Marika Warner1, Jackie Robinson1, Bryan Heal1, Jennifer Lloyd2, Patrick O’Connell1, Letecia Rose1

1 MLSE Launchpad, Canada

2 Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada

Citation:

Warner, M., Robinson, J., Heal, B., Lloyd, J., O’Connell, P. & Rose, L. (in press). “A comprehensive sport for development strategy using collaborative partnerships to facilitate employment among youth facing barriers.” Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

The collaborative development and delivery of “plus sport” employment training programs are promising strategies to increase work readiness, life skills, and employment among youth facing barriers to positive development in a North American urban context. Three programs developed and delivered at MLSE LaunchPad, a large urban sport for development facility in Toronto, Canada, provide a precedent for further implementation and study of collaborative programs that incorporate intentionally designed sport activities into a youth employment program. Strategic codevelopment and codelivery of “plus sport” programs with collaborative community partners and a mixed funding model involving professional sport organizations, charitable foundations, corporate partners, individual donors, and various levels of government are recommended to maximize sustainability and impact. Learnings to date at MLSE LaunchPad point to several key programming components for the successful delivery of youth sport for development employment training in a context of high youth unemployment rates disproportionately impacting youth facing barriers and a rapidly evolving job market.

From the Field Article

The Youth Employment Landscape

Canada’s youth unemployment rate is 10.3%—nearly double that of the general population (Statistics Canada, 2019). The national average, however, does not reflect the higher youth unemployment rates seen in specific regions of the country. In Ontario, youth unemployment is above the national average at 12.7% and up to double the overall provincial unemployment rate due to growth in the youth labor force that exceeds growth in available jobs (Geobey, 2013; Government of Ontario, 2018; St. Stephen’s Community House & Access Alliance [SSCHAA], 2016). During times of economic recession, Ontario’s youngest workers have experienced the most adverse employment outcomes (Geobey, 2013; SSCHAA, 2016). In the city of Toronto, youth unemployment is 13.4%—the highest of any region in Ontario—and has trended above the national average since the early 2000s (Geobey, 2013; Government of Ontario, 2018). This trend relates to an increased representation of youth facing barriers, including racialized (nonwhite) and newcomer youth (youth new to Canada). The high unemployment rate also relates to the policy, infrastructure, and economic composition of Toronto (Bolíbar et al., 2019; City of Toronto, 2018; Geobey, 2013) and demonstrates a consistent failure in policies designed to address youth employment issues (Bancroft, 2017; SSCHAA, 2016). Growing structural inequities profoundly impact business and educational institutions and create barriers to employment for racialized and low-income youth (Geobey, 2013). Systemic racism and asymmetry in educational and economic resources constrain occupational attainment among these populations, particularly in neighborhoods that face significant social and economic challenges, including high rates of poverty, homelessness, and criminal activity (Diemer, 2009; Sabeel Rahman, 2018). Racial disparity in youth employment outcomes is apparent in Toronto, with unemployment rates up to 23.9% among racialized youth and 28.0% among Black youth (SSCHAA, 2016).

Further, youth unemployment acts as a trigger for increased poverty and social isolation, cumulative disadvantages that make it even more challenging to obtain a job (Bolíbar et al., 2019). Chronic unemployment harms the support networks of young people from low-income backgrounds, reducing the presence of resourceful contacts among these youth (Bolíbar et al., 2019). Precarious employment also leads to adverse health outcomes, exclusion from resources, and decreased access to social services, including employment training (Briggs, 2018; Mayhew & Quinlan, 2002). Yet accountability for youth unemployment continues to fall on individual youth, who are pressured to take full responsibility for their employment status even while contending with vast and intersecting structural inequities (Bancroft, 2017; Sabeel Rahman, 2018). Among youth who are employed, working poverty and precarious employment are common issues (Briggs, 2018; Statistics Canada, n.d.; The Blagrave Trust, 2018), and full-time earnings continue to fall (Kershaw, 2017). Workplace discrimination is a well-documented reality (PricewaterhouseCoopers [PwC], 2018; SSCHAA, 2016), and youth who face barriers to positive development, including racialized and newcomer youth, are more likely to struggle to secure work and remain employed (Briggs, 2018; Liang et al., 2017; Santos-Brien, 2018; The Blagrave Trust, 2018). Individuals who faced barriers including trauma, poverty, or other social marginalization as adolescents are less likely to be employed and much less likely to have a high-quality job at age 29 (Ross et al., 2018).

Youth employment plays a significant role in generating social stability and positive health outcomes for individuals, families, and communities (Briggs, 2018; Liang et al., 2017; Mumcu et al., 2019; SSCHAA, 2016). Having a job between ages 13 and 17 predicts higher job quality in adulthood with significant implications relating to income and well-being (Ross et al., 2018). However, youth face a range of difficulties in finding and keeping work. Transitions encountered during late adolescence and emergent adulthood present issues that may negatively impact employment outcomes (Lane & Carter, 2006; Liang et al., 2017; The Blagrave Trust, 2018).

Beyond job precarity, discrimination, and inequity in networks and social capital, significant obstacles to sustainable employment relate to levels of education, skills, and experience as well as mental health, attitudes, and motivation (Liang et al., 2017; Sack & Allen, 2019; SSCHAA, 2016). Youth, particularly those who are out of school and without postsecondary credentials, need improved on-ramps to workforce engagement (Ross et al., 2018; Sack & Allen, 2019). Work readiness and life skills also play significant roles in a successful job search and ongoing job retention, with employers frequently citing a lack of “soft skills” or life skills as a central reason for the termination of new employees (Ross et al., 2018).

Challenges in Youth Employment Training

Rigorous evaluations of youth employment programs demonstrate mixed and modest results overall (Bloom & Miller, 2018; Matsuba et al., 2008; SSCHAA, 2016), pointing to a scarcity of engaging and impactful job training programs for youth. Some programs succeed in providing practical job training skills but do not demonstrate impact relating to other relevant domains such as self-concept and life skills (Matsuba et al., 2008). Employer expectations for work readiness and life skills have grown since 2000 (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019) placing an increased yet unmet demand on providers of youth employment training to develop novel and innovative tactics to deliver on these outcomes (Matsuba et al., 2008; Bloom & Miller, 2018). Other programs have not evolved sufficiently to keep pace with rapid changes in the job market, creating a mismatch between skills and demand and resulting in an overrepresentation of youth in low-wage jobs without specialized skill requirements (The Blagrave Trust, 2018). Existing job training programs may tend to mobilize youth for low-quality low-wage work (Spaaij et al., 2013) instead of jobs that offer stability, self-esteem, and a living wage (Briggs, 2018).

Advancements in technology have created a demand for new skills and capabilities in the labor force while rendering others obsolete (PwC, 2018). There is an increasing risk of loss of talent to support Canada’s skilled labor force, particularly in the digital and information technology sectors (PwC, 2018). The youth employment training sector’s response to these shifts has been insufficient, and vocational pathways are continually undervalued in the creation and delivery of youth employment training supports (The Blagrave Trust, 2018). Local needs assessments in downtown neighborhoods such as Toronto’s Moss Park have uncovered strong interest in and demand for accessible vocational training for youth (SSCHAA, 2016). Yet, few such programs exist in these geographical areas.

Establishing adequate youth employment training resources is likely to be time consuming and resource intensive (PwC, 2018). These factors result in the reproduction of existing programs that have not demonstrated an ability to support youth to reach their employment-related objectives. Community-based organizations and collaborative partnership approaches are typically underutilized in the provision of employment support for youth (Sack & Allen, 2019), with the bulk of services delivered in isolation by municipal and higher levels of government. This model may present additional obstacles to youth already facing barriers to employment, and employment training resources located in neighborhoods and provided by trusted community organizations are likely to increase access to such services.

The factors discussed above that contribute to adverse youth employment outcomes involve significant structural and systemic causes that cannot be addressed simply through employment training programs and a positive youth development (PYD) approach (PwC, 2018; Sabeel Rahman, 2018; Santos-Brien, 2018; The Blagrave Trust, 2018). Beyond individual skill development, elements of social inclusion such as housing, urban planning, transit, and child care must also be considered in programming and policy making to authentically address youth employment as a complex social issue (Coalter, 2015; SSCHAA, 2016).

Program Setting and Population

Youth facing barriers to positive development are the intended beneficiaries of the sport for development (SFD) strategy described below. Youth facing barriers are defined as youth who may require additional supports and services to reach their full potential. In the context of MLSE LaunchPad, a SFD facility located in downtown Toronto, those facing barriers include racialized youth, Indigenous youth, low-income youth, youth with disabilities, homeless or underhoused youth, youth in foster care or leaving care, 2SLGBTQ youth, newcomer youth, and youth in conflict with the law.

MLSE LaunchPad occupies the ground floor of a subsidized housing building. The local area has a high proportion of subsidized housing and the highest density of homeless shelters in Canada (Dhungana, 2012; James, 2010; Kumbi, 2013), exhibits high rates of poverty, and is home to many low-income families, including over 3000 low-income youth (City of Toronto, 2011, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c). Approximately 50% of the neighborhood’s population was born outside of Canada. Over 60% of residents are racialized individuals, and Black and South Asian are the predominant racialized groups (City of Toronto, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c). Disproportionate numbers of youth from low-income families and racialized neighborhoods such as Moss Park have few work opportunities beyond low-wage, precarious employment (Briggs, 2018). The area also has serious safety issues with a high rate of criminal activity (CBC News, 2012). Demographic data collected from youth participants at MLSE LaunchPad indicate that 88.67% identify as racialized youth with the highest representation among Black youth at 33.83%. Of the youth polled, 76.76% report an annual household income less than $30,000 (MLSE LaunchPad, 2018/19) below the low-income cutoff for a family of three in the province of Ontario. Within the local community, youth unemployment is a prevalent concern (City of Toronto, 2018), and many youth face barriers to finding and keeping paid jobs.

Objective

This study responds to the “need for theoretically informed explanations of the ways that sports and sport participation can be organized and combined with other activities for the purpose of empowering young people” (Coakley, 2011, p. 318). We report on our experience with collaborative development and delivery of “plus sport” employment training programs in a community-based SFD setting and the application of evidence-based strategies and tactics in programming. Specific research questions are as follows:

- Is the implementation of “plus sport” youth employment training programs feasible in an urban SFD setting?

- Does a collaborative partnership and funding model support the sustainable delivery of such programs?

- What is the impact of such programs on youth employment and related outcomes?

By applying a systematic framework for observation and measurement of program outcomes, this experiment questions the neoliberal approach to sport for youth development, wherein sport inevitably leads to individual and community development, which has typically been supported by anecdotal evidence (Coakley, 2011, 2015). In the programs discussed, employment training acts as the hook to attract youth whose goals include finding and keeping paid work. Employment and related outcomes are the primary focus, and sport is an additional context for teaching skills and behaviors that contribute to employment outcomes. This approach is a promising strategy to increase work readiness, life skills, and employment levels among youth facing barriers in a Western urban context (Spaaij et al., 2013; Walker, 2018; Walker et al., 2017).

Beyond a programmatic focus on individual development, the approach aims to impact government policy and sector-wide standards for the provision of employment training services by testing and refining an approach to youth employment training that is community based, youth focused, and evidence based. The findings discussed may be applied and further researched in SFD and youth development contexts, from front-line program delivery to policy setting. However, critical discourse relating to this novel approach is required to tease out the further potential for impact, applicability in various settings and with multiple populations, and theoretical and practical implications. To stimulate dialogue on key learnings to date and to catalyze cross-sectoral discussion of the utility and application of this strategy, this paper describes and explains MLSE LaunchPad’s collaborative partnership approach to implementing a comprehensive SFD strategy to increase positive youth outcomes relating to employment.

Current Best Practices in Youth Employment Training

The Youth Employment Index identifies five key factors essential to accelerating a young person’s path to employment through a collaborative partnership approach: (a) people and leadership skills, (b) access to networks, (c) formal qualifications, (d) relevant experience, and (e) practical job application skills (PwC, 2018). These factors establish a framework for youth employment training that is supported by a range of literature in the SFD and PYD fields (Fraser-Thomas et al., 2005; Lyras & Welty Peachy, 2011; Matsuba et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2018; Sack & Allen, 2019; Santos-Brien, 2018; Spaaij et al., 2013).

Training programs designed to improve youth employment outcomes should include holistic wraparound services such as counseling, mentoring, and guidance components (Arellano et al., 2018; Cragg et al., 2018; Matsuba et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2018; Santos-Brien, 2018; SSCHAA, 2016; Whitley et al., 2018), income support (Santos-Brien, 2018), and nonemployment focused activities (Santos-Brien, 2018) to address internal and external barriers to employment (Sack & Allen, 2019; Spaaij et al., 2013). A PYD approach to employment training is recommended, with a focus on personal strengths and the growth of positive developmental assets through appropriately structured activities delivered in a safe environment (Ross et al., 2018). Ideal employment supports are “one-stop shops” located in and responsive to local communities (Santos-Brien, 2018) and supported by multistakeholder partnerships to incorporate a diversity of expertise relating to employable skills training, work readiness including job search skills, life skills development, and mental health (Spaaij et al., 2013). The involvement of multiple partners in design and delivery may help ensure that programs align with regional needs—another recognized factor influencing program outcomes (Ross et al., 2018). While prioritizing a welcoming and relaxed informal atmosphere (Ross et al., 2018; SSCHAA, 2016), programs should engage employers both in program design and delivery and as postprogram entry points into the labor market (Santos-Brien, 2018).

Successful programs address the specific and tangible obstacles that youth face in entering and remaining in the workforce, including underlying psycho-socio-emotional issues (Matsuba et al., 2008). Program components designed to increase confidence and motivation play an important role in addressing such obstacles (Santos-Brien, 2018). A comprehensive approach should develop positive psychological traits in addition to skills training and work experience (Matsuba et al., 2008). Participation in career or technical education that is relationship based is related to higher job quality and is a practical approach to addressing barriers to quality employment for youth. Relationship-based training takes place at the workplace in whole or in part and explicitly or implicitly involves a relationship with an adult or supervisor (Ross et al., 2018). This approach benefits from the integration of multiple community partners. Work-based learning (Ross et al., 2018), apprenticeships (Sack & Allen, 2019), and volunteer experiences (Spaaij et al., 2013) offer potential contexts to deliver relationship-based employment training. Community-based organizations are well positioned to connect youth who are not currently working or in school to these programs (Sack & Allen, 2019). One collaboratively delivered Boston-based program demonstrated positive impact resulting from an integrated curriculum combining work experience and job readiness curricula (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019).

The use of formal eligibility criteria for youth employment training programs increases the likelihood that youth who enter programs will complete the program and experience the intended benefits (Bloom & Miller, 2018). Programs appear to be more effective for young people who possess sufficient intrinsic motivation and some established base competencies (Spaaij et al., 2013). Training programs should also offer relevant formal qualifications and credentials that align with current local job market demands (Sack & Allen, 2019; Santos-Brien, 2018). Credentials and certifications increase individuals’ ability to secure stable employment, decreasing vulnerability to long-term marginalization (Briggs, 2018). By employing these documented best practices, programs may allow youth to gain work readiness skills appropriate both to the individual youth and the local context (Ross et al., 2018).

Youth summer employment programs are a relatively common intervention in youth employment training. Based on available evidence, this style of programming should not be overlooked as a potentially impactful tactic and has the potential for far-reaching and long-term positive outcomes (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019). Summer work programs appear to be more impactful for “at-risk” youth. Such programs may help to ameliorate adverse employment outcomes—including unemployment, low income, and low-quality work—experienced at increased rates by youth who face barriers to positive development (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019). Mechanisms of impact for summer employment programs include improving behaviors related to academic success, increasing career and educational aspirations, reducing opportunities to engage in negative behavior, and providing direct income support to youth and their families (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019).

SFD and Employment Training: Existing Connections and Gaps

Programs with employment as an intended outcome make up a small proportion of SFD programs worldwide. Recent review articles have created international listings of programs utilizing SFD to address various thematic issues, including livelihoods. Programs that targeted livelihood issues made up 5-17% of all SFD programs included (Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Svensson & Woods, 2017). In another recent review article, of 46 studies of youth SFD interventions, only two included outcomes related to employment (Whitley et al., 2017).

One qualitative study examined the impact of two programs combining education with sport activities to increase youth employability (Spaaij et al., 2013). These programs included multisector involvement from partners in professional sport, government, and charitable organizations. The integration of sport in program content was critical in achieving positive employment outcomes, including increased social and job search skills (Spaaij et al., 2013). Issues with the sustainability of youth employment postprogram (Spaaij et al., 2013) suggest that more significant postprogram support and follow-up may increase long-term outcomes.

The subject of life skills transference stemming from sport experience has been theorized and reported extensively with the conclusion that life skills developed through sport likely do not transfer automatically from one domain to another, for example from sport to the workplace (Whitley et al., 2019). Intentional program design bridging the gap between sport and workplace contexts and integrated curriculum including sport activities designed to foster development, practice, and transfer of life skills are necessary to support the transference of life skills developed in a SFD setting to the workplace (Petitpas et al., 2005; Turnnidge et al., 2014; Whitley et al., 2019). Other conditions known to facilitate life skills transference to nonsport settings include coach support to identify life skills developed through sport activities and how these life skills may be applied in other settings, strategizing and practicing the application of life skills in a variety of contexts, and debriefing experiences of applying life skills. Program design should also include elements in the sport setting that relate to other domains of life and provide real-life examples of life skills application outside of sport including involvement of past participants and other relatable role models (Camiré et al., 2007; Danish et al., 2005; Gould & Carson, 2008; Petitpas et al., 2005; Turnnidge et al., 2014).

Projections predict that the sport industry is likely to create new jobs in the immediate future (Mumcu et al., 2019). Despite concerns regarding public–private partnerships in the provision of social services (Collins & Haudenhuyse, 2015), the community sport and professional sport industries may be valuable partners for creating and delivering responsive and engaging youth employment training programs. Sport-based partnerships have the potential to develop programs that align with current and future job market demands, including emerging opportunities in the sport industry and related industries such as hospitality and technology. Positive youth development is more likely to be achieved when sport programming is strategically combined with nonsport programming to promote specific objectives. Thus, employment training programs developed and delivered in partnership with the professional sport and SFD sectors are promising avenues for long-term youth and community impact (Jones et al., 2017).

Further, SFD organizations may be well positioned to manage such partnerships effectively. A recent study used social network analysis to explore characteristics of cross-sectoral networks that promoted sport and civic participation among individuals facing barriers and concluded that sport organizations should coordinate such systems (Dobbels et al., 2018). Cross-sector partnerships also present several challenges relating to impact and sustainability. Pertinent challenges in the context of this field report include partner skepticism regarding sport as a tool for PYD, the potential for power imbalances, and lack of alignment regarding objectives, which may contribute to mission drift (MacIntosh et al., 2016; Welty Peachy et al., 2018). Simple and clearly stated objectives that align with each partner’s stated purpose is a necessary component for cross-sector partnership in SFD (MacIntosh et al., 2016).

SFD programs designed to address employment outcomes have received little attention in research and evaluation (Darnell et al., 2018; Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Spaaij et al., 2013; Svensson & Woods, 2017; Whitley et al., 2017). The potential to impact livelihoods is one of the least studied areas of SFD (Svensson & Woods, 2017). The focus of study in the SFD field has predominantly been on educational and emotional outcomes and social cohesion (Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Svensson & Woods, 2017) without consideration of employment and income as mediators of these other outcome domains—one limitation in the literature and a possible avenue for future study. Further, transference between sport and external contexts represents a small portion of the research body (Jones et al., 2017), which highlight several limitations to the presumed transferability of life skills learned and adopted in a sport context (Petitpas et al., 2005; Turnnidge et al., 2014; Whitley et al., 2019). Rigorous short- and long-term mixed methods evaluations of SFD programs with employability and employment as primary objectives offer a means to assess the transference between sport and the workplace. Research and program evaluations that follow youth throughout their participation in a “plus sport” employment training program and later in their work environment offer great potential for learning relating to the transference of life skills and other cognitive and emotional outcomes of SFD outside the sport context. Further, the development and application of positive youth outcomes in sport and nonsport contexts are typically studied separately (Jones et al., 2017). The results of programs integrating sport into youth employment training may have substantial implications for future best practice in youth employment training and SFD.

An Evidence-Informed Approach to Youth Employment Training in Sport for Development

The current study draws from the literature outlined above, which provides substantial direction for SFD programming organizations seeking to impact youth employment outcomes and for youth employment service organizations considering how to increase their impact through creative innovation and collaboration. The programs discussed below include multiple tactics supported by the extant literature, including wraparound services, income support, and activities not directly related to employment (Matsuba et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2018; Santos-Brien, 2018; Spaaij et al., 2013). A relationship-based approach to PYD builds soft skills, job search skills, and social capital (PwC, 2018; Ross et al., 2018). Formal credentials and work experience are realized through a community-based, collaborative, and centralized service delivery model in an inclusive setting (Santos-Brien, 2018; Spaaij et al., 2013). Application of appropriate eligibility criteria and intentional alignment with local job market demands increases the likelihood of a positive impact (Ross et al., 2018; Sack & Allen, 2019; Santos-Brien, 2018). While not directly proposing a SFD approach for youth employment training, the literature reviewed support multiple aspects of the strategy detailed in this field report and suggest further exploration of this approach (Petitpas et al., 2005; Spaaij et al., 2013; Whitley et al., 2019).

MLSE LaunchPad’s Ready for Work Strategy

The intention of MLSE LaunchPad’s Ready for Work programming pillar is to offer a comprehensive strategy to address youth employment outcomes through SFD. The approach includes a range of “plus sport” employment training programs developed and delivered in close collaboration with local partner organizations with similar intended outcomes and strong reputations in the community. MLSE LaunchPad’s approach to employment training views sport and physical activity as potentially powerful tools to teach the skills required to gain meaningful and sustainable employment and focuses primarily on interrogating the impact of SFD on individual development with a secondary focus on community development. SFD’s role in societal development, while a crucial question, is beyond the scope of this program evaluation. Although structural inequity is recognized as a necessary strategic focus to enable long-term social change (Sabeel Rahman, 2018), deep-rooted systemic inequities are not expected to be modifiable through this approach. This approach focuses on strategies that complement structural change while enabling economic participation in the short and medium term.

The facility offers job skills training programs that combine classroom or kitchen-based learning with on-court sport components in an integrated curriculum to assist youth in gaining both the technical and “soft” skills required for employment in a variety of sport and nonsport settings. Youth are recruited through word of mouth and employment training partners. These recruitment tactics align with the “plus sport” approach, wherein youth primarily access the program for employment training and job search support, and sport is an additional teaching tool to assist youth in achieving their work-related objectives. It stands to reason that the pervasiveness of the “Great Sport Myth”—a strong belief in the inherent purity and goodness of sport (Coakley, 2015)—may aid the use of sport as a hook for youth participants and for program delivery partners wishing to incorporate sport into their employment training offerings. However, this has not been our experience. The majority (92%) of youth participants entered the program to obtain employment and reported not being aware of the sport component before starting the program, but they did see the sport component as having a positive impact on their job readiness postprogram. Program delivery partners have expressed skepticism regarding the role of sport in an employment training program but have changed their perspectives as a result of the evidence produced in program evaluation and their own systematic observations.

Figure 1 – MLSE Launchpad Theory of Change

Community partner organizations with expertise in the delivery of youth employment services are essential to the program framework. The comprehensive partnership selection and development process begins with an expression of interest by an external community partner organization. As part of the initial partnership assessment, the potential partner organization provides information related to funding and insurance as well as program descriptions to ensure the alignment of the organization’s mandate with MLSE LaunchPad. Critical questions at initial assessment include:

- Does MLSE LaunchPad have the capacity to take on a new employment training partner? MLSE LaunchPad provides several in-kind resources to collaborative partner organizations including staff support by trained and experienced coaches and youth mentors; classroom, kitchen, and court space; access to wraparound services such as counseling and nutrition resources; measurement and evaluation support including customized evaluation frameworks, analysis and reporting; and staff support for the codevelopment of evidence-based program curriculum. Figure 1, the MLSE LaunchPad Theory of Change specific to Ready for Work programs, details these resources.

- Does the partnership align with MLSE LaunchPad’s Theory of Change? MLSE LaunchPad’s Theory of Change includes short- and long-term outcomes relating to employment, including increased work readiness and increased employment among youth age 18-29.

- Does the partnership fill a gap in programming at MLSE LaunchPad? MLSE LaunchPad works to offer a range of programs and services to meet the expressed needs of a growing membership base and engage priority demographics described in the section “Program Setting and Population” above.

- Is there the potential to codevelop a program? Collaborative codevelopment of programs is seen as an ideal path as opposed to mere provision of in-kind resources to support the delivery of an existing program with the addition of a “tacked-on” sport component.

If questions 1-4 are answered affirmatively, the partnership is moved to the next stage in the process: internal consultation. Program staff evaluate whether the facility has the resources to support the collaborative program, including space, equipment, staff expertise, and human resources for curriculum development, program delivery, and oversight. Research and evaluation staff assess the feasibility of rigorously measuring the intended outcomes of the program.

Proposals supported by all parties move on to the discovery and development stage. Critical questions at this stage include:

- What would integration of sport look like for this program? The alignment between skills and outcomes to be developed on- and off-court in the proposed program is assessed to determine what type of sport engagement might complement and enrich the nonsport content.

- What are the needs of this partner, and what would capacity building involve? MLSE LaunchPad’s Theory of Change includes a commitment to collaboratively developing capacity among partner organizations in the youth development sector.

- How can MLSE LaunchPad best focus an approach to measurement and evaluation of this program? An Evaluation Framework Builder document and in-depth consultation are employed to determine primary and secondary program outcomes, appropriate metrics, and evaluation techniques, which typically include a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. Program evaluation frameworks assess the efficacy of the program in achieving its intended outcomes, a focus that supports program quality improvement, increased youth outcomes, and funding solicitation by partner organizations.

The funding model for collaborative partnerships involves financial support for program implementation from both MLSE LaunchPad and the community partner organization. MLSE LaunchPad does not provide direct financial support to partner organizations but offers many in-kind supports, including human resources, with a substantial cost implication. MLSE LaunchPad coaches and youth mentors are embedded in all collaborative programs. Partners are responsible for securing funding to pay staff employed by the partner organization and to support organizational operations external to the facility. The MLSE Foundation funds MLSE LaunchPad through support from the parent company, Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment (MLSE), as well as corporate partners, the provincial government, individual donors, and other fundraising efforts including ticketed events. Partner organizations raise funds through a variety of means, including grants from the municipal, provincial, and federal governments and charitable foundations; corporate and individual donations; and fundraising events.

One example of a collaborative partnership in the Ready for Work pillar is the Digital Customer Care Professional program delivered in partnership with NPower Canada. NPower Canada is a charitable workforce development organization that prepares underserved youth for successful careers in the information and communication technology sector (NPower Canada, n.d.). Classroom-based activities in this intensive 10-week technical support professional training program include technical skills training and the opportunity to earn a Microsoft Office Specialist certification; life skills development with sessions delivered by a mental health provider on topics such as stress management; and job readiness preparation such as mock interviews. Local employers are engaged in the partnership as guest speakers, and program participants are connected to new career opportunities with some of Canada’s largest employers. An on-court physical activity component delivered twice per week for 60 minutes at the end of the program day by MLSE LaunchPad coaches reinforces vital concepts learned in the classroom while developing leadership skills and helping youth learn to balance a healthy lifestyle with the demands of a job. Program evaluation results have been positive with significant increases in the immediate intended outcomes—work readiness and leadership—with 85% of graduates securing employment or enrolled in postsecondary education within six months of completing the program. Additionally, increases in employment, household income, and physical activity level persist at a two-year follow up.

A second example is the Cooking for Life Program developed and delivered in partnership with Covenant House Toronto, Canada’s largest agency serving youth who are homeless, trafficked, or at risk (Covenant House Toronto, 2019). Youth who have completed an introductory seven-week employability skills program at Covenant House are offered a paid eight-week placement in MLSE LaunchPad’s commercial-style community kitchen. Youth work with trained and experienced chef–mentors to learn technical and soft skills in demand in the local food and beverage industry. The placement includes preparing snacks and meals to meet facility needs such as after-school snacks for younger youth and their families, lunches for day campers and other daytime program participants, evening meals provided to league-play participants, staff lunch, and catering for meetings and other internal events. Youth may earn recognized credentials, including a food handler’s certificate—an essential qualification that may be inaccessible for low-income youth due to the testing fee. The program will soon include an integrated and customized sport component—delivered twice per week during program hours at regular times when food preparation activity is minimal—to support youth participants intending to work in the hospitality industry. The sport component will include structured on-court activities that support the development of leadership and communication skills while addressing documented health issues faced by hospitality workers, including injury prevention, chronic pain, depression, anxiety, and stress management (Mayhew & Quinlan, 2002; Zhang et al., 2019). This component will expose youth to new sports and activities while creating healthy physical activity habits and utilizing exercise for stress management. Following program completion, interested youth are connected to sustainable employment at MLSE-owned food-service facilities, where hospitality workers are unionized and earn high wages relative to the industry average (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2019; Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment & Teamsters Local Union 847, 2016). Five program graduates (38% of total program participants) have obtained ongoing employment at MLSE LaunchPad.

The nine-week Leaders In Training (LIT) program offered each summer at MLSE LaunchPad is a third key example. Partners from the education, marketing, sport, recreation, and social service sectors are involved in program implementation. The extensive training provided in the first two weeks includes the acquisition of multiple certifications such as CPR, First Aid, and nationally recognized coaching credentials. The training period also includes professional development related to job search skills, including resume writing and interviewing and personal development workshops such as self-care. The next six weeks involve working with permanent full- and part-time MLSE LaunchPad staff to deliver day camp programs to youth from the local community. The final week of the program offers career exposure activities, including meeting staff from professional and community sport organizations and tours of local sport and sport media facilities. These activities intend to expose youth to a variety of career options in the sport industry, connect youth to potential role models, and increase educational and career aspirations. Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of this program has produced positive results with significant increases in work readiness and leadership. Youth report having developed the confidence and skills to secure jobs after the end of the program. Twelve LITs in three years (24% of total program participants) have become permanent coaching staff at MLSE LaunchPad, and many have described the LIT program as a turning point in their lives.

Before enrollment in any of the programs described, above youth complete a thorough application process customized to each program to help ensure that the youth enrolled are well positioned to participate fully and achieve their objectives. The process involves staff from MLSE LaunchPad and community partner organizations and members of MLSE LaunchPad’s board of directors. It may include an application form with open-ended questions, group and individual interviews, and in some cases, demonstration of credentials such as a high school or general equivalency diploma.

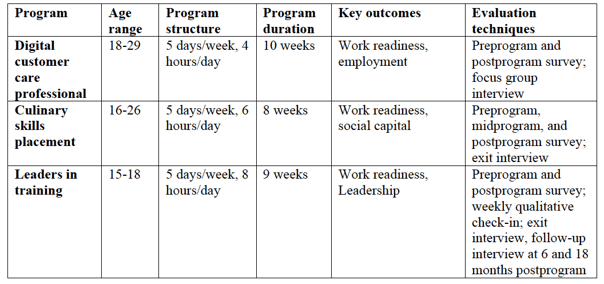

As MLSE LaunchPad members, youth enrolled in collaborative Ready for Work programs have access to a variety of complementary programs and wraparound services. These include drop-in and registered “sport plus” programs, leagues, tournaments, counseling services with mental health providers, nutrition supports, and access to youth mentors. Youth mentors are available during program hours to respond supportively to youth needs, help youth to access facility and community resources, and provide positive and consistent adult relationships. Table 1 displays key information relating to each of the programs described above.

Table 1 – “Ready for Work” program description

Insights from the Field

The above program descriptions provide examples of how the integration of sport in youth employment training programs through a collaborative “plus sport” program delivery model may increase outcomes related to youth employment. Sport can act as a hook that attracts new and different youth to employment training programs. Moreover, sport can be a highly engaging tool to transfer employable skills. The delivery of an employment training program at a community SFD facility creates a welcoming, engaging, and relatable setting for local youth who may not feel comfortable in a traditional learning environment. Within the context of the program, sport has the potential to build relationships, develop social capital, and increase life skills, all of which may, in turn, influence employment outcomes (Spaaij et al., 2013). Psychological well being correlates positively with youth employment, and physical and mental wellness developed through consistent and sustained engagement in sport is likely to contribute to employability (Matsuba et al., 2008).

SFD employment training programs constructed and implemented in alignment with MLSE LaunchPad’s Ready for Work programming model may create positive impacts beyond the typical outcomes of traditional youth employment training programs. Such programs have the potential to support youth to reach their employment-related goals. Key program components include collaboratively developed evidence-based curricula featuring complementary skills training and sport activities; an appropriate screening/admissions process; a physically and psychologically safe environment with the presence of positive relationships; income support for youth wraparound services including mental health counseling; the opportunity to earn recognized and valuable credentials; and a thorough and iterative mixed methods measurement and evaluation framework. With these components in place, employment training “plus sport” is likely to enhance long-term positive youth outcomes directly relating to both employment and participation in sport and physical activity. Funding demands require the alignment of program outcomes with the dominant North American narrative of personal development, which emphasizes individualism and overcoming barriers to improve one’s life (Coakley, 2011). In the case of MLSE LaunchPad, these types of outcomes are successfully supported by a mixed funding model that includes substantial in-kind support provided to community partner organizations made possible primarily by corporate and government support orchestrated by an allied charitable foundation. Strategic codevelopment and codelivery of “plus sport” programs with collaborative community partners and a mixed funding model involving professional sport organizations, philanthropic foundations, corporate partners, individual donors, and various levels of government may maximize sustainability and impact. As MLSE and the MLSE Foundation intentionally move to a more strategic approach to corporate social responsibility, an inherent risk is the blind adoption of the “Great Sport Myth”—an unquestioned belief in the positive qualities of sport and the automatic transmission of these qualities to those who participate in it (Coakley, 2015). An ongoing commitment to rigorous measurement and evaluation is necessary to interrogate critically the benefit of sport in youth development, including in an employment training context.

Limitations of this paper include an implicit social integrationist discourse and a focus on the potential of SFD programs and organizations to impact the supply side of the youth employment equation by enhancing individual youth’s technical and soft skills leading to employment and increased personal income (Spaaij et al., 2013). A future focus on impacting the demand side of youth employment through examining and exploring strategies to reduce obstacles to employment for youth facing barriers, including a deeper grappling with economic structures and systems, is a necessary avenue for a comprehensive exploration of this issue (Sabeel Rahman, 2018).

In light of the successful implementation of the program framework discussed above, the next steps for the authors include mixed methods and participatory action research within the three programs described in this paper. Longitudinal mixed methods research involving Ready for Work program participants, program evaluation reporting on a larger sample achieved through scaling successful programs, and comparisons to non-SFD youth employment training programs will also help to define and explain program impact more clearly (Matsuba et al., 2008).

Conclusion

We have applied a social research lens to the relationship between sport participation, life skills development, work readiness, and employment, moving beyond personal testimony to track and measure program implementation and outcomes. In the context of an individualized approach to SFD, the collaborative development and delivery of community-based “plus sport” employment training programs is a potentially promising strategy to increase work readiness, life skills, and employment among youth facing barriers in a North American urban setting. This approach should be considered by SFD organizations and youth employment service providers as a starting place for new and sustainable programming partnerships that may effectively deliver both SFD and youth employment outcomes. Three example programs developed, delivered, and evaluated at MLSE LaunchPad utilizing a collaborative partnership model provide a precedent for further implementation and study of training programs within this prototype.

REFERENCES

Arellano, A., Halsall, T., Forneris, T., & Gaudet, C. (2018). Results of a utilization-focused evaluation of a Right to Play program for Indigenous youth. 156-164.

Bancroft, L. (2017). Not so NEET: A critical policy analysis of Ontario’s Youth Job Connection Program. Social Justice and Community Engagement, 27.

Blagrave Trust. (2018). Literature review: Young people’s transition to a stable adulthood. https://www.blagravetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Lit-Review-March-2018.pdf

Bloom, D., & Miller, C. (2018). Helping young people move up: Findings from three new studies of youth employment programs (Issue brief). MDRC. https://www.mdrc.org/publication/helping-young-people-move

Bolíbar, M., Verd, J. M., & Barranco, O. (2019). The downward spiral of youth unemployment: An approach considering social networks and family background. Work, Employment and Society, 33(3), 401-421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018822918

Briggs, A. Q. (2018). Second generation Caribbean black male youths discuss obstacles to educational and employment opportunities: A critical race counter-narrative analysis. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(4), 533-549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1394997

Camiré, M., Trudel, P., & Forneris, T. (2007). High school athletes’ perspectives on sport, negotiation processes, and life skill development. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 1(1), 72-88.

CBC News. (2012, October 24). 10 neighourhoods for most per capita crime in 2011. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/10-neighbourhoods-for-most-per-capita-crime-in-2011-1.1295873

City of Toronto. (2011). 2011 Neighbourhood demographic estimates: Regent Park. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/8ffd-72-Regent-Park.pdf

City of Toronto. (2016a). 2016 Neighbourhood profile: Regent Park. https://www.toronto.ca/ext/sdfa/Neighbourhood%20Profiles/pdf/2016/pdf1/cpa72.pdf

City of Toronto. (2016b). 2016 Neighbourhood profile: Moss Park. https://www.toronto.ca/ext/sdfa/Neighbourhood%20Profiles/pdf/2016/pdf1/cpa73.pdf

City of Toronto. (2016c). 2016 Neighbourhood profile: North St. James Town. https://www.toronto.ca/ext/sdfa/Neighbourhood%20Profiles/pdf/2016/pdf1/cpa74.pdf

City of Toronto. (2018). Youth employment [Council Issue Note]. https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/council/2018-council-issue-notes/torontos-economy/youth-employment/

Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as “positive development?” Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(3), 306-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723511417311

Coakley, J. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On cultural sensibilities and the great sport myth. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(4-5), 402-406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214538864

Coalter, F. (2015). Sport-for-change: Some thoughts from a skeptic. Social Inclusion, 3(3), 19-23. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i3.222

Collins, M., & Haudenhuyse, R. (2015). Social exclusion and austerity policies in England: The role of sports in a new area of social polarisation and inequality? Social Inclusion, 3(3), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i3.54

Covenant House Toronto (2019). About us. https://covenanthousetoronto.ca/about-us/

Cragg, S., Costas-Bradstreet, C., & Kinglsey, B. (2018). Inventory, literature review and recommendations for Canada’s Sport for Development initiatives. Report prepared for the Federal-Provincial/Territorial Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation Committee, Ottawa, Canada. https://sirc.ca/app/uploads/2019/12/final_report_sport_for_development_literature_review_and_recomendations_for_indicators.pdf

Danish, S. J., Forneris, T., & Wallace, I. (2005). Sports-based life skills programming in the schools. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 21(2), 41-62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J370v21n02_04

Darnell, S. C., Chawansky, M., Marchesseault, D., Holmes, M., & Hayhurst, L. (2018). The state of play: Critical sociological insights into recent “sport for development and peace” research. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(2), 133-151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216646762

Dhungana, I. S. (2012). St. James Town community needs assessment report. Toronto Centre for Community Learning and Development. http://test.tccld.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/StJamesTown_2011-12_CRNA.pdf

Diemer, M.A. (2009). Pathways to occupational attainment among poor youth of color: The role of sociopolitical development. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(1), 6-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000007309858

Dobbels, L., Voets, J., Marlier, M., De Waegeneer, E., & Willem, A. (2018). Why network structure and coordination matter: A social network analysis of sport for disadvantaged people. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(5), 572-593. https://doi.org/10.1.1177/1012690216666273

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2019). Restaurant cook near Toronto (ON): Prevailing wages [Trend analysis]. https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/wages-occupation/6251/22437

Fraser-Thomas, J. L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2005). Youth sport programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 10(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898042000334890

Geobey, S. (2013). The young and the jobless: Youth unemployment in Ontario. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Ontario%20Office/2013/09/Young_and_jobless_final3.pdf

Gould, D., & Carson, S. (2008). Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 58-78.

Government of Ontario. (2018). Labour market report, June 2018. https://www.ontario.ca/page/labour-market-report-june-2018

James, R. K. (2010). From “slum clearance” to “revitalisation”: Planning, expertise and moral regulation in Toronto’s Regent Park. Planning Perspectives, 25(1), 69-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430903421742

Jones, G. J., Edwards, M. B., Bocarro, J. N., Bunds, K. S., & Smith, J. W. (2017). An integrative review of sport-based youth development literature. Sport in Society, 20(1), 161-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1124569

Kershaw, P. (2017). CodeRed: Ontario is the second worst economy in Canada for younger generations. Generation Squeeze. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/gensqueeze/pages/136/attachments/original/1491359455/GS_CodeRed_ON_second_worst_economy_2017-04-04.pdf?1491359455

Kumbi, S. (2013). Welcome to Moss Park Neighbourhood wellbeing survey report. The Centre for Community Learning and Development. http://www.tccld.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/MossPark_2012-2013_CRNA-Sara.pdf

Lane, K. L., & Carter, E. W. (2006). Supporting transition-age youth with and at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders at the secondary level: A need for further inquiry. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14(2), 66-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/10634266060140020301

Liang, J., Ng, G. T., Tsui, M., Yan, M. C., & Lam, C. M. (2017). Youth unemployment: Implications for social work practice. Journal of Social Work, 17(5), 560-578. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316649357

Lyras, A., & Welty Peachy, J. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Management Review, 14(4), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.05.006

MacIntosh, E., Arellano, A., & Forneris, T. (2016). Exploring the community and external-agency partnership in sport-for-development programming. European Sport Management Quarterly, 16(1), 38-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2015.1092564

Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment & Teamsters Local Union 847. (2016). Collective agreement between Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment and Teamsters Local Union 847, July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2019. https://www.sdc.gov.on.ca/sites/mol/drs/ca/Arts%20Entertainment%20and%20Recreation/711-86789-19.pdf

Matsuba, M. K., Elder, G. J., Petrucci, F., & Marleau, T. (2008). Employment training for at-risk youth: A program evaluation focusing on changes in psychological well-being. Child and Youth Care Forum, 37(1), 15-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-007-9045-z

Mayhew, C., & Quinlan, M. (2002). Fordism in the fast food industry: Pervasive management control and occupational health and safety risks for young temporary workers. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24(3), 261-284.

MLSE LaunchPad. (2018/19). Membership registration records. [Unpublished raw data].

Modestino, A. S., & Paulsen, R. (2019, March 20). School’s out: How summer youth employment programs impact academic outcomes. Northeastern University. https://cssh.northeastern.edu/people/wp-content/uploads/sites/34/2019/05/2019-Modestino-and-Paulsen-Schools-Out-2.pdf

Mumcu, H. E., Karakullukçu, Ö. F., & Karakuş. (2019). Youth employment in the sports sector. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Dergisi, 11(18), 2649-2665. https://doi.org/10.26466/opus.535301.

NPower Canada. (n.d.). About. http://npowercanada.ca/about/

Petitpas, A. J., Cornelius, A. E., Van Raalte, J. L., & Jones, T. (2005). A framework for planning youth sport programs that foster psychosocial development. The Sport Psychologist, 19(1), 63-80. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.1.63.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2018). Youth employment index: Understanding how organizational impacts can drive systems change. https://www.pwc.com/ca/en/corporate-responsibility/publications/PwC-Youth-Employment-Index-Web-ENG.pdf

Ross, M., Anderson Moore, K., Murphy, K., Bateman, N., DeMand, A., & Sacks, V. (2018, October). Pathways to high-quality jobs for young adults. Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Brookings_Child-Trends_Pathways-for-High-Quality-Jobs-FINAL.pdf

Sabeel Rahman, K. (2018). Constructing and contesting structural inequality. Critical Analysis of Law, 5(1), 99-126.

Sack, M., & Allen, L. (2019, March). Connecting apprenticeships to the young people who need them most: The role of community-based organizations. Center for Apprenticeship and Work-Based Learning. https://jfforg-prod-prime.s3.amazonaws.com/media/documents/Connecting_RA_to_Youth_-_03-04-2019_-_FINAL.pdf

Santos-Brien, R. (2018). Activation measures for young people in vulnerable situations: Experience from the ground. (Catalogue no. KE-01-18-813-EN-N). European Commission. https://doi.org/10.2767/014727

Schulenkorf, N., Sherry, E., & Rowe, K. (2016). Sport-for-development: An integrated literature review. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 22-39. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0263.

Spaaij, R. Magee, J., & Jeanes, R. (2013). Urban youth, worklessness and sport: A comparison of sports-based employability programs in Rotterdam and Stoke-on-Trent. Urban Studies, 50(8), 1608-1624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012465132

Statistics Canada. (n.d.). Income of individuals by age group, sex and income source, Canada, provinces and selected census metropolitan areas. (Table 11-10-0239-01). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110023901

Statistics Canada. (2019, May 10). Labour force survey, April 2019. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/190510/dq190510a-eng.pdf?st=4q8VQUjv

St. Stephen’s Community House & Access Alliance (2016). Tired of the hustle: Youth voices on unemployment. https://www.sschto.ca/SSCH/storage/medialibrary/media/Youth%20Action/employment%20research/TiredoftheHustleReport.pdf

Svensson, P. G., & Woods, H. (2017). A systematic overview of sport for development and peace organisations. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(9), 36-48.

Turnnidge, J., Côté, J., & Hancock, D. J. (2014). Positive Youth Development from sport to life: Explicit or implicit transfer? Quest, 66(2), 203-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2013.867275

Walker, C. M. (2018). Developing workreadiness; a Glasgow housing association sports-based intervention. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(4-6), 350-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1580604

Walker, M., Hills, S., & Heere, B. (2017). Evaluating a socially responsible employment program: Beneficiary impacts and stakeholder perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1051-015-2801-3

Welty Peachey, J., Cohen, A., Shin, N., & Fusaro, B. (2018). Challenges and strategies of building and sustaining inter-organizational partnerships in sport for development and peace. Sport Management Review, 21(2), 160-175.

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W., Blom, L., Camiré, M., Hayden, L., & Darnell, S. (2017, November 20). Sport for development in the United States: A systematic review and comparative analysis. Laureus Foundation USA. https://www.laureususa.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Final-Report-by-Whitley-et-al.pdf

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., Camiré, M., Blom, L. C., Chawansky, M., Forde, S., Boutet, M., Borbee, A., & Darnell, S. C. (2018). A systematic review of sport for development interventions across six global cities. Sport Management Review, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.013

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., Camiré, M., Boutet, M., & Borbee, A. (2019). Sport-based youth development interventions in the United States: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6387-z

Zhang, T. C., Torres, E., & Jahromi, F. (2019). Well on the way: An exploratory study on occupational health in hospitality. International Journal of Hospitality Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102382