Tom Bergen1,2 Geoff Kira3, Anja Mizdrak1, Louise Signal1, Justin Richards2,3

1 Department of Public Health, University of Otago, New Zealand

2 Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, New Zealand

3 Te Hau Kori, Faculty of Health, Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka, New Zealand

Citation:

Bergen, T., Kira, G., Mizdrak, A., Signal, L. & Richards, J. (2025). Wellbeing for rangatahi: Enhancing the Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework through an Equity Lens. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

The Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework (SNZOF) details the contribution of the physical activity (PA) system to national wellbeing. However, it is unclear whether the SNZOF meets the needs of the country’s diverse populations. This paper aims to review the SNZOF to assess whether it adequately addresses wellbeing for Māori and Pacific rangatahi (young people aged 12-17). We conducted a literature search of wellbeing frameworks for these populations and compared it to the SNZOF to identify gaps. Three themes were then formed by comparing similar gaps identified across the compiled literature; 1) the depiction of PA contribution to national wellbeing in the SNZOF is not adequately holistic; 2) the role of culture is not clearly detailed; 3) population autonomy is not included as a long-term outcome. To address the identified gaps, we made three overarching recommendations for future iterations of the SNZOF; 1) acknowledge all domains of long-term wellbeing equally as part of a more holistic approach; 2) make culture an overarching principle to the entire framework; 3) apply systems thinking to embed autonomy as a long-term outcome. Enhancing the SNZOF has positive future implications for equity across diverse rangatahi populations, creating a robust PA system and improving national wellbeing.

NZ RANGATAHI WELLBEING AND INEQUITIES AMONG DIFFERENT POPULATIONS

Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) rangatahi defined as youth aged 12-17-years old of any ethnicity by Sport NZ (Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2021), face multiple significant and ongoing challenges to wellbeing and development. For example, when compared to other high-income countries worldwide, NZ has high rates of household poverty, noncommunicable diseases, mental health issues and suicide (Ministry of Health, 2021a; Stats New Zealand, 2020; United Nations, 2020). Additionally, rangatahi of minority sociodemographic backgrounds experience high levels of inequity and consequently less favourable wellbeing than rangatahi of the majority (Crengle et al., 2012).

Māori, the Indigenous inhabitants of NZ, have a higher proportion of youth compared to adults and other ethnicities (Stats New Zealand, 2023a). Māori experience more inequities compared to NZ Europeans (NZE), who make up the majority of the population (Moewaka Barnes & McCreanor, 2019). Māori culture conceptualises wellbeing in a collectivist, holistic way that emphasises connections to whenua (land), whakapapa (genealogy) and incorporates many interconnecting wellbeing domains such as wairua (spiritual) or whānau (family/social) health (Durie, 1994; Hillary Commission, 1998). NZ’s founding document Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi), promised equal rights and opportunities for Māori and NZE despite differing cultures and viewpoints (Orange, 1987). Nowadays, British colonisation processes, coupled with a failure to uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi commitments have created a Westernised system where wellbeing inequities exist between the Māori and NZE. For example on average, Māori live in lower socioeconomic areas and experience worse health outcomes than NZE (Kennedy, 2017; Lal et al., 2012).

The proportion of Pacific young people in NZ is also higher compared to adults and other ethnicities (Stats New Zealand, 2023b). NZ Pacific peoples are people of Pacific ethnicity who migrated to, or were born in, NZ. Pacific populations share many similar approaches to wellbeing as Māori, meaning that the Westernised system of NZ often conflicts with their understanding and state of wellbeing (Cammock et al., 2014; Matika et al., 2021). Pacific people also experience inequities similar to Māori, particularly regarding limitations in existing data collection practices and a lack of population specific policies nationwide (Ministry of Health, 2021b; New Zealand Government, 2019; Thomsen et al., 2018).

Given the high proportion of Māori and Pacific young people addressing inequities in wellbeing is urgently needed in NZ. This need is further exemplified under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of a Child (UNCRC) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), showing that NZ has an obligation to improve the wellbeing of all rangatahi regardless of their culture, sociodemographic status or ethnicity (MacPherson, 1989; United Nations, 2007). One strength-based approach to improving the wellbeing of NZ rangatahi is through the further development of the countries PA system.

Physical Activity and Wellbeing in NZ

Regular PA participation promotes a multifaceted array of benefits for people’s wellbeing including decreased non-communicable disease risk (Myers et al., 2015) and improvements in mental health (Bowe et al., 2019), or the social (O’Dea, 2003), and economic (Davis, 2010) environment. Additionally, PA benefits can extend to less commonly cited, but still important, holistic determinants of wellbeing such as improving the natural environment (Mizdrak et al., 2019) or people’s wairua (connection to spiritual dimensions) (Anderson & Pullen, 2013; Hillary Commission, 1998). Despite this, results from the national Active NZ young people’s survey reveal that 42% of children and youth are not meeting global PA guidelines of accumulating an average of at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity PA daily (Bull et al., 2020; Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2020; Wilson et al., 2022).

International frameworks such as the Global Action Plan for PA and the Commonwealth’s ‘Contribution of Sport to the Sustainable Development Goals’ exemplifies how PA can be associated with a plethora of positive behaviour and health changes that contribute to population wellbeing (Lindsey & Chapman, 2017; World Health Organization, 2018). However, country-specific frameworks that clearly outline the connection between effective PA promotion and subsequent wellbeing benefits are still limited (Richards et al., 2022).

NZ Rangatahi PA and Wellbeing: The Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework

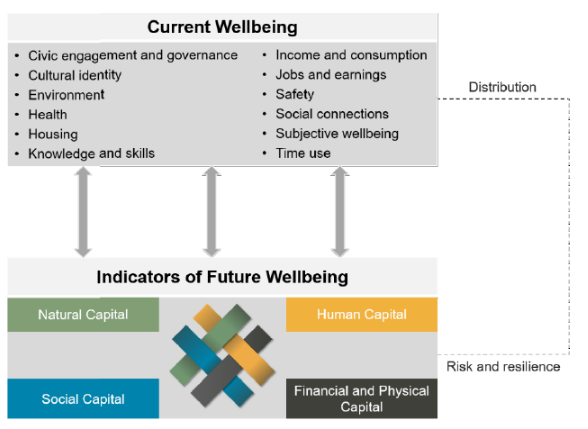

In 2019, the wellbeing agenda of the NZ Government was operationalised in the form of a national “Wellbeing Budget” that focussed on the importance of non-economic indicators of the status of the country and its population (New Zealand Treasury, 2019). To support this initiative, the Treasury created the Living Standards Framework (LSF), which was initially based on the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s wellbeing approach (New Zealand Treasury, 2018; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2020). The first iteration of the LSF comprised two major components: Current Wellbeing, and Indicators of Future Wellbeing (Figure 1). Together these attempted to conceptualise what mattered most to people and the resources that underpin the wellbeing of the population over the lifespan. Current wellbeing was characterised through 12 domains. Future wellbeing was indicated by the state of four national asset capitals: natural, social, human and financial/physical. These ‘capitals’ form the foundations that generate wellbeing both in the present and future (New Zealand Treasury, 2018). The LSF has been promoted by the NZ Government as a flexible guideline usable by a multitude of organisations and to sit alongside other sector and population-specific wellbeing frameworks (New Zealand Treasury, 2018).

Figure 1 – Complete Living Standards Framework 2018 version. Reproduced from New Zealand Treasury (2018)

Note: This figure depicts an earlier version of the New Zealand Living Standards Framework produced in 2018. It was made to conceptualise what mattered most to people and the resources that underpin the wellbeing of the population over the lifespan. From “Living Standards Framework: Background and Future Work,” by New Zealand Treasury, 2018, (https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-12/lsf-background-future-work.pdf).

Subsequently, Sport NZ, the country’s governing entity for PA, developed the Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework (SNZOF) (Figure 2) (Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2019b). It is based on an earlier iteration of the LSF illustrated in Figure 1. The purpose of this framework is to capture how the PA sector contributes to the wellbeing agenda of the government. It is underpinned by the socio-ecological model of health behaviour, which captures the determinants of PA behaviours that lead to subsequent wellbeing outcomes (Sallis et al., 2008). In addition to wellbeing outcomes, the SNZOF includes reference to key long-term outcomes for Sport NZ that culminate in improved PA participation and experiences. It also references Te Tiriti o Waitangi. However, since the SNZOF was formed with a predominantly Western view of wellbeing and limited conceptualisations from Indigenous perspectives, it is not a genuinely bi-cultural framework. Rather, Te Pākē o Ihi Aotearoa was developed autonomously alongside the SNZOF as a Māori framework purely from a Māori perspective. It holds mana orite (equal status) to the SNZOF, referring to Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2022). Further details of the development of the current SNZOF (and Te Pākē) and its application have been previously published (Richards et al., 2022).

Figure 2 – The current Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework. Reproduced from Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa (2019)

Note: This figure depicts the first version of the Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework in 2019, based on the 2018 iteration of the Living Standards Framework. The purpose of this framework is to capture how the PA sector contributes to the wellbeing agenda of the government. From “Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework,” by Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2019, (https://sportnz.org.nz/media/1144/sport-nz-outcomes-framework2.pdf).

Several limitations of the first iteration of the LSF have been identified by stakeholders representing various perspectives, e.g., Māori (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2019), Pacific (Thomsen et al., 2018), and young people (Dalziel et al., 2019). In response to these critiques, the LSF was later revised by the NZ Government (Figure 3) (New Zealand Treasury, 2021). However, to-date the SNZOF has not yet been updated in response to the revised LSF.

Figure 3 – Complete Living Standards Framework 2021 version. Reproduced from New Zealand Treasury (2021)

Note: This figure depicts the latest version of the New Zealand Living Standards Framework produced in 2021. The image displays the updates that have been made overtime to improve its function as a national framework. From “The Living Standards Framework 2021,” by New Zealand Treasury, 2021, (https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-10/tp-living-standards-framework-2021.pdf).

Therefore, the primary aim of this paper is to review the SNZOF to assess whether it adequately addresses wellbeing for Māori and Pacific rangatahi (young people aged 12-17). Our secondary aim was to identify any other areas of improvement to be made from the perspectives of the above groups that were not addressed in the revised LSF, but instead captured in other wellbeing literature.

METHOD

We conducted a literature search within Medline, Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science, SPORTdiscus and Google. Through our search we identified governmental reports, indexes, frameworks and development models that pertained to the wellbeing of young Māori and Pacific populations. Priority was given to literature that; 1) was created by members of the population of interest, 2) included reference to children or adolescent wellbeing, 3) captured the NZ context, and 4) explained wellbeing within similar contexts in developed countries. Additionally, we consulted with key stakeholders across the sector to direct us towards literature that met our criteria that may have been missed within the search.

We compared the compiled studies to the SNZOF and identified gaps when conceptualisations of Māori and Pacific rangatahi wellbeing literature were not adequately represented. To ensure we were capturing each unique conceptualisation of wellbeing and to avoid repetition, the gaps chosen only included the major wellbeing variables or dimensions that were explicitly stated in the chosen literature. We subsequently identified similarities between these gaps and created overlapping themes that broadly addressed the collective missing perspective of Māori and Pacific rangatahi wellbeing in the SNZOF. Finally, these similarities were synthesised into three themes that we surmised were pivotal for adding further equity to the SNZOF and aligning with the revised LSF.

RESULTS

While not an exhaustive list, some of the key Māori wellbeing frameworks and literature we drew knowledge from included; Te Hiringa Tamariki (UNICEF New Zealand, 2019), Te Whare Tapa Wha (Durie, 1994), Te Pae Māhutonga (Durie, 1999), He Ara Waiora (O’Connell et al., 2018), ‘Māori Cultural and Environmental specificity’ framework (Panelli & Tipa, 2007) and Māori perspective on LSF (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2019) and Whanau Haua (Hickey & Wilson, 2017). Key Pacific wellbeing frameworks and literature included; the Fonua Model (Tu’itahi, 2007), the Pacific perspective on the LSF (Thomsen et al., 2018), ‘Wellbeing through Pacific Children’s Eyes’ Framework (Dunlop-Bennett et al., 2019), Fonofale (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001), Pacific Wellbeing Outcome Framework (Ministry for Pacific Peoples, 2022), Ola Manuia Pacific Wellbeing and Action Plan (Ministry of Health, 2020) and the Advanced Frangipani Framework (Scheyvens et al., 2023).

The process and results of our literature search comparisons to the SNZOF and subsequent theme synthesis are summarised in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – The process for the synthesis of finding gaps in the Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework when compared to Māori and Pacific rangatahi wellbeing literature

Note: This figure depicts the process involved with synthesising Māori and Pacific wellbeing literature conceptualisations and noting whether these were adequately reflected in the Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework. Addressing the finalised themes were pivotal for adding further equity into the Outcomes Framework and aligning with the revised Living Standards Framework. This figure was created by the authors of this article.

The depiction of PA contribution to national wellbeing is not adequately holistic

The SNZOF suggests that the PA sector makes a secondary contribution to natural capital, which contrasts with the traditional ideals of Indigenous populations. Both Māori and Pacific research consistently depicts the importance of connection with the natural environment and how this has implications for all other aspects of wellbeing (Durie et al., 2010; New Zealand Treasury, 2018; Nunn et al., 2016; O’Connell et al., 2018). PA is similarly ingrained traditionally in the motivations and practices of Indigenous cultures and is effective at improving the natural environment in a variety of ways. For example, rangatahi are frequently taught about sustainability through traditional play such as how to respectfully traverse within water or gain knowledge of plant growth and care through gardening and foraging practices (Alcock & Ritchie, 2018; Panelli & Tipa, 2007). Therefore, ensuring that the SNZOF prioritises the connection between PA and the natural environment is an important consideration when considering both the preservation of nature and the subsequent wellbeing of the nation.

The SNZOF should also consider that PA plays a larger role than currently depicted in improving the financial and physical capital of the country when we consider the wellbeing needs of Māori and Pacific rangatahi populations. For example, physical cultural sites such as marae (Māori meeting grounds) and Pacific churches are important sites for PA and a range of other activities to occur for Māori and Pacific populations (Ministry for Pacific Peoples, 2022; UNICEF New Zealand, 2019). Therefore, investments that ensure cultural sites are PA-inclusive create an efficient way to incentivise PA for large portions of the population while simultaneously limiting national costs for the creation of other facilities such as gyms or recreation centres. Simultaneously, tailoring heavily frequented cultural sites towards better PA incentivisation reduces Māori and Pacific population’s travel costs and may readily cater to language and cultural needs, mitigating any additional costs associated with overcoming these barriers.

The role of culture is not clearly detailed

Culture has been defined as “the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs” (United Nations, 2001, p. 4). Culture is often depicted as synonymous with a population’s identity and interconnects with every other wellbeing dimension.

The SNZOF does not include culture as a domain of future wellbeing, which reflects the absence of any concepts tied to “cultural capital” within the first version of the LSF. However, cultural development is widely recognised as vital to the identity and knowledge of rangatahi and has been included in subsequent iterations of the LSF (New Zealand Treasury, 2021). Rangatahi are inherently a product of their culture, forming identities and values that are moulded by upbringing, whakapapa and connections between whānau and whenua (Moewaka Barnes & McCreanor, 2019). Furthermore, the importance and interconnected nature of culture can be seen through the Fonofale model of Pacific wellbeing (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001). Within the Fonofale Model, wellbeing is depicted as a house, with culture representing an overarching roof that interconnects with all other dimensions of wellbeing. Previous work also demonstrates how cultural development can occur through PA. For example, as shown in the ‘Te Whetū Rehua’ framework (Thompson, 2021), Māori experience additional wellbeing benefits when they are immersed in PA opportunities delivered in their own language and physical spaces of cultural significance.

Additionally, the importance of cultural identity to wellbeing has been widely recognised throughout many Māori and Pacific frameworks (Dalziel et al., 2019). For example, Te Pae Mahutonga exemplifies how a strong cultural identity comes from having secure accessibility to the world surrounding your culture such as language, cultural institutions and the natural environment (Durie, 1999). These accessibility needs change depending on the societal context an individual or group acts within. Therefore, we believe the SNZOF depiction of ‘cultural identity’ could more clearly represent the effect culture has on current wellbeing outcomes by further detailing the interaction between culture and wellbeing in the context of the PA sector. This is likely important for the future of the NZ PA sector, which has historically been shaped by non-Indigenous systems and structures regarding emphasis on solely economic value (Griffiths et al., 2023). Additionally, to improve rangatahi well-being, understanding different cultures’ PA preferences is important, but it must also be matched with a society that is equipped with adequate skills and resources for these preferences to flourish. This is reflected in the revised wellbeing outcome of “Cultural Capability and Belonging” in the most recent iteration of the LSF.

Population autonomy is not included as a long-term outcome

The SNZOF does not include reference to power or governance over decisions for their own people, a major challenge often faced by populations enduring inequities. For example, the Te Pae Māhutonga framework focuses on six interconnected elements of wellbeing and health promotion for Māori, one being Te Mana Whakahaere/autonomy (Durie, 1999; Hapeta et al., 2023). For this paper, we have adapted Durie’s definition of autonomy referring to populations being able to self-govern and have control over the priorities and decisions that affect them. Durie’s (1999) framework depicts the collectivist viewpoint of Māori culture, where balanced wellbeing is achieved, in this case, through both the PA and health system, guaranteeing tino rangatiratanga (autonomy over the design, delivery and monitoring of services that affect them). A key structural challenge to autonomy is that rangatahi involvement is often minimal in environments that make decisions regarding their wellbeing, such as local governments or young people-focused workplaces (Freeman & Aitken-Rose, 2005). Minimising the voice of Māori rangatahi in the PA system is subsequently detrimental to the nation as they have unique knowledge and perspectives that can uplift the mauri and wellbeing of the population (Page & Rona, 2021). Therefore, ensuring that the SNZOF promotes the creation of input opportunities for rangatahi across the PA system is vital for development and the enhancement of wider community wellbeing (Walker, 2014).

The SNZOF also depicts the contribution of PA to wellbeing as a one-way relationship and does not consider the reciprocal effect of current wellbeing on PA participation. It is important to note that the SNZOF never originally intended to capture causal loops and reverse causation, which is a key limitation of linear logic models (Remler & Van Ryzin, 2021). However, promoting autonomy means that the aspirations of each population must be considered when designing PA initiatives to enhance current wellbeing. Importantly, failure to afford autonomy and engage the relevant population in the development of PA initiatives has the potential to do harm rather than promote wellbeing. For example, some previous work has shown how Pacific rangatahi find purpose in prioritising caring for the whole whānau over their own individualised needs (Dunlop-Bennett et al., 2019). Consequently, Pacific rangatahi often put a lot of time into aiding their whānau, and prioritising their health and wellbeing due to the existing inequities they experience (Ministry of Health, 2021b; New Zealand Government, 2019; Thomsen et al., 2018). However, the potential overall wellbeing implications of displacing other leisure-time activities with PA are not accounted for in the current SNZOF. Specifically, the current SNZOF indicates that an increase in the proportion of leisure time spent being physically active has a positive impact on wellbeing. However, this perspective fails to capture the wellbeing detriments many Pacific rangatahi could experience due to PA taking them away from their caretaker roles (Thomsen et al., 2018).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that there are gaps within the SNZOF that limit its effectiveness in detailing how the PA system can improve NZ Māori and Pacific rangatahi wellbeing. This discussion explores recommendations that could be incorporated into a future SNZOF update, aligning it more closely to the latest iterations of the LSF and improving equity considerations.

Recommendation 1: Acknowledge all domains of long-term wellbeing equally as part of a more holistic approach

Future iterations of the SNZOF should exemplify how natural and financial capital are outcomes of equal magnitude to social and human capital to capture the holistic contribution of PA to the wellbeing of rangatahi. Visually, capitals appear to be individualised and separated from each other into boxes despite there being evidence of interconnection between levels. For example, facilitating simple, shared access to bicycles for rangatahi may likely improve their financial/physical capital (Molina-García et al., 2024). However, this financial/physical capital must interconnect with human capital, such as the skill to ride that bicycle to maximise positive wellbeing change (van Hoef et al., 2022). Therefore, we suggest a visual overhaul of the SNZOF, where all capitals as represented as equally important and stand within a single shape, interwoven with the other sections of the framework rather than standing alone. Accomplishing this removes the implication that PA contributions are siloed to one capital at a time and displays a more holistic impact of rangatahi PA engagement on wellbeing. Furthermore, the updated 2021 LSF has replaced the concept of ‘capital stocks’ with “wealth” to describe the assets available to the nation to influence wellbeing (New Zealand Treasury, 2021). The SNZOF should also adopt this change, as we believe it more accurately encompasses a move away from more historic economic definitions (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2020). Instead, usage of the word ‘wealth’ will clearly present a wider array of pathways in which PA can influence our national assets and expand the nation’s knowledge on how we must be flexible and holistic to achieve positive wellbeing across many different populations.

Recommendation 2: Make culture an overarching principle of the entire framework

Future iterations should emphasise the importance of culture by incorporating the concept as an overarching value to the whole framework, mirroring what was included in the 2021 LSF (New Zealand Treasury, 2021). This ensures that each section of the SNZOF is encouraged to connect PA to the cultural lifestyles and values of rangatahi, therefore making PA more meaningful and beneficial to their wellbeing. For example, a greater understanding of culture may enhance current wellbeing in the ‘knowledge and skills’ domain if the delivery of physical education includes reference to the whakapapa (historical origins) of the PA being undertaken (Salter, 2002). Additionally, an overarching inclusion of culture would further emphasise the importance of ‘cultural vitality’ as a long-term outcome, incentivising more options for rangatahi to be active in a style that suits their population and lifestyle.

The SNZOF could also introduce cultural ‘wealth’ as a component of future wellbeing, which has been suggested in previous critiques of the LSF (Dalziel et al., 2019). A section and definition for cultural ‘wealth’ would ensure that users of the SNZOF learn the value of developing cultural resources for PA and vice versa, such as including language skills or promoting PA in culturally significant sites (Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2023). This emphasises that culture belongs to the population in which it develops and intersects across all other domains of future wellbeing “wealth”.

Finally, the wording and definition of ‘cultural identity’ as a domain of current wellbeing could be adjusted to be more inclusive of the wider effect of culture on rangatahi. The updated LSF uses the term ‘cultural capability and belonging’, which we believe is fitting for the context of the SNZOF (New Zealand Treasury, 2021). This new term extends beyond describing a sense of identity and refers to how PA can be used as a vehicle for continuously developing the cultural understanding of individuals and society. Developing a sense of belonging is also a very common goal for PA participation (Mazereel et al., 2021). Therefore, this factor could be utilised to incentivise rangatahi to be inclusive of cultures other than their own and ensure everyone has a positive experience of PA that enriches their wellbeing.

Recommendation 3: Apply systems thinking to embed autonomy as a long-term outcome

Future iterations of the SNZOF should ensure that long term outcomes include giving each population autonomy over PA system decisions that affect them. Making autonomy a long-term priority is important as it is a complex process for trust and genuine partnership to develop between government entities and locally led community groups. Additionally, enabling the autonomy of Māori population strengthens NZ on a national level by upholding Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations and further unifying our diverse populations (Hapeta et al., 2023). For rangatahi it also ensures that they have the capabilities, skills, and resources needed to be active in the way they want, which can lead to a greater increase in long-term PA adherence and wellbeing enhancement (James et al., 2018). Furthermore, shifting power within PA participation opportunities to the community promotes inclusiveness and development (Edwards, 2015), which is highly important to improving rangatahi wellbeing and the future capability of the nation.

The SNZOF would also benefit from further development of the “system” long-term outcome with articulation of the ‘systems thinking approach’ espoused by existing interventions for promoting Māori wellbeing (Heke et al., 2019). Heke et al. (2019) utilised a Māori approach that is congruent with systems thinking and involved working with community groups as equals to map out the holistic, interconnected pathways to achieving a wellbeing outcome. This approach could be transferred to people from any PA governing body, combining opinions from both experts and funders while maintaining cultural integrity and locally specific values to develop opportunities that are adapted to a community or population. This ‘systems thinking approach’ will also enable more detailed articulation of the SNZOF intermediate outcomes, identifying concrete avenues across the socio-ecological spectrum in which to positively influence PA participation. For example, interviews with gender-diverse rangatahi in specific schools have revealed sociocultural and policy-level factors that would likely not be captured otherwise such as a dislike of mandated uniforms for school PA (Storr et al., 2022). Additionally, the ‘systems thinking approach’ avoids the ‘one-way’ depiction of cause-and-effect in the current SNZOF, which we previously noted was a key limitation of linear logic models (Remler & Van Ryzin, 2021). Instead, it would identify feedback loops and two-way interactions between components and levels of the SNZOF.

Implications

Updating the content of the SNZOF is important for addressing the priorities identified in the Sport NZ Strategic Direction for 2020-2032, including the promotion of a multicultural PA system (Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2020). An equity focus is vital for continuing the Sport NZ cultural journey and upholding its commitment to including Te Ao Māori perspectives. Additionally, addressing inequities at the early stages of framework development incentivises positive decision-making for all cultures and population groups. Historically, NZE viewpoints have been at the forefront of wellbeing and PA-related government frameworks. The inclusion of other populations will likely increase the number of avenues available for positive PA behaviour promotion.

Focusing on the way rangatahi engage in PA is important for all developed countries to ensure sustained participation over time. Rangatahi are at a vulnerable age where independence, lifelong habits and stricter time priorities start to develop (Viner et al., 2012). Key components of the SNZOF related to this factor are the intermediate outcomes, which reiterate principles of the socio-ecological model. Further enhancing this section with systems thinking would improve the articulation of how to promote equitable PA-specific behaviour change for all rangatahi. Contributions from all rangatahi to this process will result in practical and enjoyable PA opportunities that support behaviour change that is more likely to be sustained into adulthood (Fairclough et al., 2002).

Additionally, our suggestions for updating the SNZOF should improve the human rights of rangatahi as depicted in the UNCRC. Examples of this include promoting PA opportunities that benefit and relate to all rangatahi (article 29) and increasing the input rangatahi have in matters that pertain to them (article 12) (MacPherson, 1989). Furthermore, we have considered the rights of Indigenous rangatahi according to UNDRIP. For example, we applied a multicultural approach that promotes diverse and culturally specific interventions that are focused on the needs of Indigenous rangatahi (article 21) (United Nations, 2007).

The NZ Government has a commitment to improving wellbeing and youth development (New Zealand Government, 2019; New Zealand Treasury, 2019). Therefore, embedding equity into the SNZOF has flow-on effects that create a more robust channel for government funding and policy that prioritises PA as a vehicle for improving the wellbeing of the nation. This also strengthens our commitment to addressing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) (Lindsey & Chapman, 2017). For example, SDGs 10, 13 and 17 are improved through 1) the promotion of a more inclusive society, 2) caring more for nature through Indigenous teachings, 3) promoting worldwide collaboration and comparison (i.e. alignment of the SNZOF with the LSF and OECD wellbeing frameworks).

Updating the SNZOF could also serve as a template to promote an equity focus for existing, international and global PA agendas and goals. For example, the SNZOF would provide avenues for addressing a previously stated weakness of the SDGs, which is the challenge of implementation in local contexts and populations (Spaaij & Jeanes, 2013). Separately, a specific concern of the Global Action Plan for PA is to improve participation of the least physically active populations, which are often the people experiencing the most inequity more broadly (action 3.5, page 84) (World Health Organization, 2018). Therefore, our recommendations represent a commitment to improving worldwide PA participation by exemplifying transferrable methods in critiquing national PA systems. Particularly, whether these systems address entrenched inequities found both in minority or Indigenous populations and young people broadly.

Limitations

The lack of wellbeing literature on Pacific populations limited the wider perspective that we, as authors, could provide to this paper. Comprehensive approaches to capturing quality information and data from this group are still under development and it is critical that Pacific peoples are engaged in this process (Ministry of Health, 2020; Murray & Loveless, 2021). The scarcity of Pacific PA literature may also point to the inequities of development and access for Pacific scholars (Movono et al., 2021). In the interim, we formed the best evidence-based recommendations possible given the available literature and the make-up of our research team.

Furthermore, this paper misses the perspectives of specific rangatahi populations facing PA inequities such as Asian New Zealanders (Pringle & Liu, 2023), females and disabled people (Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa, 2019a). There may be additional modifications needed to conceptualise PA and wellbeing in other population groups experiencing inequities. However, these were outside of the scope of the paper. Future work could identify other frameworks focusing on different population groups that are relevant to wellbeing or PA participation and could also be incorporated into the SNZOF.

Finally, a limitation of our study was the predominantly literature-based analysis that we used to critique the SNZOF. Hearing directly from Māori and Pacific rangatahi would add depth to this analysis. Additionally, academic frameworks may not always provide the sector-specific application of knowledge needed to make practical adjustments of the SNZOF. Wellbeing is an inherently broad concept that cannot be comprehensively conceptualised solely in single publications or in-the-field examples (King et al., 2018). Therefore, future work may combine population-specific feedback, academic literature, and government frameworks to form the basis of critique for future iterations of the SNZOF.

CONCLUSION

The SNZOF is in a strong position to stimulate national wellbeing gains through the improvement of our PA system, particularly for populations experiencing inequities, such as Māori and Pacific rangatahi. This paper argues that equity focused changes are needed to enhance its effectiveness. An updated SNZOF would show a more holistic set of PA contributions to wellbeing, further detail the role of culture, and prioritise population autonomy. We recommend that these suggestions are applied to the SNZOF in future updates, incentivising equitable decisions in the promotion of PA and wellbeing for all rangatahi. Further investigation is also warranted into exploring the role of PA across different sectors to ensure that the NZ PA system has every avenue available to influence both equity-based policy and national wellbeing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

The PhD of T.B. is funded by Sport NZ, the lead government agency for physical activity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank advisors and stakeholders from the University of Otago, Victoria University of Wellington and Sport NZ Ihi Aotearoa for sharing their knowledge for the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Alcock, S., & Ritchie, J. (2018). Early childhood education in the outdoors in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-017-0009-y

Anderson, K. J., & Pullen, C. H. (2013). Physical activity with spiritual strategies intervention: A cluster randomized trial with older African American women. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 6(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20121203-01

Bowe, A. K., Owens, M., Codd, M. B., Lawlor, B. A., & Glynn, R. W. (2019). Physical activity and mental health in an Irish population. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 188(2), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1863-5

Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J. P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., Dipietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

Cammock, R. D., Derrett, S., & Sopoaga, F. (2014). An assessment of an outcome of injury questionnaire using a Pacific model of health and wellbeing. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online), 127(1388), 1–10.

Crengle, S., Robinson, E., Ameratunga, S., Clark, T., & Raphael, D. (2012). Ethnic discrimination prevalence and associations with health outcomes: Data from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of secondary school students in New Zealand. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-45

Dalziel, P., Saunders, C., & Savage, C. (2019). Culture, Wellbeing and the Living Standards Framework. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-06/dp19-02-culture-wellbeing-lsf_2.pdf

Davis, A. (2010). Value for Money: An Economic Assessment of Investment in Walking and Cycling. Analysis, March. https://bikehub.ca/sites/default/files/valueformoneyaneconomicassessmentofinvestmentinw.pdf

Dunlop-Bennett, E., Bryant-Tokalau, J., & Dowell, A. (2019). When you ask the fish: Child wellbeing through the eyes of Samoan children. International Journal of Wellbeing, 9(4), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v9i4.1005

Durie, M. (1994). Maori health perspectives (pp. 67–81). Whaiora-Māori Health Development. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

Durie, M. (1999). Te Pae Mahutonga – A Model For Māori Health Promotion. https://www.cph.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/TePaeMahutonga.pdf

Durie, M., Cooper, R., Grennell, D., Snively, S., & Tuaine, N. (2010). Whānau Ora: Report of the taskforce on whānau-centred initiatives. In Ministry of Social Development: Wellington. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/planning-strategy/whanau-ora/whanau-ora-taskforce-report.pdf

Edwards, M. B. (2015). The role of sport in community capacity building: An examination of sport for development research and practice. Sport Management Review, 18(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.08.008

Fairclough, S., Stratton, G., & Baldwin, G. (2002). The Contribution of Secondary School Physical Education to Lifetime Physical Activity. European Physical Education Review, 8(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X020081005

Freeman, C., & Aitken-Rose, E. (2005). Voices of youth: Planning projects with children and young people in New Zealand local government. Town Planning Review, 76(4), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.76.4.2

Griffiths, K., Davies, L., Savage, C., Shelling, M., Dalziel, P., Christy, E., & Thorby, R. (2023). The Value of Recreational Physical Activity in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Scoping Review of Evidence and Implications for Social Value Measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042906

Hapeta, J., Palmer, F., Stewart-Withers, R., & Morgan, H. (2023). Te Mana Whakahaere: COVID-19 And Resetting Sport in Aotearoa New Zealand BT – Sport and Physical Culture in Global Pandemic Times: COVID Assemblages (D. L. Andrews, H. Thorpe, & J. I. Newman (eds.); pp. 471–494). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14387-8_19

Heke, I., Rees, D., Swinburn, B., Waititi, R. T., & Stewart, A. (2019). Systems Thinking and indigenous systems: native contributions to obesity prevention. AlterNative, 15(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118806383

Hickey, H., & Wilson, D. (2017). Reframing disability from an indigenous perspective. MAI Journal, 6(1), 82–94. https://doi.org.10.20507/MAIJournal.2017.6.1.7

Hillary Commission. (1998). Taskforce Report on Mäori Sport. Wellington: Hillary Commission. https://natlib-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?vid=NLNZ&docid=NLNZ_ALMA21220640970002836&context=L&search_scope=NLNZ

James, M., Todd, C., Scott, S., Stratton, G., McCoubrey, S., Christian, D., Halcox, J., Audrey, S., Ellins, E., Anderson, S., Copp, I., & Brophy, S. (2018). Teenage recommendations to improve physical activity for their age group: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5274-3

Kennedy, M. (2017). Maori Economic Inequality: Reading Outside Our Comfort Zone. Interventions, 19(7), 1011–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2017.1401948

King, A., Huseynli, G., & Macgibbon, N. (2018). Discussion Paper: Wellbeing Frameworks for the Treasury (18/01). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/205374/1/dp18-01.pdf

Lal, A., Moodie, M., Ashton, T., Siahpush, M., & Swinburn, B. (2012). Health care and lost productivity costs of overweight and obesity in New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36(6), 550–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00931.x

Lindsey, I., & Chapman, T. (2017). Enhancing the contribution of sport to the sustainable development goals. Commonwealth Secretariat. https://www.sportanddev.org/sites/default/files/downloads/enhancing_the_contribution_of_sport_to_the_sustainable_development_goals_.pdf

MacPherson, S. (1989). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In Social Policy & Administration (Vol. 23, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.1989.tb00500.x

Matika, C. M., Manuela, S., Houkamau, C. A., & Sibley, C. G. (2021). Māori and Pasifika language, identity, and wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Kotuitui, 16(2), 396–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2021.1900298

Mazereel, V., Vansteelandt, K., Menne-Lothmann, C., Decoster, J., Derom, C., Thiery, E., Rutten, B. P. F., Jacobs, N., van Os, J., Wichers, M., De Hert, M., Vancampfort, D., & van Winkel, R. (2021). The complex and dynamic interplay between self-esteem, belongingness and physical activity in daily life: An experience sampling study in adolescence and young adulthood. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 21, 100413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2021.100413

Ministry for Pacific Peoples. (2022). Pacific Wellbeing Outcome Framework. https://www.mpp.govt.nz/assets/Reports/Pacific-Wellbeing-Strategy-2022/Pacific-Wellbeing-Outcomes-Framework-Booklet.pdf

Ministry of Health. (2020). Ola Manuia Pasific Wellbeing and Action Plan. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/ola_manuia-phwap-22june.pdf

Ministry of Health. (2021a). New Zealand Health Survey Key Results. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2020-21-new-zealand-health-survey

Ministry of Health. (2021b). Obesity Statistics. https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/health-statistics-and-data-sets/obesity-statistics

Mizdrak, A., Blakely, T., Cleghorn, C. L., & Cobiac, L. J. (2019). Potential of active transport to improve health, reduce healthcare costs, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions: A modelling study. PLoS ONE, 14(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219316

Moewaka Barnes, H., & McCreanor, T. (2019). Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(sup1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439

Molina-García, J., Queralt, A., Flaherty, C., García Bengoechea, E., & Mandic, S. (2024). Correlates of the intention to use a bike library system among New Zealand adolescents from different settlement types. Journal of Transport and Health, 34(November 2023), 101740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2023.101740

Movono, A., Carr, A., Hughes, E., Hapeta, J., Scheyvens, R., & Stewart‑Withers, R. (2021). Indigenous scholars struggle to be heard in the mainstream. Here’s how journal editors and reviewers can help Online. In The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/indigenous-scholars-struggle-to-be-heard-in-the-mainstream-heres-how-journal-editors-and-reviewers-can-help-157860

Murray, S., & Loveless, R. (2021). Disability, the Living Standards Framework and Wellbeing. Policy Quarterly, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v17i1.6732

Myers, J., McAuley, P., Lavie, C. J., Despres, J. P., Arena, R., & Kokkinos, P. (2015). Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness as Major Markers of Cardiovascular Risk: Their Independent and Interwoven Importance to Health Status. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 57(4), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2014.09.011

New Zealand Government. (2019). Child Youth and Wellbeing Strategy. https://childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-08/strategy-on-a-page-child-youth-wellbeing-Sept-2019.pdf

New Zealand Treasury. (2018). Living Standards Framework: Background and Future Work. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-12/lsf-background-future-work.pdf

New Zealand Treasury. (2019). NZ Wellbeing Budget. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-06/b19-wellbeing-budget.pdf

New Zealand Treasury. (2021). The Living Standards Framework 2021. 2021(October), 1–64. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-10/tp-living-standards-framework-2021.pdf

Nunn, P. D., Mulgrew, K., Scott-Parker, B., Hine, D. W., Marks, A. D. G., Mahar, D., & Maebuta, J. (2016). Spirituality and attitudes towards Nature in the Pacific Islands: insights for enabling climate-change adaptation. Climatic Change, 136(3–4), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1646-9

O’Connell, E., Greenaway, T., Moeke, T., & McMeeking, S. (2018). He Ara Waiora/A pathway towards wellbeing. Exploring Te Ao Māori perspectives on the Living Standards Framework for the Tax Working Group. New Zealand Treasury Discussion Paper. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/205384/1/dp18-11.pdf

O’Dea, J. A. (2003). Why do kids eat healthful food? Perceived benefits of and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among children and adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(4), 497–501. https://doi.org/10.1053/jada.2003.50064

Orange, C. (1987). The Treaty of Waitangi. In The Treaty of Waitangi (pp. 32–59). Bridget Williams Books Ltd;.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2020). How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-Being. https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

Page, C., & Rona, S. (2021). Kia Manaaki te Tangata: Rangatahi Māori Perspectives on Their Rights as Indigenous Youth to Whānau Ora and Collective Wellbeing. International Journal of Student Voice, 7(1).

Panelli, R., & Tipa, G. (2007). Placing well-being: A Māori case study of cultural and environmental specificity. EcoHealth, 4(4), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-007-0133-1

Pringle, R., & Liu, L. (2023). Mainland Chinese first-generation immigrants and New Zealanders’ views on sport participation, race/ethnicity and the body: Does sport participation enhance cultural understandings? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 58(4), 725–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902231156278

Pulotu-Endemann, F. K. (2001). A Pacific model of health: The Fonofale model. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/actionpoint/pages/437/attachments/original/1534408956/Fonofalemodelexplanation.pdf?1534408956

Remler, D. K., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2021). Research methods in practice: Strategies for description and causation. Sage Publications.

Richards, J., Hamilton, A., & McEwen, H. (2022). Repositioning sport as an innovation within national policy. Social Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Sport for Development and Peace, 215–227. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003212744-22

Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. B. (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. In Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice, 4th ed. (pp. 465–485). Jossey-Bass.

Salter, G. (2002). Locating “Maori Movement” in mainstream physical education: curriculum, pedagogy and cultural context. Journal of Physical Education New Zealand, 35(1), 34–44.

Scheyvens, R., Movono, A., & Auckram, J. (2023). Enhanced wellbeing of Pacific Island peoples during the pandemic? A qualitative analysis using the Advanced Frangipani Framework. International Journal of Wellbeing, 13(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v13i1.2539

Spaaij, R., & Jeanes, R. (2013). Education for social change? A Freirean critique of sport for development and peace. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 18(4), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.690378

Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa. (2019a). Active NZ Survey. https://sportnz.org.nz/media/3639/active-nz-year-3-main-report-final.pdf

Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa. (2019b). Sport New Zealand Outcomes Framework. https://sportnz.org.nz/media/1144/sport-nz-outcomes-framework2.pdf

Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa. (2020). Every Body Active. 1–40. https://sportnz.org.nz/media/1160/strategy-doc-201219.pdf

Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa. (2021). Active NZ Spotlight on Rangatahi Report. https://sportnz.org.nz/media/131pp1kx/active-nz-spotlight-on-rangatahi_june-2021.pdf

Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa. (2022). Te Pākē o Ihi Aotearoa. https://sportnz.org.nz/media/5028/te-pa-ke-o-ihi-aotearoa-april-2022.pdf

Sport New Zealand Ihi Aotearoa. (2023). Te Whetū Rehua. https://sportnz.org.nz/kaupapa-maori/e-tu-maori/te-whetu-rehua/

Stats New Zealand. (2020). New Zealand Child Poverty Statistics 2020. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/child-poverty-statistics-year-ended-june-2020

Stats New Zealand. (2023a). Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2023. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2023/

Stats New Zealand. (2023b). Pacific housing: People, place, and wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/pacific-housing-people-place-and-wellbeing-in-aotearoa-new-zealand/

Storr, R., Nicholas, L., Robinson, K., & Davies, C. (2022). ‘Game to play?’: barriers and facilitators to sexuality and gender diverse young people’s participation in sport and physical activity. Sport, Education and Society, 27(5), 604–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1897561

Te Puni Kōkiri. (2019). The Treasury Discussion Paper 19/01 – An Indigenous Approach to the Living Standards Framework. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-01/dp19-01.pdf

Thompson, V. (2021). Te Whetū Rehua Review Report (Issue August). https://sportnz.org.nz/media/4807/2021-te-whetu-rehua-review-report.pdf

Thomsen, S., Tavita, J., & Levi-Teu, Z. (2018). A Pacific perspective on the living standards framework and wellbeing (Issue 18/09). New Zealand Treasury Discussion Paper. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-08/dp18-09.pdf

Tu’itahi, S. (2007). Fonua Model. Health Promotion Forum: Hauora. https://hpfnz.org.nz/pacific-health-promotion/pacific-health-models/

UNICEF New Zealand. (2019). Te Hiringa Tamariki. May. https://downloads.ctfassets.net/7khjx3c731kq/1Wjs9ANGNkRV6vLkPTefwn/e87fdf7a38ed9f2e6084cb9e812ae8b4/Te_Hiringa_Tamariki_Report_Design_20_7_19_UPDATE_without_back_logo_box.pdf

United Nations. (2001). Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127162

United Nations. (2007). The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In Austrian Review of International and European Law Online. https://doi.org/10.1163/15736512-90000006a

United Nations. (2020). Worlds of Influence: Understanding what shapes child well-being in rich countries. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/1816/file/UNICEF-Report-Card-16-Worlds-of-Influence-EN.pdf

van Hoef, T., Kerr, S., Roth, R., Brenni, C., & Endes, K. (2022). Effects of a cycling intervention on adolescents cycling skills. Journal of Transport and Health, 25, 101345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2022.101345

Viner, R. M., Ozer, E. M., Denny, S., Marmot, M., Resnick, M., Fatusi, A., & Currie, C. (2012). Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60149-4

Walker, S. (2014). Targeting teenagers. Australasian Parks and Leisure, 17(2), 43–45.

Wilson, O. W. A., Ikeda, E., Hinckson, E., Mandic, S., Richards, J., Duncan, S., Kira, G., Maddison, R., Meredith-Jones, K., Chisholm, L., Williams, L., & Smith, M. (2022). Results from Aotearoa New Zealand’s 2022 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth: A call to address inequities in health-promoting activities. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness, 21(1), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2022.10.009

World Health Organization. (2018). Global Action Plan 2018-2030. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf