Anna Farello1, Lindsey C. Blom1, Thalia Mulvihill1, Jennifer Erickson1

1 Ball State University, USA

Citation:

Farello, A., Blom, L., Mulvihill, T. & Erickson, J. (2019). “Understanding female youth refugees’ experiences in sport and physical education through the self-determination theory.” Journal of Sport for Development, 7(13), 55-72. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

As female youth from refugee backgrounds are forced to migrate and resettle, they face unique challenges not often addressed by their host community. Participating in physical activity (PA), however, may pave a pathway to healthy resettlement. Nine Burmese females from refugee backgrounds participated in semistructured interviews and discussed their experiences in sport and physical education and how those experiences relate to their sense of belonging, autonomy, and relationships, as well as their ability to adapt. Participants then completed a photovoice task where they photographed highlights and challenges they have faced in PA. Photographs were analyzed and discussed in a follow-up interview. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis. Resulting dimensions such as sport incompetence, growth mindset, importance of autonomy and choice, and desired peer relationships support Ryan and Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory. Practical implications for PE teachers, coaches, and school administrators are discussed. These results inform school districts of potential barriers and future interventions that could help this population better resettle and encourage participation in sports and physical activity.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout 2019, nearly 26 million refugees worldwide have been displaced from their home countries, with only 92,000 officially resettled (U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, 2019). Refugees are “forcibly relocated from their origin country, arriving in their host country after internal displacement, migration through other countries, or living in refugee camps for significant periods amidst hazardous conditions” (Edge et al., 2014, p. 35). Among other things, refugees can experience and/or witness violence, torture, injury, imprisonment, and homelessness (Hadfield et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2016; Tribe, 2005). Perhaps the most vulnerable group of refugees is youth, who represent the largest percentage of forced migrations (U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, 2019). This population must cope with identity disruption (Keddie, 2011), making social connections with peers and adults (Olliff, 2008; Palmer, 2009), learning a new language (Shakya et al., 2010), and adapting to a new school system (Prior & Niesz, 2013). Because these obstacles can threaten their overall well-being, practitioners and researchers are looking for strategies and solutions that could mitigate these concerns. The field of Sport for Development and Peace (SDP) suggests participation in physical activity (PA) and sport may be a strategy, especially for female youth (Collison et al., 2017; Stura, 2019; Whitley et al., 2016; Whitley & Gould, 2011). Therefore, the purpose of the present research was to better understand the role of PA and sport in the resettlement of female youth with refugee backgrounds.

Research in SDP and other fields suggest PA, exercise, and/or sport are potential ways individuals from refugee backgrounds can cope with various resettlement challenges (Anderson et al., 2019; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Olliff, 2008; Palmer, 2009; Robinson et al., 2019; Whitley et al., 2016). Worldwide, grassroots SDP programs are growing in numbers and quality (Svensson & Woods, 2017). However, programs targeting displaced youth are less common (Ha & Lyras, 2013; Ubaidulloev, 2018; U.N. Refugee Agency, 2019). Thus, organized sport could improve its outreach to involve more youth from refugee backgrounds, as sport and general PA could be helpful in the resettlement process.

Further, many of the benefits of sport, exercise, and PA are similar to the factors that help refugees better resettle in their host country, including enhanced autonomy, a sense of belonging, connections with peers and adults, and resilience. Autonomy, for instance, can buffer against negative psychological outcomes (Bean et al., 2014; Edge et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2016; Pieloch et al., 2016) and can be fostered by autonomy-supportive coaches and PE teachers (Bean et al., 2014; Beni et al., 2017; Elbe et al., 2018). Feeling a sense of belonging also aids youths’ resettlement (Hadfield et al., 2017; Mohammadi, 2019) and could be a product of group PA participation (Block & Gibbs, 2017; Dukic et al., 2017; Nathan et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2019; Whitley et al., 2016). Additionally, social support from peers and important adults (e.g., coaches, teachers, parents) is crucial for youth refugees’ psychological well-being and adaptation (Hadfield et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2016). In sport, supportive environments that accept youth refugees and their culture are more conducive to positive PA experiences (Dagkas et al., 2011; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Whitley et al., 2016). Finally, characteristics that refugees often exhibit during migration, such as resilience, may be helpful for effective resettlement (Jani et al., 2016; Pieloch et al., 2016) and may result from regular PA or sport participation (Fader et al., 2019; Griciūtė, 2016; White & Bennie, 2015). The literature can be synthesized into a few components that connect PA to resettlement: autonomy, peer and adult relationships, and a sense of belonging.

However, these positive outcomes are far from guaranteed by simple sport or PA participation. Critical insights of sport as an empty signifier suggest sport has the power to positively influence and develop youth when it is programmed in a way that implicitly and explicitly fosters such values (Coakley, 2011; Coalter, 2015). Without proper attention to positive youth development, sport can elicit negative experiences such as social exclusion (Collison et al., 2017; McKay et al., 2019), increased stress (Merkel, 2013), and injuries (McKay et al., 2019; Merkel, 2013), causing youth to quit sports (Merkel, 2013; Aspen Institute Project Play, 2018). For youth from refugee backgrounds who are already less likely to play sports (O’Driscoll et al., 2014), programming is more important to help this population appropriately resettle (Anderson et al., 2019; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Robinson et al., 2019; Whitley et al., 2016). Bean and colleagues (2018) found sport programs offering more opportunities for athletes to enhance their autonomy and relatedness were rated as “high quality.” Similarly, refugee youth in a program based on the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility model expressed increased feelings of belonging and trusting relationships with adults since joining the program (Whitley et al., 2016). Asylum seekers in Australia reported similar sentiments about participating in their football program (Dukic et al., 2017; McDonald et al., 2019). Thus, youth may gain autonomy, peer and adult relationships, and/or a sense of belonging from sports programs, but they need to be properly designed to infuse such constructs. Ultimately, using PA as a means of healthily resettling relies on both the newcomers and the receiving country and community (Brenner & Kia-Keating, 2016; Spaaij, 2013; Stone, 2018). The collaboration between these two parties may be one solution for how individuals from refugee backgrounds can use sport to resettle effectively.

While all youth refugees may experience adversity as they migrate, female refugees confront additional challenges. Compared to males, they may have fewer opportunities to receive an education, are further behind in educational level (U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, 2019), and are limited in activities outside the home due to traditional gender roles and culture (Palmer, 2009; Robinson et al., 2019). Vulnerability and safety concerns often make mothers reluctant to allow their daughters to participate in community activities or after-school programs, thus restricting their autonomy and peer interactions (Caperchione et al., 2011; Palmer, 2009; Robinson et al., 2019). For these reasons, it is not surprising that SDP programs worldwide lack girls’ participation (Collison et al., 2017). The sport involvement of girls from refugee backgrounds is understudied, with research often focusing on boys (Dwyer & McCloskey, 2013; Elbe et al., 2018; Fader et al., 2019; Stura, 2019; Whitley et al., 2016). Consequently, girls may be at a disadvantage in the sport domain and should be given a voice.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The components of autonomy, peer and adult relationships, and a sense of belonging that connect physical activity to resettlement highlighted in this study align with Ryan and Deci’s (2000) theory of self-determination (SDT), originally developed to explain intrinsic motivation. The theory’s three main components are competence, autonomy, and relatedness. When an individual feels knowledgeable and capable in a specific area of her life, has the agency to act, and has peers and other important relationships, her psychological well-being is high. For refugee youth, autonomy is rare because parents are protective of their children in a new place (Palmer, 2009; Pieloch et al., 2016). Furthermore, they usually have little knowledge of their new culture, and language discrepancies make peer relatedness difficult (Hadfield et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2016). The apparent challenge in reaching self-determination makes SDT of particular interest to female youth from refugee backgrounds.

An additional foundation of this study was the use of photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997), a visual method that illuminates participants’ daily lives and their communities (Yam, 2017). It is especially effective in research with participants who have little money, power, or status (Dávila, 2014; Strack et al., 2004), such as youth with refugee backgrounds. Photovoice can aid youth in articulating thoughts and feelings through photographs and subsequently guide discussion (Strack et al., 2004).

Present Study

A currently understudied area is how refugee background female youth’s experiences in PA reflect intra- and interpersonal factors and how these factors might play a role in their school and community. A review by O’Driscoll and colleagues (2014) found only 12% of their studies focused on sport participation in migrant populations, while Ha and Lyras (2013) noted most resettlement studies have not investigated sport participation in youth from refugee backgrounds. More important, it is uncommon to ask youth, let alone those from refugee backgrounds, about their experiences and how they could be improved (Couch, 2007; Erden, 2017; Jeanes et al., 2015; Strack et al., 2004). Some researchers have called for a better understanding of the PA needs and preferences of youth immigrants and youth from refugee backgrounds, as well as the recognition of their complex, rich, and strengths-based narratives (Ryu & Tuvilla, 2018; Stodolska & Alexandris, 2004). Educational institutions facing increased numbers of immigrant and refugee youth would benefit from understanding how these individuals could better function in PA environments (Lleixà & Nieva, 2018; Şeker & Sirkeci, 2015). Communities with refugee populations may also benefit from understanding some barriers their youth face with PA so they can increase engagement.

The nature of the relationships between PA engagement and supportive factors for resettlement have been presented, which can help youth overcome such challenges and work toward self-determination and psychological well-being. Thus, the purpose of the present research was to better understand the role PA plays in the resettlement of female youth from refugee backgrounds. Two research questions guided a larger study, but only the first is presented: What are female youth refugees’ experiences in sport, physical activity, and/or physical education in relation to their sense of autonomy, relationships with peers and adults, and sense of belonging? This question was conceptualized using SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000), and explored through basic qualitative methodology, which focuses on understanding participants’ experiences, uses interviews to collect data, and presents findings as themes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Methods included an initial semistructured interview, a photovoice task, and a follow-up interview.

METHODS

Participants

This study focuses on girls from Burma, a country in Southeast Asia, who resettled in the United States. Burma is a diverse country with several ethnic groups, the largest being Burman, Chin, and Karen (Barron et al., 2007). Citizens commonly flee Burma due to human rights violations (Barron et al., 2007), religious persecution (Gibbens, 2017), and government repression (MacDonnell & Schmidt, 2012) to find safety in Thai refugee camps. Female youth were recruited via convenience sampling through a partnership with an urban school district in the Midwestern United States. An English as a nonnative language (ENL) coordinator was the main contact, as the school district asked for information to help their students from refugee backgrounds. As outlined by McLaughlin and Black-Hawkins (2004), a school-university partnership allows both parties to benefit from the research and requires communication and collaboration at important stages throughout the study. As such, the ENL coordinator aided the first author in identifying potential participants who met the following criteria: (a) had a refugee background; (b) had been in the United States for at least one year; and (c) were proficient English speakers. Because all potential participants preferred English to their native language and expressed themselves clearly, the authors felt an interpreter during interviews was unnecessary. Furthermore, these criteria were developed to facilitate an efficient data collection process so the school district could receive the results within the school year.

Nine female youth from refugee backgrounds participated, with an average age of 14.8 years (SD = 0.83). Eight were born in Thai refugee camps; the ninth was born in Burma but spent her formative years in a Malaysian refugee camp. Participants’ average length of time since resettlement was eight years (SD = 2.2) in the United States, and 6.9 years (SD = 3.1) specifically in the Midwest. The most common PAs reported were walking daily (n = 6), soccer (n = 4), and running (n = 3).

Instruments

The primary instrument in this qualitative study was the interviewer. A demographic form, semistructured interview guides for the initial and follow up interviews, and recording devices (i.e., digital audio recorders and digital cameras) were used. Three supporting researchers contributed to data analysis.

Interviewer. The interviewer and first author was a 23-year-old woman in her second year studying Sport and Exercise Psychology, with a minor in counseling, at a Midwestern university in the United States. Her history of participating in several organized sports led to her belief that PA is integral to one’s physical and psychological well-being. Furthermore, she has qualitative and quantitative research experience in positive youth development and sport for development and peace organizations, which have provided opportunities for her to see the power of sports when they are appropriately designed.

Demographic Form. A demographic form was distributed when participants met the first author for the initial interview. It asked for participants’ age, country of birth, number of years since resettlement, and types and frequency of PA in which she engaged.

Interview Guides. Two semistructured interview guides helped navigate the conversations while still allowing flexibility if a certain topic warranted probing questions. These guides aimed to situate the participant, rather than the interviewer, as the expert on her experiences (Dávila, 2014). The initial interview guide contained four parts. Part I asked simple, introductory questions that became more complex as rapport was built (Jacob & Furgerson, 2012). In part II, participants were asked what PA, exercise, and sport meant to them, and what role each played in her life. Part III questioned participants’ experiences in Physical Education (PE) class in school, the types of PA in which they engage during class, and how they would ideally structure PE. For part IV, participants reflected on the main differences between life in their refugee camp and their current community and how living in the United States had influenced their perceptions of PA, sport, and exercise. The final question explored what the girls believed would help them feel more successful (e.g., psychologically healthy, supported).

At the end of the initial interview, participants were given instructions on how to complete the photovoice process, which is a qualitative method that enhances dialogue through photographs (Wang & Burris, 1997). Participants were asked to take photos with the following guidelines: (a) up to 10 of people, places, and things representing challenges they have faced with PA, sport, and/or exercise; and (b) up to 10 photos of people, places, and things that represent highlights they have experienced with PA, sport, and/or exercise since moving to the Midwest.

Before starting the follow-up interview, participants shared relevant updates since the initial interview. The participant was then asked to retrospectively explain the meaning behind her photos using the SHOWeD method (Strack et al., 2004). This method asks photographers: “What do you see here? What is really happening here? How does this relate to our lives? Why does this situation, concern, or strength exist? and What can we do about it?”

Recording Devices. An Olympus DM-720 digital voice recorder was used to record interviews. For the photovoice task, participants received one KINGEAR High Definition Digital Camera for capturing photos related to PA barriers and highlights. The camera was returned to the first author after the follow-up interview.

Research Team. The research team consisted of the second author and three Masters-level students studying Sport & Exercise Psychology at a Midwestern university. All three students had experience working with youth in a sport setting and were actively conducting research either with youth or in PA. Before data analysis, the students were briefed on relevant literature about female youth from refugee backgrounds, this population’s reported engagement in PA, and details of the current study. The second author is a faculty member with an extensive background in positive youth development, sport for development, and sport for peace. She is well published in these domains and was integral to the entire research process. The other two authors are faculty members who reviewed the themes. One is an expert qualitative researcher, and the other has a strong background in working with and researching refugee populations.

Procedures

After obtaining approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board, recruitment began. Written parental consent forms in English were given to the school’s ENL coordinator who distributed them to potential participants and collected them if permission was granted. Because working with a vulnerable population warrants consent in multiple manners (Block et al., 2013; van Liempt & Bilger, 2012), consent was explained to participants verbally, in writing at a sixth-grade level, and with the ENL coordinator who relayed the process to potential participants. The first author then visited the school to speak to eligible participants about the study, answer questions, and begin building rapport. Completed parental consent forms were collected, and interested participants provided their contact information and a preferred interview time for the following week. Before collecting data, literature searches on Burmese culture were conducted to provide cultural context for the interviews and increase the interviewer’s awareness, as suggested by Dávila (2014).

The initial interviews were conducted either at the participant’s home (n = 5) or their high school (n = 4) during school hours. The initial meeting with the participant included five components: (a) written parental consent, if not previously collected, (b) verbal explanation, distribution, and collection of the participant’s written assent, (c) participant completion of the demographic form, (d) the interview, and (e) photovoice instructions. The goal of the initial interview was to gather information about the participant’s refugee experience, such as how they participate in PA, what their past and current experiences in PA have been like, and the easiest and toughest aspects of resettling in the United States. Member checking, a qualitative technique to ensure the accuracy of the information received, was utilized throughout both interviews (Thomas et al., 2010). To comply with core ethical principles, interviews were prefaced by assuring participants they only had to answer questions with which they were comfortable and to the extent with which they were comfortable (Block et al., 2013). The interviewer intermittently asked clarifying questions and paraphrased longer sections of their stories to confirm that information was accurate, thus increasing trustworthiness of the data.

Following the interview, the photovoice process was explained. The participant received a digital camera and was taught how to zoom, capture a photo, and charge the camera. She was then prompted to take up to 20 photos of highlights and challenges she has faced in PA before the follow-up interview, between one and two weeks later.

The goal of the follow-up interview was to discuss the content of the photos based on the questions listed previously (Strack et al., 2004). The digital camera was plugged into a laptop to enlarge the photos, which were analyzed chronologically. The final piece of both interviews thanked participants and asked if they would like to add, modify, or provide feedback on anything they had discussed (Dávila, 2014; van Liempt & Bilger, 2012). Both interviews were audio recorded then transcribed verbatim by hand. On completion of both interviews, participants chose a piece of sport equipment worth up to $15.

Research Design and Analysis

The data from this basic qualitative study (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015) was analyzed using thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998; Braun & Clarke, 2006). This approach allowed the research team to identify commonalities throughout the interviews and organize them into first-order themes, second-order themes, and dimensions (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Thomas et al., 2010). To understand the data more fully, participants’ experiences in PA and sport were examined within a sociocultural context, encompassing their relationships, autonomy, and sense of belonging.

The audio recordings from both sets of interviews were listened to multiple times (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012), then transcribed verbatim into Microsoft Word by the first author and her team of three female graduate students. Each team member transcribed two initial interviews. Though time constraints prevented participants from being included in the triangulation process, the first author clarified participants’ responses and member checked throughout the interviews to increase trustworthiness (Thomas et al., 2010).

The coding procedure mainly used a deductive approach. Self-determination theory guided the formation of the dimensions, while the subdimensions were created inductively. The first author merged her written observations (i.e., intonations or nonverbal cues) from the interviews with the transcriptions (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012). Any information related to the research question and constructs (i.e., peer relationships, adult relationships, autonomy, sense of belonging) was highlighted (Thomas et al., 2010) along with any other raw data that needed to be coded. Each team member read transcriptions from three participants (six interviews) multiple times to ensure comprehension and enhance credibility and trustworthiness. Then first-order themes were created based on highlighted content from the first author (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012; Thomas et al., 2010). These themes were clustered by conceptual similarity into 10 to 20 second-order themes (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012) before the first author merged the team member’s themes with the themes she had created separately.

To create the final dimensions and subdimensions, each second-order theme was written on an index card, which the research team and first author organized into piles by conceptual similarity (Thomas et al., 2010). All members agreed with the organization of the second-order themes before the resulting dimensions and subdimensions were triangulated with the second author to ensure credibility. The first author then identified raw data quotes exemplifying each subdimension.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This article addresses one of two research questions about

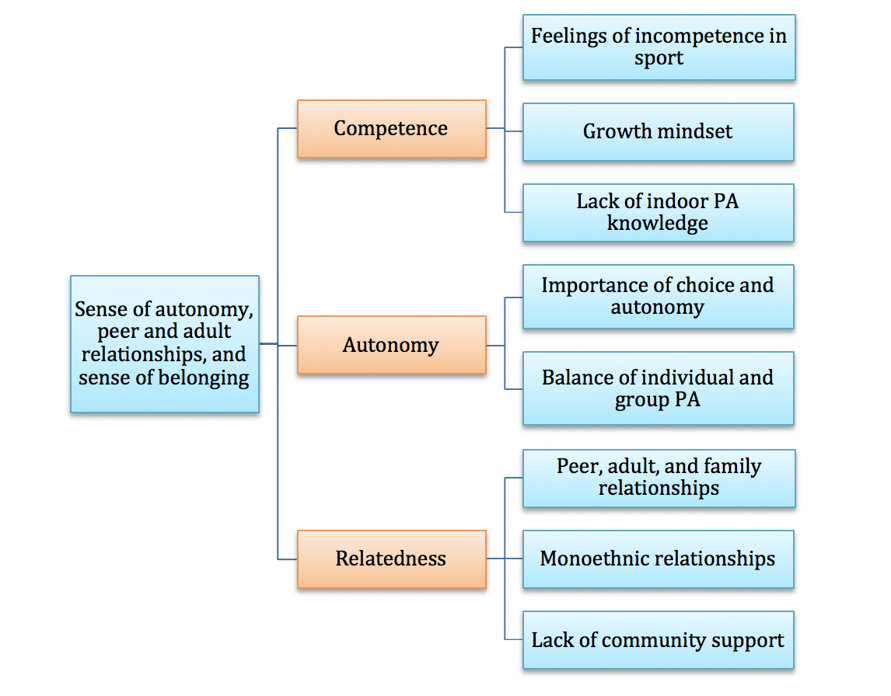

female youth refugees’ experiences in PA, exercise, and/or sport in relation to their autonomy, relationships with peers and adults, and sense of belonging. Data analysis was primarily deductive and secondarily inductive. The research team’s immersion into the data and extraction of commonalities from the perspective of a youth female refugee aided in the thematic analysis process. Specifically, three dimensions from SDT (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) and eight subdimensions (feelings of incompetence in sport; growth mindset; lack of indoor PA options and accessibility; importance of choice and autonomy; balance of individual and group PA; peer, adult, and family relationships; monoethnic relationships; and lack of community support) were identified (see comprehensive list in Figure 1 and quotes in Table 1).

Figure 1 – Summary of dimensions and subdimensions

Competence

The first component of SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000) is competence, or the ability to perform a certain task. This dimension resulted in three subdimensions: (a) feelings of incompetence in sport were connected to feelings of exclusion in school and in the community; (b) approaching PA opportunities with a growth mindset fostered competence; and (c) the lack of knowledge regarding indoor PA exercises and training also appeared to hinder the refugees’ ability to stay active during the winter season.

Table 1 – Verbatim extracts from interviews with participants

Feelings of incompetence in sport. Nearly every participant mentioned that not knowing how to participate in a specific sport or activity made her feel a sense of not belonging. One participant in particular said:

For physical [PE class], there are a lot of skillful people, not a lot of nice people when it comes to game. I make mistakes sometimes, and they say something that makes me want to be out of the team so I don’t—so I feel like I don’t fit in. (004-Initial)

In this case, the participant reported her classmates made rude comments if she made a mistake during PE class, which might discourage PA participation. Similarly, another participant stated that when playing volleyball in PE, “I’m not belong to it when I can’t serve because serve is the most important thing. Yeah. And when you don’t understand the score. . . . I feel like I’m not good at it so I’m not belong to it whenever this happen” (010-Initial). For these two girls, feeling incompetent in sport may relate to the differences between the popular sports available for youth in their home country and the United States, as well as the setting in which they are learning (Anderson et al., 2019). Sports such as volleyball, American football, and badminton played in PE are unfamiliar to them, so naturally they require more time to learn the rules, vocabulary, and sport-specific skills. This desire for competence in motor skills is consistent with Beni and colleagues’ (2017) link between meaningful PA experiences and feeling knowledgeable and capable of performing certain sport skills. Competence can be achieved through sport participation (Beni et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2019), especially in a conducive learning environment. For example, coaches and teachers could first introduce universal sports before culture-specific ones to young people from refugee backgrounds (Hertting & Karlefors, 2013). If the well-known sports are used as a basis of knowledge for future sport units in PE class, participants may feel more competent in their abilities and more included. Further, competence may emerge in sport settings that are health-focused (Anderson et al., 2019), culturally sensitive (Dagkas et al., 2011), and cater to participants’ needs (Anderson et al., 2019; Whitley et al., 2016). Participants’ responses also support findings from a review on the resources refugee youth may need to integrate successfully into their new culture (Rivera et al., 2016). Refugees who felt competent in many areas of their life were more likely to exhibit high levels of resilience. While the cognitive and behavioral consequences of this perceived incompetence in PA activities were beyond the scope of this study, the pervasiveness of the perceived incompetence in the interviews cannot be ignored. SDT is clear that competence is, at its core, a basic human psychological need (Ryan & Deci, 2000), so sport and school coaches should foster it as such.

Despite reporting little knowledge of common U.S. sports, most participants exhibited positive attitudes toward PA, particularly during PE classes. When asked about their perceptions of PE class, for instance, most of the girls stated they enjoyed it. Barr-Anderson and colleagues (2008) found that about half of their 1500 female youth participants also enjoyed PE, partially depending on its perceived benefits and the girls’ self-efficacy. If the girls in the present study feel competent in PE activities, then they might believe they can effectively take part in the class. One in particular learned how to play tennis after moving to the United States: “When you learn with the team and you work hard, it’s become like a family to you and you really love it” (010-Initial). Here, the resulting competence from learning to play a new sport alongside her teammates helped her feel included and generated positive feelings. When this results in a fun, enjoyable PA experience, youth are more likely to continue doing it (Beni et al., 2017; Hertting & Karlefors, 2013; Robinson et al., 2019).

Figure 2 – Photograph of a soccer ball, representing feelings of incompetence in sport

“I want to do soccer but like, I’m not confident enough, and then like, I’m trying to practice more to get better so I can like, try out probably next year.” (Participant 001)

Growth mindset. Participants’ feelings of incompetence in PE activities seemed to be countered at times with a growth mindset, defined as a positive approach to a task where individuals believe practice will improve how they perform that task (Mrazek et al., 2018). This mindset includes seeing obstacles as challenges rather than threats, repeatedly trying tasks despite failure, and being motivated by others’ success (Dweck, 2006). Many of the participants shared their intent to improve their skills and learn new sports because it was enjoyable. When asked what she would try if she could do any PA she wanted, one said, “I want to do soccer but like, I’m not confident enough, and then like, I’m trying to practice more to get better so I can like try out probably next year” (001-Follow-up).

Though fear of not making the soccer team impacted her decision to try out, she admitted she still wanted to work on her skills to feel prepared for future tryouts. This notion is supported by a study in which learning new skills was the most commonly cited reason that refugees in Australia participated in PA and sports (Olliff, 2008). Olliff (2008) also found sport and recreation to be a platform for capacity building, problem solving, and working on personal development, all of which overlap with a growth mindset. By approaching tasks with a growth mindset, perhaps this participant finds herself more intrinsically motivated to do PA. Though some girls demonstrate the growth mindset by confronting challenges wholeheartedly, others admitted avoiding activities or sports in which they feel incompetent. It would be important, therefore, for SDP programs and PE classes to provide an environment conducive to refugee students being appropriately challenged, providing enough information about the rules and skillsets for novel activities, and adapting to youths’ needs (Anderson et al., 2019; Barr-Anderson et al., 2008; Whitley et al., 2016).

Lack of indoor PA options and accessibility. Similar to feeling they have insufficient knowledge of sports rules and skills in PE class, participants shared barriers to PA relating to wintertime, namely, poor weather conditions. This barrier is consistent with findings on the link between changing seasons and PA behaviors in youth, with warmer weather correlating to more time engaged in PA compared to colder weather (Harrison et al., 2017). To further illustrate this, one individual stated, “If the weather’s good, I tend to go out more, but if like, the weather’s like bad, like I tend to stay inside I guess” (007-Follow-up). Most participants shared this sentiment and did not know how to conduct indoor PA, one participant even preferring lying in bed to doing anything else. While PE class gives them an opportunity to use special equipment such as a treadmill, hand weights, and a stationary bike, participants do not have access to such resources at home and very limited access to transportation to visit a gym, according to several girls. One potential reason for this resistance to find PA alternatives could be a lack of what Yam (2017) called “health literacy,” or general knowledge about caring for one’s health. Results from O’Driscoll and colleagues’ (2014) review suggest it is possible that more knowledge about indoor activities would encourage PA. Thus, without knowing the benefits and ways to engage in PA, they are less likely to participate. Moreover, poor and/or inaccessible PA infrastructure is common in communities with families from refugee backgrounds (Jeanes et al., 2015; Langøin et al., 2017), and SDP researchers have identified proper facilities as an essential component of effective programming (Clutterbuck & Doherty, 2019; Svennson & Woods, 2017). If communities do have winter sports programs, however, increased awareness might encourage PA. It may be difficult to disseminate this information to families from refugee backgrounds, as they may feel discomfort toward novel PA (Wieland et al., 2015). It may fall on school administrators and community outreach programs to include this group and make PA more accessible (Dagkas et al., 2011; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Robinson et al., 2019; Spaaij, 2015).

Some participants, however, took an extra step to do PA in winter. An individual who took a photograph of her phone said she uses it for, “like stretching, like how to do some stretches. You watch YouTube” (012-Follow-up). Another individual photographed a space in her room where she does squats and core exercises daily: “I just wake up, take shower in the morning and this is like, something that I do every single day in the morning, in the evening” (010-Follow-up). These represent exceptions to this subdimension. Most of the girls were unsure of how to conduct themselves in the wintertime and resorted to sedentary activities that were simple and familiar. This finding agrees with research indicating lack of access to information about PA, which could lead to discomfort with becoming physically active, were significant PA barriers for refugee families (O’Driscoll et al., 2014; Wieland et al., 2015).

Autonomy

Ryan and Deci’s (2000) second component of SDT is autonomy, or the feeling of having control of one’s life. They indicate that individuals learn better, and can thus increase competence, if they feel autonomous throughout the learning process. Two important subdimensions emerged from the current data: (a) importance of choice and autonomy, and (b) the balance of individual and group PA opportunities.

Importance of choice and autonomy. All but one participant said that she is more likely to do PA if she chooses it and less likely if someone else chooses. This accords with White et al’s (2018) study results that linked forced PA to negative affect. Because most refugees involuntarily flee their homeland and are placed in a new country, they have no control over their situation (Edge et al., 2014). Participation in PA, however, seemed to mitigate this feeling of lack of control. One individual stated,

I feel great when I make the decision that I wanna do something. Like, it help you a lot, just like, you only do something that you wanna do. But not somebody chose for you. That’s a good thing to do. (005-Initial)

Having the power to make decisions brings about positive emotions for this individual, which is consistent with how SDT works to incite motivation. Research has shown that fostering independence can buffer against negative psychological outcomes (Bean et al., 2014; Edge et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2016; Pieloch et al., 2016), thus reinforcing the importance of encouraging youth from refugee backgrounds to make their own choices. Research also supports the notion of choice in sport, where coaches or teachers can aid positive youth development by including athletes when making decisions (Bean et al., 2014; Beni et al., 2017; Elbe et al., 2018). Consequently, youth from refugee backgrounds may benefit in and out of sport from making decisions about their sport participation (Elbe et al., 2018).

Figure 3 – Photograph of roller skates representing importance of choice and autonomy

“It’s like a calming activity. ’Cause like roller skating you don’t need like, other people to be with you to like do it. . . . But I go with her [dog] sometimes.” (Participant 007)

Balance of individual and group PA. It was clear that participants generally valued both group and individual PA opportunities. When asked which type she preferred, one participant said, “I think I like [PA] with somebody because it’s like, more fun, more enjoyable to do it. And being alone, like being alone’s a little bit better I guess ’cause you can like, think to yourself,” (001-Initial). It is apparent that there are benefits to doing PA with a friend or family member, such as feeling joy through camaraderie (Beni et al., 2017; Olliff, 2008), in addition to benefits to doing PA by herself, such as personal reflection time. Another participant echoed this notion when describing a photograph of her roller skates: “It’s like a calming activity. ’Cause like roller skating, you don’t need other people to be with you to do it” (007-Follow-up).

She later described how she enjoys practicing basketball with her siblings, which is a fun challenge. This preference for balance is logical but not fully supported by research. Many studies promote group bouts of PA, as it can be effective in creating social capital for refugees who may already be at a social disadvantage (Anderson et al., 2019; Block & Gibbs, 2017; Nathan et al., 2010; Olliff, 2008; Whitley et al., 2016). It is possible that the participants in this study are old enough to see and appreciate the benefits of doing PA alone and as a group.

Relatedness

The final component of SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000) is relatedness. Relationships are certainly important to this group, and research indicates that social connections are absolutely crucial for wellness (Hadfield et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2016; Olliff, 2008; Rivera et al., 2016). The most commonly cited factor that impacted participants’ PA participation was peer, adult, and family relationships. Two additional subdimensions were monoethnic relationships and a lack of community involvement and support.

Peer, adult, and family relationships. Results from many studies have indicated that the formation of peer relationships can help refugees experience healthy resettlement, whether this occurs in school (Hadfield et al., 2017; Şeker & Sirkeci, 2015; Shakya et al., 2010), the community (Ellis et al., 2016; Spaaij, 2015), and/or sport (Block & Gibbs, 2017; Dukic et al., 2017; Ha & Lyras, 2013; McDonald et al., 2019; Mohammadi, 2019; Olliff, 2008). Unsurprisingly, every participant in the present study commented on how important relationships were to her. This emerged in the realm of her family, peers, and important adults in her life such as teachers or an interpreter. When asked what the best part of participating in PA was, one said,

The best part is that if you do it with friend, then you’re doing it with a friend, and you’re having fun, and that’s like the best part. Like hanging out with a friend is just an excuse to hang out with a friend, but you’re also doing something. (012-Initial)

For this individual, her friends not only make PA fun, but they motivate and include her. This is consistent with Olliff’s (2008) findings where making new friends was a commonly cited reason for refugees participating in sport and recreation. Many participants also noted being with their friends made them feel as if they belonged or “fit in.” Considering the uncertainty, fear, and anxiety that migration can bring, connecting with peers may ease those challenges by offering an opportunity for inclusion (Lleixá & Nieva, 2018; McDonald et al., 2019; Mohammadi, 2019).

Relationships for the participants extend beyond peers to their families. In fact, the girls’ families were discussed so often they seemed to be prioritized over peer relationships. Participants with siblings close in age spent many afternoons each week playing outside and practicing sports skills together. Those with much older siblings typically cared for their nieces and nephews after school. In one case, babysitting interfered with a participant’s ability to play a school sport: “I was trying out to make it to a [soccer] team, but then I quit, ’cause I gotta babysit right after school” (005-Initial). Family and their related obligations appear to be the girls’ first priority, which supports research indicating that sociocultural factors, in this case, familial roles and responsibilities, notably influenced ethnic minorities’ PA levels (Caperchione et al., 2011; Kay & Spaaij, 2012; Langøien et al., 2017). The closeness within each girl’s family appeared to both facilitate and prevent PA, supporting findings by Kay and Spaaij (2012). For instance, one participant reported her family being a major support system for their PA endeavors:

They [family members] tell me to do soccer, like my uncle too, like, “You should play soccer, you seem to be good at it.” Then, “You should play in the USA team,” something like that. I’m like how am I supposed to play that, I’m not that skilled. He like, “You gotta practice then, I can help you.” (004-Initial)

This familial support for PA can help motivate refugee girls to engage in healthy extracurricular activities, but family obligations can get in the way of sport participation (Kay & Spaaij, 2012). In a review by Rivera and colleagues (2016), family was portrayed as a potential protective factor to refugees’ migration, as well as a fragile unit that the stresses of migration could break apart. Proper sport orientations for athletes and their families would ensure understanding and solidify expectations (Bean et al., 2014; Dagkas et al., 2011), and discuss ways to mitigate the financial strains and distress sports can elicit (Bean et al., 2014). While harrowing migration experiences might bring families together, family time may be detrimental to youth’s psychological well-being if it is mutually exclusive from PA participation.

Monoethnic relationships. Because refugees are typically relocated en masse, ethnic groups might live in concentrated areas, encouraging monoethnic relationships (Weng & Lee, 2015). In other words, refugee communities interact with those most similar to them, to preserve culture and traditions and maintain comfort in a new place (Weng & Lee, 2015). For those in this study, monoethnic relationships were the most common type of peer relationship. Two participants met when they moved to the United States 10 years ago and have been friends since: “We’ve known each other for a long time. And we enjoy um, the same sport. . . . She’s supportive, um caring, and honest” (001-Initial). After several other interviews, the girls were mentioning one another’s names when asked about certain experiences, suggesting the individuals had fewer nonrefugee friends and mostly spent time with one another and their families. In the sport domain, a case can be made for monoethnic sports teams because they allow people to share a culture and language, feel a sense of belonging, and feel accepted (Fader et al., 2019; Spaaij, 2015). This may engage youth with refugee backgrounds in a safe environment with familiar people. Jeanes et al. (2015) found refugee youth in Australia preferred playing informally to structured sport club teams, which could apply to this population considering their various responsibilities.

Lack of community support. The relationships refugees build on the interpersonal and community levels can be crucial for their sense of belonging and successful resettlement. Several participants in their interviews said they had little to no contact with their neighbors or community. When asked how her community perceives PA participation, one responded, “We just stay in our house. We don’t bother other people” (009-Initial). Another’s response was, “We’re not that friendly. I mean, we’re friendly but we just don’t know that much people [in the community]” (002-Initial). Two girls did express that their community was supportive of their sport and PA participation, but the majority were at a loss when asked to describe how they interact with people who live near them. To clarify, it did not seem like the girls’ communities were purposefully unsupportive or hostile toward them; rather, it seemed there was an absence of interaction and support. It has been argued that communities need to do more to reach out and include families and youth with refugee backgrounds (Dagkas et al., 2011; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Robinson et al., 2019; Spaaij, 2015). SDP practitioners echo this by wanting to engage with community stakeholders as well (Whitley et al., 2019). Weng and Lee (2015) suggest first recognizing this population’s capacity to contribute, because they want to be involved. Then, communities could create grassroots programs and partner with schools to increase involvement (Brenner & Kia-Keating, 2016; Robinson et al., 2019).

Two participants mentioned getting more involved with their communities. They wanted to meet more people and become more integrated with those living near them. This can occur through sport, as playing with community members can connect people of similar backgrounds and build intercultural understanding (Fader et al., 2019; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Stodolska & Alexandris, 2004) and can be a gateway to additional participation, such as volunteering (Stone, 2018). Thus, not knowing about or having community support may impact participants’ ability to resettle.

Practical Implications

Results from the interviews reveal several implications for practitioners, school-related personnel, and the field of SDP. The data imply that female youth from refugee backgrounds may benefit from opportunities to be autonomous, learn common U.S. sports in a nonjudgmental environment, and connect with nonrefugee classmates. To facilitate choice and autonomy, PE teachers and coaches could provide youth with leadership opportunities, work with community programs, and teach decision-making skills (Elbe et al., 2018; Pieloch et al., 2016). For instance, coaches could have athletes choose a skill to focus on first, like shooting, passing, or dribbling. For a population with little control over their situation, an autonomy-supportive environment can increase motivation and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

To combat feelings of incompetence in sport and lack of indoor PA options and accessibility, PE teachers and coaches could collaborate and establish at-home routines for students during winter, which could enhance knowledge and competence. Refugee families have expressed a major barrier to PA was not knowing how to start (Wieland et al., 2015). Thus, refugees’ general lack of experience and knowledge of PA (Langøien et al., 2017) warrant increased accessibility and education on the potential benefits of PA. This could be done through SDP programs, which often combine education and sport to teach life skills, but practitioners must be cautious of both positive and negative outcomes (Svennson & Woods, 2017).

Coaches, PE teachers, school administrators, and SDP practitioners have the power to elicit positive PA experiences for female youth from refugee backgrounds. Careful planning and heightened awareness of this population’s needs can fulfill these girls’ psychological needs. Helping these students connect with nonrefugee classmates through mixed-group sports drills, PE teams, and learning U.S. sports rules can enhance social capital and a sense of belonging (Anderson et al., 2019; Block & Gibbs, 2017; Nathan et al., 2010; Olliff, 2008; Whitley et al., 2016). SDP practitioners, sport coaches, and teachers can use these findings to ensure programs are sensitive to the group’s culture, finances, social preferences, and physical abilities. The result is an understanding of the experiences of their refugee students (Spaaij, 2013) and an ability to foster autonomy, relationships, and belonging.

Limitations and Future Directions

While there were some valuable findings, several methodological limitations may have impacted the results of this study. First, participants were sufficiently settled in their communities and spoke fluent English. Selection bias existed in choosing to work with this group because their refugee experiences were far removed (M = 8 years), and their seeming integration into the U.S. lifestyle could impact the extent of their PA experiences. In addition, there was a lack of meaningfulness in participants’ photos, which authors attribute to potentially ambiguous photovoice instructions, participants not doing enough daily PA to photograph, and lack of time. Future researchers should ask about the barriers to taking photos to gain insight about this limitation. Additionally, providing digital cameras, which are arguably obsolete, for photovoice may have made it uncomfortable to take photos in public places. Completing the task may have been easier if participants use their personal camera devices (e.g., smart phones).

In the future, researchers might focus on female youth refugees’ resettlement as it relates to only sport, exercise, or PE class, rather than all three. This might increase clarity about how sport, exercise or PE class truly impacts resettlement. In addition, it would be beneficial to investigate refugees’ use of indoor and outdoor space, as they may be used differently compared to youth born in the United States. Having participants write down key words about each photo immediately after taking it may add depth to the follow-up interview, as opposed to a purely retrospective discussion. Finally, it is worth exploring the self-identification of the term “refugee.” By understanding how those who society calls “refugees” actually identify with that term, and for how long after they migrate they continue to identify with it, coaches and teachers can treat and address them in a culturally sensitive manner.

CONCLUSION

This manuscript reports the findings from one research question related to a larger study investigating the role that PA, exercise, and sport play in female youth refugees’ autonomy, belonging, and relationships. Themes resulting from semistructured interviews were deductively analyzed using SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The following subdimensions emerged: feelings of incompetence in sport; growth mindset; lack of indoor PA options and accessibility; importance of choice and autonomy; balance of individual and group PA; peer, adult, and family relationships; monoethnic relationships; and lack of community support. The results from this study support SDT and photovoice as viable ways of understanding this population’s PA and sport experiences. However, future researchers planning to use SDT may consider an additional theory such as Sport for Development Theory (Lyras & Peachey, 2011), Critical Feminist Theory (Erden, 2017) or a socioecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) to more comprehensively conceptualize female youth’s experiences. Nonetheless, these results support sport and PA as a way for female youth with refugee backgrounds to feel autonomous and competent as they practice PA-related skills and connect with others. This work attempts to add to the scant literature on this unique population’s PA experiences and to the growing body of research on SDP with refugees (Collison et al., 2017; Clutterbuck & Doherty, 2019; Ha & Lyras, 2013; Whitley et al., 2016). It provides further insights to this group’s preferences and needs in PA, so SDP practitioners may consider them for programming. Though generally content with their PA experiences, feelings of incompetence in PE class warrant additional support from PE teachers and peers. Community support could help expand this group’s social networks in and out of PA. School administrators and coaches should work to understand this population’s familiarity with PA and how a lack of experience may explain their level of engagement. By learning what prevents and encourages their participation, PE classes and sports practices can be modified to reflect the needs of this group (Anderson et al., 2019; Whitley et al., 2016). For a population that will always be present and dynamic in the United States, it is necessary for teachers and coaches to initiate conversations with their youth from refugee backgrounds about how they might prefer to engage in PA and sport.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

Funding for this study was provided by the Hollis Fund through Ball State University’s Aspire Internal Grants Program. The funding source had no involvement in the in the study design, analysis, writing, or decision to publish.

REFERENCES

Anderson, A., Dixon, M. A., Oshiro, K. F., Wicker, P., Cunningham, G. B., & Heere, B. (2019). Managerial perceptions of factors affecting the design and delivery of sport for health programs for refugee populations. Sport Management Review, 22(1), 80-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.015

Aspen Institute Project Play. (2018). State of play 2018: Trends and developments. https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2018/10/StateofPlay2018_v4WEB_2-FINAL.pdf

Barr-Anderson, D. J., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Schmitz, K. H., Ward, D. S., Conway, T. L., Pratt, C., Baggett, C. D., Lytle, L., & Pate, R. R. (2008). But I like PE: Factors associated with enjoyment of physical education class in middle school girls. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 79(1), 18-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2008.10599456

Barron, S., Okell, J., Yin, S. M., VanBik, K. Swain, A., Larkin, E., Allott, A. J., & Ewers, K. (2007). Refugees from Burma: Their backgrounds and refugee experiences. Cultural Orientation Resource Center. http://www.culturalorientation.net/content/download/1338/7825/version/2/file/refugeesfromburma.pdf

Bean, C., Fortier, M., Post, C., & Chima, K. (2014). Understanding how organized youth sport may be harming individual players within the family unit: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(10), 10226-10268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111010226

Bean, C., Harlow, M., Mosher, A., Fraser-Thomas, J., & Forneris, T. (2018). Assessing differences in athlete-reported outcomes between high- and low-quality youth sport programs. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(4), 456-472. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1413019

Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

Block, K., & Gibbs, L. (2017). Promoting social inclusion through sport for refugee-background youth in Australia: Analysing different participation models. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 91-100. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.903

Block, K., Warr, D., Gibbs, L., & Riggs, E. (2013). Addressing ethical and methodological challenges in research with refugee-background young people: Reflections from the field. Journal of Refugee Studies, 26(1), 69-87. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fes002

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brenner, M. E., & Kia-Keating, M. (2016). Psychosocial and academic adjustment among resettled refugee youth. In A. Wiseman (Ed.) Annual Review of Comparative and International Education 2016 (pp. 221-249). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and esign. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Caperchione, C. M., Kolt, G. S., Tennent, R., & Mummery, W. K. (2011). Physical activity behaviours of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) women living in Australia: A qualitative study of socio-cultural influences. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 26-26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-26

Clutterbuck, R., & Doherty, A. (2019). Organizational capacity for domestic sport for development. Journal of Sport for Development, 7(12), 16–32.

Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as “Positive development?” Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 35(3), 306-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723511417311

Coalter, F. (2015). Sport-for-change: Some thoughts from a sceptic. Social Inclusion, 3(3), 19- 23. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i3.222

Collison, H., Darnell, S., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (2017). The inclusion conundrum: A critical account of youth and gender issues within and beyond sport for development and peace interventions. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.888

Couch, J. (2007). Mind the gap: Considering the participation of refugee young people. Youth Studies Australia, 26(4), 37-44.

Dagkas, S., Benn, T., & Jawad, H. (2011). Multiple voices: Improving participation of Muslim girls in physical education and school sport. Sport, Education and Society, 16(2), 223-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.540427

Dávila, L. T. (2014). Representing refugee youth in qualitative research: Questions of ethics, language and authenticity. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 8(1), 21-31.

Dukic, D. McDonald, B., & Spaaij, R. (2017). Being able to play: Experiences of social inclusion and exclusion within a football team of people seeking asylum. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 101-110. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.892

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success (1st ed.). New York: Random House.

Dwyer, E., & McCloskey, M. L. (2013). Literacy, teens, refugees, and soccer. Refuge, 29(1), 87- 101.

Edge, S., Newbold, K., & McKeary, M. (2014). Exploring socio-cultural factors that mediate, facilitate, & constrain the health and empowerment of refugee youth. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 34-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.025

Elbe, A., Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Morela, E., Ries, F., Kouli, O., & Sanchez, X. (2018). Acculturation through sport: Different contexts different meanings. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(2), 178-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1187654

Ellis, B., Abdi, S., Lazarevic, V., White, M., Lincoln, A., Stern, J., & Horgan, J. (2016). Relation of psychosocial factors to diverse behaviors and attitudes among Somali refugees. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(4), 393-408. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000121

Erden, O. (2017). Building bridges for refugee empowerment. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 18(1), 249-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-016-0476-y

Fader, N., Legg, E., & Ross, A. (2019). The relation of sense of community in sport on resilience and cultural adjustment for youth refugees. World Leisure Journal, 61(4), 291-302.

Gibbens, S. (2017, September 29). Myanmar’s Rohingya are in crisis: What you need to know. National Geographic. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/09/rohigya-refugee-crisis-myanmar-burma-spd/

Griciūtė, A. (2016). Optimal level of participation in sport activities according to gender and age can be associated with higher resilience: Study of Lithuanian adolescents. School Mental Health, 8, 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9155-y

Ha, J. P., & Lyras, A. (2013). Sport for refugee youth in a new society: The role of acculturation in sport for development and peace programming. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 2013, 35(2), 121-140.

Hadfield, K., Ostrowski, A., & Ungar, M. (2017). What can we expect of the mental health and well-being of Syrian refugee children and adolescents in Canada? Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 58(2), 194-201. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000102

Harrison, F., Goodman, A., van Sluijs, E., Andersen, L., Cardon, G., Davey, R., Janz, K. F., Kriemler, S., Molloy, L., Page, A. S., Pate, R., Puder, J. J., Sardinha, L. B., Timperio, A., Wedderkopp, N., & Jones, A. P. (2017). Weather and children’s physical activity; how and why do relationships vary between countries? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0526-7

Hertting, K., & Karlefors, I. (2013). Sport as a context for integration: Newly arrived immigrant children in Sweden drawing sporting experiences. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(18), 35.

Jacob, S. A., & Furgerson, S. P. (2012). Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: Tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 17(6), 1-10.

Jani, J., Underwood, D., & Ranweiler, J. (2016). Hope as a crucial factor in integration among unaccompanied immigrant youth in the USA: A pilot project. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(4), 1195-1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0457-6

Jeanes, R., O’Connor, J., & Alfrey, L. (2015). Sport and the resettlement of young people from refugee backgrounds in Australia. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 39(6), 480-500.

Kay, T., & Spaaij, R. (2012). The mediating effects of family on sport in international development contexts. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 47(1), 77-94.

Keddie, A. (2011). Supporting minority students through a reflexive approach to empowerment. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(2), 221-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.547307

Langøien, L. J., Terragni, L., Rugseth, G., Nicolaou, M., Holdsworth, M., Stronks, K., Lien, A., & Roos, G. (2017). Systematic mapping review of the factors influencing physical activity and sedentary behaviour in ethnic minority groups in Europe: A DEDIPAC study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(99), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0554-3

Lleixà, T., & Nieva, C. (2018). The social inclusion of immigrant girls in and through physical education: Perceptions and decisions of physical education teachers. Sport, Education and Society, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1563882

Lyras, A., & Peachey, J. W. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Management Review, 14, 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.05.006

MacDonnell, M., & Schmidt, S. (2012). Refugee families from Burma. Head Start/ECLKC. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/cb-refugee-families-burma-eng.pdf

Marshall, E., Butler, K., Roche, T., Cumming, J., & Taknint, J. (2016). Refugee youth: A review of mental health counselling issues and practices. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 57(2A), 308-319. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000068

McDonald, B., Spaaij, R., & Dukic, D. (2019). Moments of social inclusion: Asylum seekers, football and solidarity. Sport in Society, 22(6), 935-949.

McKay, C. D., Cumming, S. P., & Blake, T. (2019). Youth sport: Friend or foe? Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 33(1), 141-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.017

McLaughlin, C., & Black-Hawkins, K. (2004). A schools-university research partnership: Understandings, models and complexities. Journal of in-Service Education, 30(2), 265-284. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580400200319

Merkel, D. L. (2013). Youth sport: Positive and negative impact on young athletes. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, (4), 151-160.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th edition.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mohammadi, S. (2019). Social inclusion of newly arrived female asylum seekers and refugees through a community sport initiative: The case of Bike Bridge. Sport in Society, 22(6), 1082-1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1565391

Mrazek, M. D., Mrazek, A. J., Ihm, E. D., Molden, D. C., Zedelius, C. M., & Schooler, J. W. (2018). Expanding minds: Growth mindsets of self-regulation and the influences on effort and perseverance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 164-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.07.003

Nathan, S., Bunde-Birouste, A., Evers, C., Kemp, L., MacKenzie, J., & Henley, R. (2010). Social cohesion through football: A quasi-experimental mixed methods design to evaluate a complex health promotion program. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 587-587. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-587

O’Driscoll, T., Banting, L. K., Borkoles, E., Eime, R., & Polman, R. (2014). A systematic literature review of sport and physical activity participation in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) migrant populations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(3), 515-530.

Olliff, L. (2008). Playing for the future: The role of sport and recreation in supporting refugee young people to “settle well” in Australia. Youth Studies Australia, 27(1), 52-60.

Palmer, C. (2009). Soccer and the politics of identity for young Muslim refugee women in south Australia. Soccer & Society, 10(1), 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970802472643

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2012). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 18(2), 361-369.

Pieloch, K., McCullough, M., & Marks, A. (2016). Resilience of children with refugee statuses: A research review. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 57(2A), 330-339. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000073

Prior, M. A., & Niesz, T. (2013). Refugee children’s adaptation to American early childhood classrooms: A narrative inquiry. The Qualitative Report, 18(20), 1-17.

Rivera, H., Lynch, J., Li, J., & Obamehinti, F. (2016). Infusing sociocultural perspectives into capacity building activities to meet the needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 57(2A), 320-329. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000076

Robinson, D. B., Robinson, I. M., Currie, V., & Hall, N. (2019). The Syrian Canadian sports club: A community-based participatory action research project with/for Syrian youth refugees. Social Sciences, 8(6), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060163

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryu, M., & Tuvilla, M. R. S. (2018). Resettled refugee youths’ stories of migration, schooling, and future: Challenging dominant narratives about refugees. The Urban Review, 50(4), 539-558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0455-z

Şeker, B. D., & Sirkeci, I. (2015). Challenges for refugee children at school in eastern Turkey. Economics & Sociology, 8(4), 122-133. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-4/9

Shakya, Y. B., Guruge, S., Hynie, M., Akbari, A., Malik, M., Htoo, S., Khogali, A., Mona, S. A., Murtaza, R., & Alley, S. (2010). Aspirations for higher education among newcomer refugee youth in Toronto: Expectations, challenges, and strategies. Refuge: Canada’s Periodical on Refugees, 27(2), 65-78.

Spaaij, R. (2013). Cultural diversity in community sport: An ethnographic inquiry of Somali Australians’ experiences. Sport Management Review, 16(1), 29-40.

Spaaij, R. (2015) Refugee youth, belonging and community sport. Leisure Studies, 34(3), 303-318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.893006

Stodolska, M. & Alexandris, K. (2004). The role of recreational sport in the adaptation of first generation immigrants in the United States. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(3): 379-413.

Stone, C. (2018). Utopian community football? Sport, hope and belongingness in the lives of refugees and asylum seekers. Leisure Studies, 37(2), 171-183.

Strack, R. W., Magill, C., & McDonagh, K. (2004). Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 5(1), 49.

Stura, C. (2019). “What makes us strong”: The role of sports clubs in facilitating integration of refugees. European Journal for Sport and Society, 16(2), 128-145.

Svensson, P. G., Woods, H. (2017). A systematic overview of sport for development and peace organisations. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(9): 36-48.

Thomas, J. R., Nelson, J. K., & Silverman, S. J. (2010). Research methods in physical activity. (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Tribe, R. (2005). The mental health needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Mental Health Review Journal, 10(4), 8-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/13619322200500033

Ubaidulloev, Z. (2018). Sport for peace: A new era of international cooperation and peace through sport. Asia-Pacific Review, 25(2), 104-126.

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. (2019). Figures at a glance: Statistical yearbooks. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html?query=figures%20at%20a%20glance

U.N. Refugee Agency. (2019). Sport Programmes and Partnerships: International Olympic Committee. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/sport-partnerships.html

van Liempt, I. V., & Bilger, V. (2012). Ethical challenges in research with vulnerable migrants. In C. Vargas-Silva (Ed.) Handbook of Research Methods in Migration (pp. 451-466). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Wang, C., & Burris, A. M. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 24(3), 369-387.

Weng, S. S., & Lee, J. S. (2015). Why do immigrants and refugees give back to their communities and what can we learn from their civic engagement? Voluntas, 27, 509-524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9636-5

White, R. L., & Bennie, A. (2015). Resilience in youth sport: A qualitative investigation of gymnastics coach and athlete perceptions. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(2-3), 379-393. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.10.2-3.379

White, R., Parker, P., Lubans, D., MacMillan, F., Olson, R., Astell-Burt, T., & Lonsdale, C. (2018). Domain-specific physical activity and affective wellbeing among adolescents: An observational study of the moderating roles of autonomous and controlled motivation. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1), 87-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0722-0

Whitley, M. A., Coble, C., & Jewell, G. S. (2016). Evaluation of a sport-based youth development programme for refugees. Leisure, 40(2), 175-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2016.1219966

Whitley, M. A., Farrell, K., Wolff, E. A., & Hillyer, S. J. (2019) Sport for development and peace: Surveying actors in the field. Journal of Sport for Development, 7(11),1-15.

Whitley, M. A., & Gould, D. (2011). Psychosocial development in refugee children and youth through the personal-social responsibility model. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 1(3), 118-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2010.534546

Wieland, M. L., Tiedje, K., Meiers, S. J., Mohamed, A. A., Formea, C. M., Ridgeway, J. L., Asiedu, G. B., Boyum, G., Weis, J. A., Nigon, J. A., Patten, C. A., & Sia, I. G. (2015). Perspectives on physical activity among immigrants and refugees to a small urban community in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(1), 263-275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9917-2

Yam, A. E. (2017). Using photovoice as participatory action research to identify views and perceptions on health and well-being among a group of Burmese refugees resettled in Houston (Publication No. 10284921) [Doctoral dissertation, Texas Women’s University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.