged as active agents of change rather than victims (Chambers, 1995; Chambers & Conway, 1992). Thus, resiliency can be developed.

There are many ways that sport directly contributes to people’s livelihoods—as an athlete, coach, sport administrator, manager, or sport physiotherapist. The scale of the global sports industry and its links with other sectors such as tourism, health care, or hospitality offers prospects for employment as well (SDGFund, 2018). Opportunities also occur when sport-labor migrants remit money home and family members set up income generating ventures (Stewart-Withers et al., 2017), or when sport-based initiatives look to target at-risk populations with the intention of developing employment skills (Sherry, 2017). Employability skills have been defined as hard skills or those that relate specifically to the job at hand, and soft skills “are personal attitudinal and behavioural attributes” (Coalter et al., 2016, p.12).

With this in mind, this paper presents a livelihoods analysis drawing on research undertaken in Aotearoa/New Zealand (NZ)1, where the Taranaki Rugby Football Union (TRFU) partnered with local education provider Feats, or Pae Tawhiti (to “seek out distant horizons”) to establish the Māori and Pasifika Rugby Academy (MPRA). Feats offers MPRA participants the opportunity to obtain National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA2) Levels 1 and 2, which are delivered through Pasifika and Māori tikanga (protocols; ways of knowing, doing, and being) incorporating hauora (well-being), whānau (family) support, all with a focus on sport (rugby union) and physical fitness (Burroughs, 2016). The rationale for shining light on this “particularistic” case (Merriam, 1998), albeit small, is because this partnership is unique insofar as it privileges educational achievement within a culturally responsive environment, and the sport itself has a secondary focus. In positioning sport as a secondary focus, it provides a counter to other popular sport academy models or programs in Aotearoa. Brown (2015, 2016, 2017) has critiqued some of these popular programs, labelling them as “elite athlete programs” (EAPs), and positing that sporting successes come first and other outcomes, whether educational or sociocultural, are secondary. The TRFU and Feats partnership, with its education-focused MPRA, is a plus-sport approach (Coalter & Taylor, 2010) in which education intersects with rugby union to provide an alternative pathway for obtaining formal educational qualifications.

For this paper, because we were interested in extrapolating the capital aspect of livelihoods, we have posed five capital focused research questions:

- What types of capital do learners3 possess on entering the MPRA/Feats program?

- How does involvement in the MPRA/Feats program help learners grow capital?

- What are the dominant capital types that are grown?

- How do the types of capital help learners respond to change and cope with challenges and stresses?

- How do the types of capital contribute to creating choices and opportunities for the future, whereby learners in this MPRA/Feats program are able improve their livelihoods options?

This paper is structured first to unpack some of the arguments surrounding education as a means for building capital. Of concern is the way human capital has often been privileged over other capital categories, such as cultural capital. Second, we provide important contextual information. As will be evidenced, Aotearoa’s Indigenous people (Māori) as well as Pasifika peoples, have long experienced shortcomings in mainstream education that have implications for employment and livelihoods opportunities. For this reason, initiatives such as the MPRA and partnerships such as that with TRFU/Feats are important. These locally responsive solutions can resonate with Māori and Pasifika young men, especially, due to the ways various forms of rugby (union, league, touch, and sevens) are embraced by these groups from an early age (Horton, 2012). Following an outline of ethics, methodology, methods of data collection and analysis, we then present the findings according to the types of capital. Findings are discussed in relation to our research questions and in terms of livelihoods and capital analysis. In this education-focused exploratory case study, cultural and psychological capital are key to making the most of other forms of capital and are necessary for increased capabilities and improved livelihoods outcomes.

BACKGROUND

Education As Means for Building Capital

Education is seen as a means to increase human capital. According to the World Bank (2017)4, “human capital consists of the knowledge, skills and health that people accumulate throughout their lives, enabling them to realize their potential and be productive members of society.” Economists made the concept of human capital popular in the 1950s, with expenditure on education and training seen as an investment in human capital. However, using education as a means for producing workers who contribute to GDP as instruments for economic progress has been heavily criticized. Rather, education is “both a human right in itself and an indispensable means of realising other human rights. Education is essential for the development of human potential, enjoyment of the full range of human rights and respect for the rights of others” (Human Rights Commission, 2019, p.169). As evidenced by key New Zealand government policy documents and action plans, for example, “Shaping a Stronger Education System with New Zealanders,” and notwithstanding the fact Aotearoa is also a signatory to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals5, there appears to be a commitment to the idea that education is a fundamental human right for all (Human Rights Act, 1993). Education is hence positioned as part of the broader development agenda.

Education has long been part of the development agenda as Millennium Development Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education. Problematically, the focus was mainly on enrollment and attendance in formal education, as opposed to the quality of this education (Barrett, 2015). The wider scope of SDG 4 – Quality Education6 and the focus on inclusiveness and equity looks to address this. Thus, seven targets and 11 indictors for SDG 4 were agreed to by 193 countries in September 2015 at the United Nations and look to, for example, improve proficiency in numeracy and literacy and ensure equal access to affordable and quality technical, vocational, and tertiary education, especially for youth, Indigenous people, and other marginal groups. It is noted that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to live sustainable lives, thus realizing their rights as citizens. Recognition of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to development is also very important (UN, 2016).

Within Aotearoa’s formal education system, different subjects tend to value the inclusion of culture more than others. Review and Maintenance Programme (RAMP) reports of Health and Physical Education (HPE) (Boyd & Hipkins, 2015), Mathematics and Statistics (Neill & Hipkins, 2015), and Science (Hipkins & Joyce, 2015), illustrate there to be a much stronger “culturally responsive pedagogy” within HPE. Boyd and Hipkins (2015) attribute this to the explicit use of hauora, an Indigenous holistic model of well-being (Durie, 1994), as one of the four concepts that underpin learning in HPE. We argue that including diverse cultural perspectives including Indigenous models and understandings of the subject area (in this instance health and well-being) as well as experiences that connect with the interests of learners and their communities is very important.

In view of the background of the paper presented above and moving forward with the case study, a livelihoods and capital analysis of SFD employability programs argues the importance of these specific tenets:

- working from a plus-sport perspective and valuing partnerships;

- targeting not just hard skills but also soft skills;

- working in a bottom-up, participatory manner;

- listening to and responding to the voices, ideas, and experiences of participants;

- understanding and working with the local environment;

- looking to understand capital—context determines which forms of capital are most relevant;

- exploring how resilient participants think they are, in terms of responding to change, coping with stresses, and growing their capital;

- looking to understand participants’ capabilities and what things limit their capabilities with respects to capital; and

- positioning participants as active agents of change rather than victims.

Case Study: The Māori and Pasifika Rugby Academy (MPRA)

Brief Introduction to Māori and Pasifika People in Aotearoa

This study focuses on Māori (the Indigenous people of Aotearoa) and is the modern-day term used to refer to tangata whenua (the people of the land). Māori arrived in Aotearoa in ocean-going vessels (waka) from east Polynesia during the 13th century (Statistics NZ, 2015). In 1642, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to visit Aotearoa. Over a century later, in 1769, the English navigator James Cook mapped the country’s coastal area. Almost three quarters of a century later, on February 6, 1840, over 500 Māori chiefs signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi) on behalf of their people and representatives of Queen Victoria’s British Crown. Thus, Aotearoa became an official British colony in 1840 (McLeod et al., 2011). Many new settlers arrived, mainly from the United Kingdom, and they soon outnumbered the Māori population. The newly instated government broke treaty promises protecting Māori rights, and over the years that followed, the impacts of colonization, assimilation, and marginalization had enormous negative impacts on the social, economic, and cultural well-being of Māori (Statistics NZ, 2015). Since 1975, the Aotearoa government has negotiated settlements with Māori to address breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and improve the situation and position of the Indigenous population.

The 2013 Census reports that 15.7% of Aotearoa’s population are of Māori descent, but fewer (13.4%) self-identified as Māori, and more than half of these identified with two or more ethnic groups (Statistics NZ, 2013). Cultural identity for Māori is, therefore, complex. As of 2015, an estimated 51% of the Māori population were 24 years of age or younger (Statistics NZ, 2015)—an important statistic given the focus of this article is youth. With reference to Pasifika peoples, the phrase “Pacific people” refers to a diverse group of people living in Aotearoa who migrated from Polynesia, Micronesian, or Melanesia, or who identify with the Pacific Islands because of ancestry or heritage. Many Pacific people migrated to Aotearoa for a better livelihood and/or to earn money for their families back home, and subsequently they have become a permanent and significant group on the Aotearoa landscape. In 2013, about 7.4% of Aotearoa’s population were of Pacific descent (Statistics NZ, 2013). Similar for Māori, Pacific peoples also face discrimination and marginalization and experience varying levels of inequality in terms of opportunity and social and economic outcomes comparative to Pākehā (people of European decent), especially in the formal education system (Hunter et al., 2016; Milne, 2010, 2016).

Education for Māori and Pacific Youth

From 2009-2018, educational improvements were recorded for all ethnic groups. However, in terms of the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) figures, all groups have consistently improved, therefore, the “gap” between high- and low-level achievers remains. Three in every four (75.7%) individuals of Asian descent leaving school, for example, achieved NCEA Level 3 or above in 2018, which is 19.3% higher than second- place European/Pākehā (56.4%) students. Less than one in every two Pasifika individuals leaving school achieved NCEA level 3 (46.1%), and for Māori only one in three (or 35.3%) left with NCEA Level 3. Across all individuals leaving school between 2009 and 2018, the Pasifika group, for example, recorded the largest improvement (22.9%) followed by Māori with a 16.2% increase between 2009 and 2018. Asian (12%) and European/Pākehā (9.2%) individuals leaving school also experienced respective gains between 2009-2018. There are myriad reasons for these ongoing structural disparities (inequalities outside the scope of this article), but beyond HPE, more “traditional” learning areas do not appear to cater to culturally diverse perspectives (Boyd & Hipkins, 2015; Hunter et al., 2016).

METHODS

Ethics

This project was peer reviewed and deemed low risk, and notification was lodged with the university’s Human Ethics Office. This project is also underpinned by various culturally informed ethical principles, as seen in the NZ Health Research Council’s Te Ara Tika document, where “mana—justice and equity,” “whakapapa—relationships,” “manaakitanga—cultural and social responsibility” and “tika—appropriateness of research design,” are all argued to be fundamental (Hudson et al., 2019). As well as Massey University’s Pacific Research Principles, where “respect for relationships,” “respect for knowledge holders,” reciprocity,” “holism,” and “using research to do good” are essential (Meo-Sewabu et al., 2017). In the example of reciprocity, what these meant in practical terms for the study was the importance of expressing gratitude to people for their time and service through sharing food, helping profile the organization, and returning to present our findings in an accessible way to those involved (see Meo-Sewabu et al., 2017 for a detailed account of these principles).

Participants: The Taranaki Māori and Pacific Rugby Academy (MPRA) and Feats

First, to give some background, Feats (Pae Tawhiti) was founded in March 1992 and achieved registration with the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) as a private training establishment in 1995 to administer and deliver training programs for youth and the unemployed. Typically, learners are referred to Feats either by government welfare agencies such as Work and Income or by local high schools when students have not been successful with their exams. A quarter century later, Feats now offers a range of programs on three campuses in the Taranaki region (Stratford, Hawera, and New Plymouth). These programs include: Training for Work, Keystones, NCEA, and the Maori and Pasifika Rugby Academy (MPRA).

The programs are run as timed sessions that resemble a traditional school day. Usually, learners begin their courses by 9 a.m. and finish at around 4 p.m. Monday to Friday at one of Feats’s three sites. Three programs focus on employability (Training for Work, where learners gain skills to become work ready) and education (Keystones—where learners’ specific needs are met in math, reading and/or writing), and NCEA. Their fourth program, which is the focus of this article (the MPRA), has an education “plus-sport” approach in which NCEA Levels 1 and 2 credits are delivered via a sport (rugby) academy that encompasses Pasifika values and Māori tikanga (protocols) incorporating hauora (holistic well-being), whanau (family) support, and physical fitness.

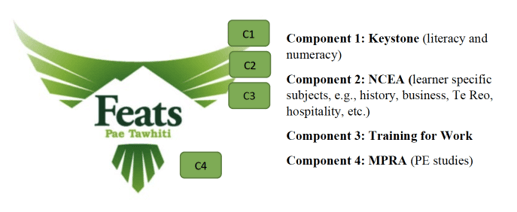

Second, the MPRA was the culmination of a year’s work between the Taranaki Rugby Football Union (TRFU) and their partners, Feats. From inception, the TRFU committed to use rugby as the carrot to attract youth to Feats in order to gain important qualifications, especially for Māori and Pasifika students who were underachieving within the mainstream education system (Burroughs, 2016). Additionally, alongside the aspirations of their learners gaining NCEA qualifications and rugby skills, the program also teaches students life skills by developing their understandings of tikanga Māori and Pasifika culture and customs (TRFU, 2019). Learners have access to no less than three dedicated staff members to cater to their needs, including a Feats facilitator, the TRFU Academy manager, and a TRFU strength and conditioning trainer. The MPRA learning components are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Structure of the various MRPA learning components

The MPRA case, therefore, may be considered a “plus-sport” education-focused initiative. It can be considered a “particularistic” case (Merriam, 1998) as, arguably, it operates contrary to other popular sport-only or sport-plus academy models.

Procedure

This qualitative, two-phased, inductive research (Gratton & Jones, 2004; Keegan et al., 2014) takes a case study approach, which, as Merriam (1998) suggests, is “an intensive, holistic description and analysis of a bounded phenomenon such as a program, an institution . . . or a social unit” (p. xiii). Thus alongside being particularistic, it is also descriptive and heuristic (Merriam, 1998). In keeping with Merriam’s (1998) pragmatism, it was important to “utilize processes that help interpret, sort, and manage information and that adapt findings to convey clarity and applicability to the results” (Harrison et al., 2017, para. 24).

Data Collection and Analysis

Our data collection across two phases allowed for inductive reasoning, by which researchers start with an observation or study of case incidents and then establish generalities. Sparkes and Smith (2013) refer to this as “a ‘bottom-up’ approach that is concerned with descriptions and explanations of particular phenomena or with developing theories” (p.25). In keeping with Merriam (1998), gathering data across these two phases allowed us to make links and connections and gave us time between the phases to develop working theories of the observed phenomena (MPRA).

The first phase of data collection for this research occurred mid-2018. The primary methods used to collect data were semistructured, focus group interviews with past learners (graduates) (n=4) from the 2017 intake (pseudonyms Tahi, Rua, Toru, and Wha7) and another focus group with course facilitators (n=4), including Feats and TRFU staff. Interview questions were open ended, and both focus groups occurred at their central Taranaki (Stratford) campus. Documents (strategic plans) were also collected. Observations were noted while on-site to complement the data gathered from the learners.

The second phase of data collection was in early 20198 with Feats facilitators9 (n=2) and MPRA learners (n=5) (pseudonyms Rima, Ono, Whitu, Waru, and Iwa)10 via open-ended, semistructured, individual interviews. These occurred at the New Plymouth campus. Again, the researchers collected documents (learner goal setting plans, n=13) and made observations while on-site to complement the interview data. While the focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the second author, the individual interviews were not recorded. Rather, the first author, drawing on first phase experience and using Merriam’s (1998) simultaneity of data collection and analysis approach, took detailed notes during the interviews. A further rationale for this was also that learners were more comfortable being recorded in a group setting compared to the one-on-one sessions.

Finally, qualitative content analysis involved “making sense out of the data . . . consolidating, reducing, and interpreting what people have said and what the researcher has seen and read—it is the process of making meaning” (Merriam, 1998, p. 178). All sources (focus group transcriptions, one-on-one interview notes, observation notes, and other documents) were reviewed in relation to the five capital focused research questions and with learners as agents of change. This strategy was employed after phase one, when both authors conducted independent content analysis of the verbatim transcribed audio recordings. This involved each researcher familiarizing themselves with the data set and re-examining the data, highlighting key initial thoughts. This was followed by phase two, in which the first author adopted simultaneous coding for themes by noting meaningful quotes (i.e., raw data). Together, themes from both data sets were organized into capital types reflecting their relationships with livelihoods. Thus, an inductive approach was used to extract themes in relation to capital types and livelihoods (Huysmans et al., 2019). Iterative consensus validation enabled the authors to compare initial thoughts, codes, and themes, along with achieving consensus and resolving discrepancies. Another researcher acted as a “critical friend,” whose primary role was to prompt reflection on alternative interpretations. On completion of the content analysis, all analyzed data was triangulated and integrated in a process of iterative consensus validation involving the researchers (Merriam, 1998).

The definitions of the types of capital are as follows:

- Human capital refers to the knowledge, skills, and health of people (World Bank, 2017).

- Psychological capital is often articulated in terms of H = hope, E = efficacy, R = resilience, and O = optimism (Luthans et al., 2007; Moser et al., 2001).

- Social capital consists of social resources, networks, organizations, and associations, both formal or informal, that occur or develop though relationships of trust that people draw from (Chambers, 1995; Chambers & Conway, 1992).

- Cultural capital is understood as existing as embodied (internalized values and ideas), objectified (material/tangible products), and institutionalized (social entitlements) forms (Bourdieu, 1986).

FINDINGS11

Human Capital

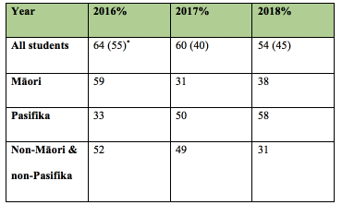

Given the MPRA’s education focus, the most evident capital developed was human capital. As an example of the knowledge-building aspect of human capital, one Feats facilitator commented, “Students come with low or no credits in NCEA, but this current group is 8 to 10 weeks away from completing . . . and are even ahead of schedule” (Feats facilitator, 2019). Human capital is thus grown in the form of achievement of formal academic qualifications, specifically NCEA Levels 1-2. Table 1 depicts completion and success rates for the program for 2016-2018.

Table 1 – Percent of learners completing the feats program by year, 2016-2018

Note – Adapted from New Zealand Qualifications Authority (2019, July 30). External evaluation and review report: Feats Ltd. p. 11 (http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/nqfdocs/provider-reports/8692.pdf).

*The NZ Tertiary Education Commission (TEC), which provides the funding for Feats, is committed to students getting NCEA Level 1 and 2 qualifications. Their targets for students completing qualifications are noted in parentheses.

By being involved in the MPRA, the learners have an increased ability to move into further training and education after Feats and/or paid employment. For example, one learner commented,

I’m working, I’m roofing at [X] roofers. I actually found their phone number on the internet and called them up, asked them if they were looking for workers and they said yeah. Then they gave me a month’s trial. So, I’m there full time now. (Tahi, learner, 2018)

I got accepted into work for fitness course personal training. I got a message the other day from the work tutors saying I’ve been accepted. So, I start next month. Something cool I can do . . . because I’ve got a lot of unfit people in my family too. (Toru, learner, 2018)

Human capital can be further seen by the fact that all learners came with a passion for and knowledge of rugby and other sports. While most of the learners did not have outstanding talent, elite sport development is not the intention of this plus-sport organization. Regardless of talent, all learners are interested in having a healthy body. One facilitator noted, “after three months using the gym, [the learners] are really competent and confident with their ability in the gym” (MPRA, facilitator, 2018). All learners we interviewed have a sense of pride being part of the MPRA, demonstrating increased self-worth and improved mental well-being, which speaks to the development of psychological capital.

Psychological Capital

Aligned with livelihoods strength-based thinking, the CEO of Feats stated learners are viewed for their inherent potential “of what they could become in the future, not defined by their past or why and how they ended up at Feats” (2018). Many learners arrive with a sense of hope and optimism that Feats will get them back on track. Two shared their experience:

School wasn’t going well [because] my attitude was shocking. I don’t swear anymore, there is no reason for it. I feel I’m on track now. I feel like I am getting a second chance in life. (Whitu, learner, 2019)

I was just too angry to go to school. Never wanted to go. So, I thought I’d come here, hang out with the boys I guess . . . get in a little bit of trouble. But that all changed when I came here. None of the boys wanted to get in trouble so I had to change, eh. (Toru, learner, 2018)

Ono is an example of a learner who already had NCEA Level 1 and was looking to progress to NCEA Level 2:

Ono has the potential to succeed in life if he can learn to stand on his own two feet. Ono has a constant need to follow others and can at times be easily influenced. Since joining I have seen a rapid change in Ono’s attitude. He’s committed to being here every day, he’s punctual, he asks questions and is willing to participate in activities. (Feats facilitator, 2019)

Additionally, learner Rua, after spending time at Feats, returned to mainstream schooling to give things another go:

Yeah, I’ve learned so much here that I’ve taken there. Because at school I was always scared to ask questions, but here I could just ask anything. I am trying to get an apprenticeship for building. (2018)

Within this type of learning environment, the many positive personal skills and attributes that learners most likely have, such as being a team player or having a sense of humor, become more apparent:

Rima hasn’t been with me long. However, he has shown he is capable of working in a team environment but at the same time works well individually. Rima is definitely a character. (Feats facilitator, 2019)

Social Capital

Young people who are not succeeding in school are often disconnected from support systems. For these learners, however, there was often still someone, whether it was a coach, teacher, neighbor, or family member, who tried to be supportive and wished for them to succeed. One of the learners mentioned his “Nan” taught him about respecting all people: “even though I didn’t learn [about respecting people in the past], but eventually I did” (Wha, learner, 2018).

The learners also all came possessing social connectedness, whether this was due to having a peer group, good friends, siblings who were like mates, or a connection via their mobile phones with apps such as Snapchat, Facebook Messenger, or Instagram. Some of the learners joined the program because they followed their social networks:

To be honest I only came on the course because school wasn’t really that much fun, eh! And all my mates came along, so I just joined along pretty much. (Wha, learner, 2018)

I just followed him! (Tahi, learner, 2018)

Cultural Capital

There can be overlaps between psychological, social, and cultural capital. The distinction between cultural and social capital can disappear in the Māori context. Robinson and Williams (2001) suggest, “Cultural capital is an important aspect of social capital and social capital is an expression of cultural capital in practice. Social capital is based on and grows from the norms, values, networks and ways of operating that are the core of cultural capital” (p. 55). A similar point has been made with reference to Pasifika people (Stewart-Withers & O’Brien, 2006). This said, it is important that cultural capital is not subsumed and conceptualized simply as a component of social capital. Due to the Aotearoa context and the MPRA case, cultural capital warrants treatment as a separate category (Dalziel et al., 2009).

There is a Māori whakataukī (proverb) that states: Inā kei te mohio koe ko wai koe, i anga mai koe i hea, kei te mohio koe. Kei te anga atu ki hea—If you know who you are and where you are from, then you will know where you are going. This was a feature of Feats and reaffirmed learners’ cultural identity (cultural capital) and their tūrangawaewae (place of belonging) (social capital). Participating in the MPRA clearly contributed to the development of cultural capital. For Māori and Pacific people, sharing their pepehā (personal narratives) is important, anchoring their cultural identity terrestrially with their tūrangawaewae (place of belonging) and celestially with their tupuna (ancestors) (Durie, 1999). Learners were encouraged to consider “who I am?” “who do I descend from?” “where do I come from?” and “where do I belong?”—prompts that are an implicit part of the pepehā process. Pepehā were shared in both Te Reo Māori and English by the non-Māori (Fijian and Kiribatian) youth, with varying degrees of confidence and competence observed:

I understand some of the customs and protocols much better now. I can give my pepehā. I feel better using reo, and when I say this to people it makes me feel proud to talk about who I am and where I come from. It helps me think about where I want to go and who I want to be. (Rima, learner, 2019)

In focusing on developing cultural capital, and thus the norms, values, and practices that shape identity, social interaction, and attachment to place, many learners looked to change the ways in which they behaved and interacted. In understanding the rules and norms of the MPRA and life according to tikanga (Māori protocols), they came to understand the importance of relationships and respect, and there was a desire to fit in and belong. This reflects back to the earlier point made by Toru about none of the boys wanting to get in trouble so having to change to fit in.

Overlapping of the Capital Types: Developing Soft Skills

We can see an overlap with psychological/social and cultural capital as feeling safe, having a sense of belonging, feeling valued and respected, and having pride in being Māori and/or Pasifika. Learner Toru stated,

We don’t get singled out [negatively] because we’re Māori, we don’t get singled out because we’re Pasifika. Here we’re all the same. It feels like were just a family to be honest. (2018)

In terms of attributes that are valuable beyond the program classroom, both learners and facilitators spoke about growth in confidence:

Tahi’s confidence has grown dramatically. I believe he can achieve anything in life he sets his mind to. (Feats facilitator, 2019)

I was always scared to ask questions to people like to others, but now because [X] told me don’t be scared, this is your home. These are your brothers and sisters. At school I’m sitting beside a palagi [European person] so he was like scared to talk to me and I just go to him and talk to him like “are you ok”? “Oh yeah.” From now on we are friends. I used to give him lunch and he used to give me money and we’re friends now. (Rua, learner, 2018)

Similar points were made by Wha, Tahi, and Rima regarding feeling more confident in their communication with others and feeling they are better able to function in a group situation:

Growing up, we never really used to get out of the house or anything, just stay in the gate pretty much. With my brothers and siblings, so I had five other siblings, so pretty much around my family the whole time. That’s it, never really communicated with other people. Didn’t really talk much to other people. (Wha, learner, 2018)

I used to be a real shy person, didn’t really like communicating with people. But now, after this course, I learnt like I can talk to people and how to talk to them. . . . I learnt how to talk to them, like, “how is your day?” and stuff? (Tahi, learner, 2018)

I would keep to myself, just work on my own but now I can really get into the group work. I would have never done this at school. (Rima, learner, 2019)

Some learners were also clear leaders, and being part of this program enabled their leadership qualities to come to the fore:

Whitu is a natural leader amongst our learners. He is looked up to by his peers, he often has the last say on any matters that may arise within the group. (Feats facilitator, 2019)

The consensus from the learners was that the environment fostered and enabled them to learn about important core values. For example, learners felt there was a genuine respect for people and an ethic of care:

I could have passed, but I didn’t really like schoolwork. Here the work was more simple [because] they helped us properly. Like at school they don’t really care about you. They just give you worksheets and that’s it. Nothing else. (Wha, learner, 2018)

The concept of forgiveness featured heavily in the conversations:

How you treat people. Love your enemies, as you love yourself. No matter what they do to you. (Rua, learner, 2018)

Look after your family no matter what . . . you can have an argument . . . just forgive them. They can make you so angry that you want to beat them up. Just forgive them. . . . My Dad moved away from us when I was 6 years old. . . . That is what made me an angry person . . . my little brother is a young angry man. I just want to teach him that there is more to life than being angry. . . . I want to get that out of him. (Toru, learner, 2018)

I reckon he taught us lots because he always used to tell us stories [about forgiving]. That’s pretty much what helped us out. Life stories, like back home in Samoa (Wha, learner, 2018)

Many learners struggled with mainstream school due to conflicts with others, whether it was with educators or students, and so in any instance where care can be shown and where psychological capital can be developed, learners felt this was very important. Learning to manage emotions, including feelings of anger, and becoming more resilient was especially important. Toru explained,

I was the angriest person, the angriest person. I couldn’t take a joke. When I first started . . . I couldn’t handle the

banter . . . didn’t have a sense of humour. . . . I just took it too seriously . . . it was a little bit better at the start. But I don’t know, by the end of it was we’re all just the same I guess. Everyone was acting the same, talking the same. Made me teach my little brother because he is angry too. Taught him not to take what people say the wrong way, just take it as a joke. (2018)

This point is reiterated by the facilitators:

Toru has grown a lot as person since joining. He is a lot more pleasant to deal with, he’s focused and is in a great head space. He had anger issues when he arrived but he has managed to find ways to deal with issues in a positive way. (Feats facilitator, 2018)

As mentioned above, demonstrating care helped learners develop psychological capital, and it was important for the facilitator to model positive core values such as humility and respect to develop trust:

If you come from a space of respect and respecting them [the learners] and seeing them for the potential of what they could be, then you get what you expect. They give it back to you, if you respect them . . . we don’t have a hierarchy here. I’m just Cheree, I’m not the CEO . . . they know if you [care], it is from the heart. (Feats CEO, 2018)

Waru is a bright student. He doesn’t receive a lot of praise in his life and he can doubt himself. He also struggles with authority at times but he can easily be brought back on task with words of encouragement. (Feats facilitator, 2019)

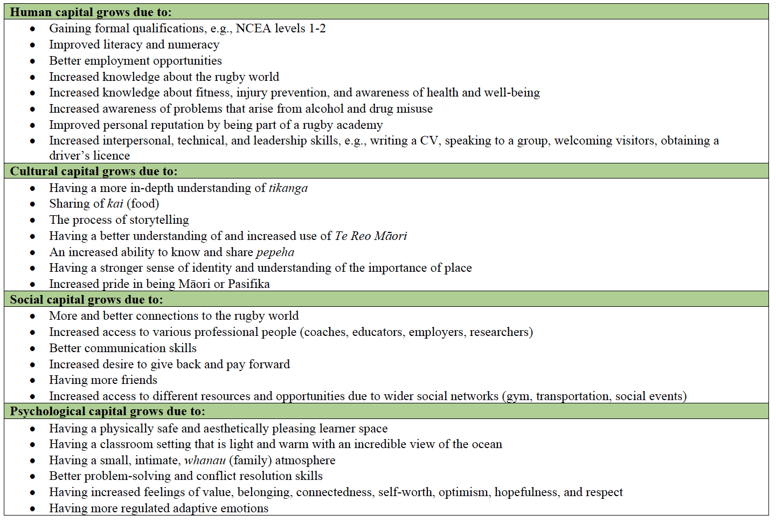

As seen in Table 2, participation in the program results in human, psychological, social, and cultural capital growth.

Table 2 – Capitals grown through participation in the Feats/MPRA program

Capital Contributions to Choices Now and in the Future

Regarding the learners’ goal setting plans, all were able to articulate a career plan for the near or longer term future. Capital links were evident, and some overlap of types of capital are clear. Psychological capital is also evident in many of the statements listed in Table 3.

Table 3 – Examples of capitals contributions shared in Feats learners’ goal-setting plans

DISCUSSION

While sport’s potential impact on poverty reduction is limited, it is the opportunity to add to people’s employability that appears to generate interest in plus-sport initiatives by various stakeholders (Dudfield, 2019). Dudfield (2019) notes, “Supporting vocational skill development, employability and the improved entrepreneurial capability of young people are typical policy interventions in response to youth underemployment and unemployment” (p.122). It is not uncommon to find sport-based initiatives and programs that focus on job-skills training, leadership, and empowerment in an attempt to add to participants’ employability.

One of the biggest challenges facing sport-for-employability organizations (similar to organizations in the broader field of SFD) is that claims that are made often lack evidence (Coalter, 2013; Jeanes & Lindsey, 2014), and there is a dearth of skills and knowledge with regards to monitoring and evaluation (Coalter & Taylor, 2010; Kay, 2009). These are also challenges that organizations like MRPA/Feats face. Problematically, indicators of success can also be narrow, where metrics focus on enrollment and completion rates as opposed to listening to the stories of participants. Moreover, because there is little evidence of Indigenous input into the broader field of SFD theorization, policy, and practice (Lyras & Welty Peachy, 2011), the same applies for sport-driven change interventions, such as employability programs, despite the fact that Indigenous populations are often the focus (Hapeta et al., 2019).

If we are to address some of these challenges, we need to consider alternative ways of exploring what is happening in SFD initiatives in which the focus is on increasing access to education, vocational skill development, and improving employability and entrepreneurial capability for the purpose of enabling participants to better compete in labor markets. While not the only approach, livelihoods and capital analysis is one such suggestion. Livelihoods scholars argue the importance of participatory, bottom-up approaches as an important step in understanding more deeply the complexities of peoples’ lives and experiences (Chambers & Conway, 1992). In particular, livelihoods scholars advocate for listening to and responding to the voices, ideas, and realities of participants and understanding and working with local communities. For example, TRFU’s MPRA manager, Jack Kirifi, believes his role is to “open doors and provide opportunities . . . to other life skills that they [learners] need to know and opportunities in the big world of rugby. All our learners, past and present, have a significant role to play in our community and I want to help them see that . . . to help Pasifika Island players and their communities to be aware of the opportunities in rugby and ensuring they are supported” (2019).

Livelihoods scholars argue that people are more likely to have sustained livelihoods when they have a variety of capital types to draw on (Chambers, 1995), noting there are different sorts of capital (Bourdieu, 1986; Moser et al., 2001; Murray & Ferguson, 2002) and that context determines which capital types are most relevant (Chambers & Conway, 1992; Levine, 2014). While there is no doubt that their MPRA experiences helped learners develop human and social capital, many of them already possessed varying levels of these, whether this was human capital (as NCEA Level 1) or social capital (having supportive relatives or a solid friend group). What the program seemed to do was expand human capital as learners participated in the gym and learned about health and well-being, for example, or they learned a new skill such as driving, which is a “hard skill” important for employability. By also considering psychological capital, some of the soft skills of the learners become more apparent, and as stated previously, it is these attitudes and attributes that employers state they value (Coalter et al., 2016). The MPRA/Feats case example highlights that sport as a vehicle for livelihoods via education initiatives needs to think beyond the end goal of training and education and qualifications (hard skills), thus increasing human capital. Soft skills might be the most important, albeit the hardest to evidence. In this case, increasing cultural capital and psychological capital were key to unlocking potential and making more out of human and social capital.

While it is important to understand learners’ capabilities and things that might hinder their capabilities, as outlined by Coalter et al. (2016), the many “potential environmental obstacles such as unsupportive family situations or lack of employment opportunities” will not be addressed by sport alone (p.12). Sport-for-employability organizations need to work with a range of relevant local organizations to address such wider issues (Coalter et al., 2016). What Coalter et al. (2016) argue is the need for a more holistic approach in using sport to increase employability. They also highlight partnerships as vital, such as that seen between TRFU, MPRA, and Feats.

In starting from a strength-based perspective, Feats looks to focus on what learners already have, not just what learners need. In doing so, Feats recognizes a learner’s inherent potential. Thus, with an actor-oriented approach, the MPRA and Feats positioned learners as active agents who can make choices and devise strategies. Feats also recognizes how learners’ possibilities and choices are shaped by broader structures of society in which they live, positive or negatively. Organizations likes Feats and initiatives such as the MPRA are extremely important because for many youth excluded from mainstream education, opportunities like this might be their only hope to grow their capital, which is important to a sustainable livelihood. However, we also need to be realistic that there are limits to what MPRA and Feats can achieve. What is required is an education system and a society in which all students can thrive and do not languish and a world where organizations like Feats are not required. In the meantime, however, they offer huge hope.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Since the 1980s, many development agencies and practitioners have been preoccupied with livelihoods analysis as a means of understanding and addressing growing social and economic inequity. For the first time, in the context of “no one left behind,” high income countries in the global North have agreed to look inwards at their own injustices and issues of inequality, poverty, and marginalization. In Aotearoa, Māori and Pasifika people more likely face poverty that other groups due to experiencing higher unemployment or possessing jobs that are low skilled, short-term or casual, and poorly paid. While education has long been pushed as means by which people increase their chances of employment and career prospective, the same institutional and societal structures that hinder Māori and Pasifika people in the job market also negatively impact them within the Aotearoa education system. Nearly a decade ago, Māori scholars critiqued the “tail end” of educational achievement, particularly the disparity between outcomes for Indigenous (Māori) and non-Indigenous students. Indeed, the New Zealand Ministry of Education’s then aspirational Māori Education Strategy (MES) was questioned by Erueti and Hapeta (2011) in terms of realizing their lofty goal of closing the gap. Erueti and Hapeta (2011) argued that in order to see desired results, a student’s “cultural capital is clearly significant in terms of the curriculum (content and context) and the values (culture) of the classroom and school” (p.140).

Organizations such as Feats remain important because they provide an alternative opportunity and pathway for education by making the most of the enduring and positive relationship Māori and Pasifika people have with sport, particularly rugby, and using this as a incentive to bring young people back into education. While many learners exit the program with formal qualifications, making them better able to compete in the job market, move on to higher education, or further their training, just as important were the soft skills they acquired. Undertaking a capital and livelihoods analysis of the TRFU and Feats partnership has allowed us to see more clearly different aspects of the MPRA program and bring to the fore other features of the learners’ journeys. While the building of human capital through education is important, of greater significance is the cultural and psychological capital that is built via attendance in this program.

NOTES

1. New Zealand (NZ) will be referred to as Aotearoa unless quoting or making reference to a government document.

2. The NCEA is the main national qualification for secondary school students in Aotearoa and is recognized by employers and used for selection by universities and polytechnics, both in Aotearoa and overseas.

3. Once they enter the Feats program, participants are called learners, which is why this paper uses this term.

4. As of 2017, The World Bank commenced the Human Capital Project, the objective of which is “rapid progress towards a world in which all children arrive in school well-nourished and ready to learn, can expect to attain real learning in the classroom, and are able to enter the job market as healthy, skilled, and productive adults” (World Bank, 2017).

5. The SDGs have been extensively critiqued (Sexsmith & McMichael, 2015), in terms of Indigenous people (Yap & Watene, 2019) and by SFD scholars (Black, 2017; Dudfield & Dingwall-Smith, 2015), however inclusion of these debates is beyond the scope of this paper.

6. SDG 4: To ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (UN, 2016).

7. Te Reo Māori for the numbers 1-4. Aotearoa has 3 official languages, Te Reo Māori, (the Indigenous language), English, and New Zealand Sign Language.

8. The two stages of fieldwork were also to accommodate the busy schedules of MPRA and Feats staff.

9. The two facilitators interviewed in 2019 had also been interviewed in 2018, but the learners interviewed in 2019 were different from those in 2018.

10. Te Reo Māori for the numbers 5-9.

11. Some of the findings in this paper have been previously reported with a different analytical framework in an article for the Journal of Sport Management. See Hapeta et al. (2019).

REFERENCES

Barrett, A. M. (2015). A millennium learning goal for education post-2015: A question of outcomes or processes. Comparative Education, 47(1), 119-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.541682

Black, D. (2017). The challenges of articulating “top down” and “bottom up” development through sport. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 2(1), 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2017.1314771

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital (R. Nice, Trans.). In J. C. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). Greenwood Publishing Group.

Boyd, S., & Hipkins, R. (2015). Getting home runs on the board: Stories of successful practice from two years of the sport in education initiative. Sport New Zealand. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/system/files/SiE-Getting-Runs-on-the-Board.pdf

Brown, S. (2015). Moving elite athletes forward: Examining the status of secondary school elite athlete programmes and available post-school options. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(4), 442-458. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.882890

Brown, S. (2016). Learning to be a “goody-goody”: Ethics and performativity in high school elite athlete programmes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(8), 957-974. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215571145

Brown, S. (2017). “Tidy, toned and fit”: Locating healthism within elite athlete programmes. Sport, Education and Society, 22(7), 785-798. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1085851

Burroughs, D. (2016, August 18). Students gaining NCEA while playing rugby the aim of New Plymouth academy. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/taranaki-daily-news/news/83297283/students-gaining-ncea-while-playing-rugby-the-aim-of-new-plymouth-academy

Chambers, R. (1995). Poverty and livelihoods: Whose reality counts? Environment and Urbanization, 7(1), 173–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789500700106

Chambers, R., & Conway, G. R. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Discussion Paper No. 296. Institute of Development Studies. https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/sustainable-rural-livelihoods-practical-concepts-for-the-21st-century/

Coalter, F. (2013). Sport for development: What game are we playing? Routledge.

Coalter, F., & Taylor, J. (2010). Sport-for-development impact study: A research initiative funded by Comic Relief and UK Sport and managed by International Development through Sport. Comic Relief. UK Sport. Department of Sports Studies, University of Stirling.

Coalter, F., Wilson, J., Griffiths, K., & Nichols, G. (2016). Sport and employability: A report of the Sport Industry Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University for Comic Relief UK. Sport Industry Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University Comic Relief and UK Sport. https://senscot.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Comic-Relief-Sport-and-Employability.pdf

Dalziel, P. & Saunders, C. with Fyfe, R. & Newton, B. (2009). Sustainable development and cultural capital. Official Statistics Research Series, 5. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0f16/8f3039fe204b740334716b852f6af6305c13.pdf

Dudfield, O. (2019). SDP and the sustainable development goals. In H. Collison, S. Darnell, R. Giulianotti & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sport for development and peace (pp. 116-127). Routledge.

Dudfield, O., & Dingwall-Smith, M. (2015). Sport for development and peace and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: Commonwealth analysis report. Commonwealth Secretariat. https://thecommonwealth.org/sites/default/files/inline/CW_SDP_2030%2BAgenda.pdf

Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora: Māori health development. Oxford University Press.

Durie, M. (1999, October). Te pae māhutonga: A model for Māori health promotion. https://www.cph.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/TePaeMahutonga.pdf

Erueti, B., & Hapeta, J. (2011). Ko hauora raua ko te ao kori: He whanau kotahi holistic well-being and the world of Maori movement: One family. In S. Brown (Ed.), Issues and controversies in physical education: Policy, power and pedagogy (pp.125-136). Pearson.

Gratton, C., & Jones, I. (2004). Research methods for sport studies. Routledge.

Hapeta, J., Stewart-Withers, R., & Palmer, F. (2019). Sport for social change with Aotearoa New Zealand youth: Navigating the theory-practice nexus through Indigenous principles [Special issue]. Journal of Sport Management, 33(5), 481-492. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0246

Harrison, H., Birks, M., Franklin, R., & Mills, J. (2017). Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Article 19. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2655

Hipkins, R., & Joyce, C. (2015). Review and maintenance programme (RAMP) science: Themes in the research literature. NZ Ministry of Education.

Horton, P. (2012). Pacific Islanders in global rugby: The changing currents of sports migration. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(17), 2388-2404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.746834

Hudson, M., Milne, M., Reynolds, P., Russell, K., & Smith, B. (2019). Te Ara Tika guidelines for Mäori research ethics: A framework for researchers and ethics committee members. NZ Health Research Council. https://www.hrc.govt.nz/resources/te-ara-tika-guidelines-maori-research-ethics-0

Human Rights Act of 1993 (New Zealand). Public act, No. 82. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1993/0082/latest/DLM304212.html

Human Rights Commission, Te Kāhui Tika Tangata. (2019). Right to education. Health Research Council. https://www.hrc.co.nz/our-work/social-equality/education/

Hunter, J., Hunter, R., Bills, T., Cheung, I., Hannant, B., Kritesh, K. & Lachaiya, R. (2016). Developing equity for Pāsifika learners within a New Zealand context: Attending to culture and values. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 51(2), 197-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-016-0059-7

Huysmans, Z., Clement, D., Whitley, M., Gonzalez, M., & Sheehy, T. (2019). “Putting kids first”: An exploration of the teaching personal and social responsibility model to youth development in Eswatini. Journal of Sport for Development, 7(13), 15–32. https://jsfd.org/2019/07/01/putting-kids-first-an-exploration-of-the-teaching-personal-and-social-responsibility-model-to-youth-development-in-eswatini/

Jeanes, R., & Lindsey, I. (2014). Where’s the “evidence?” Reflecting on monitoring and evaluation within Sport-for-Development. In K. Young & C. Okada (Eds.), Sport, social development and peace (pp.197-217). Emerald Group Publishing.

Jeanes, R., Spaaij, R., Magee, J., & Kay, T. (2019). SDP and social exclusion. In H. Collison, S. Darnell, R. Giulianotti & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sport for development and peace (pp. 152-16). Routledge.

Kay, T. (2009). Developing through sport: Evidencing sport impacts on young people. Sport in Society 12(9), 1177-1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430903137837

Keegan, R. J., Harwood, C. G., Spray, C. M., & Lavallee, D. (2014). A qualitative investigation of the motivational climate in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(1), 97-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.006

Levine, S. (2014). How to study livelihoods: Bringing a sustainable livelihoods framework to life. Working Paper 22. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium. https://securelivelihoods.org/wp-content/uploads/How-to-study-livelihoods-Bringing-a-sustainable-livelihoods-framework-to-life.pdf

Long, N. (2001). Development sociology: Actor perspectives. Routledge.

Luthans, F., Youssef, C.M., & Avolio, B.J. (2007). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford University Press.

Lyras, A., & Welty Peachey, J. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Management Review, 14(4), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.05.006

McLeod, J., Brown, S., & Hapeta, J. (2011). A bicultural model, partnering settlers and indigenous communities: Examining the relationship between the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi and health and physical education. In S. Brown (Ed.), Issues and controversies in physical education: Policy, power, and pedagogy (pp. 3-14). Pearson.

Meo-Sewabu, L., Hughes, E., & Stewart-Withers, R. (2017). Pacific research guidelines and protocols. Pacific Research and Policy Centre & Pasifika@Massey Directorate. https://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/fms/Colleges/College%20of%20Humanities%20and%20Social%20Sciences/pacific-research-and-policy-centre/192190%20PRPC%20Guidelines%202017%20v5.pdf?4D6D782E508E2E272815C5E3E1941390

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

Milne, A. (2010). Colouring in the white spaces: Developing cultural identity in mainstream schools. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Waikato]. Research Commons. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/7868

Milne, A. (2016). Where am I in our schools’ white spaces? Social justice for the learners we marginalise. Middle Grades Review, 1(3), Article 2. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1035&context=mgreview

Moser, C., & Norton, A. with Conway, T., Ferguson, C., & Vizard, P. (2001). To claim our rights: Livelihood security, human rights and sustainable development. ODI. http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/tcor.html

Murray, J., & Ferguson, M. (2002, January). Women in transition out of poverty. In C. Letemendía (Ed.), A guide to effective practice in promoting sustainable livelihoods through enterprise development. Women and Economic Development Consortium. http://www.canadianwomen.org/sites/canadianwomen.org/files/PDF%20-%20ED%20Resource-WIT-guide.pdf

Neill, A., & Hipkins, R. (2015). Review and maintenance programme (RAMP) mathematics and statistics: Themes in the research literature. New Zealand Ministry of Education.

New Zealand Qualifications Authority (2019, July 30). External evaluation and review report: Feats Ltd. pp.1-14. http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/nqfdocs/provider-reports/8692.pdf

Robinson, D., & Williams, T. (2001). Social capital and voluntary activity: Giving and sharing in Māori and non-Māori society. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 17, 52-71. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj17/17-pages52-71.pdf

Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820503

SDGFund. (2018). The contribution of sports to the achievement of the sustainable development goals: A toolkit for action. https://www.sdgfund.org/sites/default/files/report-sdg_fund_sports_and_sdgs_web_0.pdf

Sexsmith, K., & McMichael, P. (2015). Formulating the SDGs: Reproducing or reimagining state-centered development? Globalizations, 12(4), 581– 596. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2015.1038096

Sherry, E. (2017). The impact of sport in society. In T. Bradbury & I. Boyle (Eds.), Understanding sport management: International perspectives (pp. 29-44). Routledge.

Snyder, M. (2007). Gender, the economy and the workplace: Issues for the women’s movement. In L. E. Lucas (Ed.), Unpacking globalization: Markets, gender, and work (pp. 11-20). Lexington Books.

Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2013). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

Statistics New Zealand. (2013). 2013 census. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census.aspx

Statistics New Zealand. (2015). New Zealand in profile 2015: An overview of New Zealand’s people, economy, and environment. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/nz-in-profile-2015.aspx

Stewart-Withers, R. (2020). Sport as a vehicle for livelihoods creation. In E. Sherry & K. Rowe (Eds.), Developing sport for women and girls (pp. 147-160). Routledge.

Stewart-Withers, R. R., & O’Brien, A. P. (2006). Suicide prevention and social capital: A Samoan perspective. Health Sociology Review, 15(2), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2006.15.2.209

Stewart-Withers, R., Sewabu, K., & Richardson, S. (2017). Rugby union driven migration as a means for sustainable livelihoods creation: A case study of iTaukei, Indigenous Fijian. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(9), 1-20. https://jsfd.org/2017/08/01/rugby-union-driven-migration-as-a-means-for-sustainable-livelihoods-creation-a-case-study-of-itaukei-indigenous-fijians/

Taranaki Rugby Football Union. (2019). Benefits for Ngaia-Ratima in Māori and Pasifika academy. https://www.trfu.co.nz/newsarticle/74376

United Nations. (2016). Sustainable Development Goals. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/

UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2011). Sustainable livelihoods: A broader vision. Social support and integration to prevent illicit drug use, HIV/AIDS and crime. Discussion paper. https://www.unodc.org/documents/drug-prevention-and-treatment/UNODC_Sustainable_livelyhoods.pdf

World Bank. (2017). About the human capital project. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital/brief/about-hcp

Yap, M., & Watene, K. (2019). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Indigenous peoples: Another missed opportunity? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 20(4), 451-467. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2019.1574725