Lindsey C. Blom1, Lawrence Gerstein2, Kelley Stedman3, Lawrence Judge4, Alisha Sink4, David Pierce5

1 Ball State University, School of PE, Sport, & Exercise Science, The Center for Peace and Conflict Studies, USA

2 Ball State University, Department of Counseling Psychology, The Center for Peace and Conflict Studies, USA

3 Ball State University, Social Science Research Center, USA

4 Ball State University, School of PE, Sport, & Exercise Science, USA

5 Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, Department of Kinesiology, USA

Citation: Blom, LC, Gerstein, L, Stedman, K, Judge, L, Sink, A, Pierce, D. Soccer for Peace: Evaluation of In-Country Workshops with Jordanian Coaches. Journal of Sport for Development. 2015; 3(4): 1-12.

Abstract

The Soccer for Peace Programme used a sport plus approach to teach Jordanian coaches how to develop and instill citizenship, peaceful living, and leadership skills in youth through football. Through the program, which is based on sport-for-development theory (SFDT) and a train the trainer approach, coaches learned how to create a positive environment for their teams. Specifically, the programme was designed to improve coaches’ skills in developing citizenship behaviours and peaceful living skills in their athletes; advance coaches’ knowledge about technical and tactical aspects of coaching football; and to promote mutual understanding. Upon completing the programme, coaches (n = 115) reported being more knowledgeable about football and peaceful living skills, satisfied with their experience, as well as prepared and confident to teach their new knowledge to athletes. Coaches’ participation also affected their comfort when working with someone of another gender, but not another culture (mutual understanding). Limitations, implications, and future research ideas are also discussed.

Background

When the concept of peace is discussed, the focus is often centered on the absence of violence; violence otherwise termed as negative peace.1 Positive peace, on the other hand, involves actively challenging environments and societal norms that foster inequities to prevent further cycles of violence and conflict. 2,3 Positive peace is particularly relevant in the development of peace-building strategies, which typically involve a grassroots, positive approach. These strategies create a structure of peace by addressing the underlying causes of conflict within social, psychological and economic environments, and are often focused person-to-person.1,4 Sport is a growing positive peace strategy.

Lyras’5,8 sport-for-development theory (SFDT) is a useful framework for developing effective sport-based positive peace programmes that help build peace. The foundation of SFDT is based upon the facilitation of human development and inter-group acceptance, which in turn is rooted in the theories of Allport9 and Maslow’s10 hierarchy of needs. More specifically, Ryan and Deci’s11 work is grounded in Maslow’s theory emphasizing the need for individuals to feel connected to others, competent to meet their potential, and safe and autonomous in their surroundings in order to promote psycho-social growth and developmental potential. Lyras8 recommended using these concepts to design effective sport for development and peace (SDP) programmes.

To understand the varying purposes of SDP programmes, Coalter6 developed three categories. His sport plus category, which is most relevant to the current study, involves the use of sport in conjunction with non-sport-related education. In this use of sport, the focus of the programme is cooperative, inclusive and mastery-based rather than competitive and outcome-based.5,12 Such a focus challenges the status quo, provides an important step needed for peace-building, and mirrors the more typical non-sport based peace-building strategies that focus on inter-group acceptance.3

In the current study, researchers evaluated a sport plus intervention with the goal of using soccer, also known as football, as a medium to teach children concepts such as citizenship, conflict resolution and leadership skills. Designed with the concepts of SFDT, the current programme focused on teaching Jordanian grassroots coaches how to create a positive environment within their football teams. Coaches were targeted as main participants in a train-the-trainer approach, since coaches are instrumental in teaching these skills as they are often highly respected, viewed as experts, and typically have a lot of direct interaction with youth.13 Furthermore, research indicates that when U.S. coaches have been trained on how to foster a positive sport environment, they demonstrate more positive coaching behaviours post-training,13,14 and youth athletes display increased self-esteem15,17 and more enjoyment in their sport experience.14,16

Internationally, Sugden18 found similar results that emphasize the importance of training coaches in SDP programs as evident in the evaluation of the Football 4 Peace programme, which is designed “to use values-based football coaching to build bridges between neighbouring Jewish and Arab towns and villages in Israel” (p. 405). He found that the facilitators or coaches who were knowledgeable and sympathetic were able to conduct important off-pitch activities and those who were more intimately involved were able to express the positive benefits of the programme. Schulenkorf and Sugden19 also indicated the importance of proper role models to get youth to engage as did Pink and Cameron20 who found corresponding results with their Future in Youth (FIY) soccer project. Coaches felt more competent in their coaching abilities and were more motivated to coach local youth upon completion of the training progammme. However, they did express concerns regarding the barriers to the programme’s sustainability that related to support, transportation and parental attitudes.

Cultural Context for Current Programme

In accordance with recommendations and best practices from previously conducted SDP programmes,18,21-23 the current SDP programme was designed to teach coaches how to incorporate teachable moments and deliberate activities into practice that will further develop their athletes as well as inter-group relations. Specifically, coaches were instructed on how to help youth identify positive team expectations and provide them with constant visual reminders, reinforce problem-solving skills, and support the acknowledgement of others’ feelings, which are all peace-building strategies. Additionally, coaches were taught how to promote empathy, actively listen, mutually respect one another, appreciate diversity, find common ground, and ask questions to identify areas of needed growth among their athletes.18,24,25

The programme took place in Jordan, an Arab kingdom located in the Middle East with an area slightly smaller than the state of Indiana.26,27 Jordan is a constitutional monarchy whose governmental members are appointed.27 Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, the Palestinian territories, and Israel all border Jordan with the Palestinian territories and Israel sharing control of the Dead Sea with the Kingdom.26 The majority (98%) of Jordanians consider themselves Arab, and the other two percent consider themselves Circassian or Armenian.27 Arabic is the official language, while English is widely understood among those in the upper and middle classes.

Few things are closer to the Jordanian heart and psyche than the sport of football.29 Prince Ali bin Al Hussein, the head of the Jordanian Football Association (JFA) and the Vice-President of FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association, or in English, International Federation of Association Football) explained that although in general their Ministry of Education does not allocate significant monetary resources to sports, football is the most popular sport and he emphasized building its infrastructure.30 FIFA reports that as of 2013, there are a total of 121,191 football players in Jordan and of those players 4,941 are registered with the football association while 116,250 are unregistered.31 Most people on every street, from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, play football. It has become even more popular because of the vast improvement in the country’s national football team.29 There also are football-related Little Leagues and Youth Clubs that have become very popular; the Jordan Football Association, the governing body of football in the country, supervises and administers some of them.

Using a train-the-trainer approach, this study was designed to assess two sets of in-country workshops provided through the Sport for Peace and Understanding in Jordan (SPUJ) programme. This programme was designed to teach coaches how to develop citizenship behaviors and conflict resolution skills in youth through the game of soccer. The particular goals of the programme were for coaches to increase their mutual understanding of working with individuals from diverse backgrounds, incorporate possible applied conflict resolution skills in their coaching, and teach methods of coaching soccer effectively. Programme effectiveness was evaluated through three main metrics: a) Increases in content knowledge, b) Increases in mutual understanding scores, and c) Increases in perceived abilities of coaches.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited with the help of in-country organizations to ensure a targeted recruitment effort. A total of 115 Jordanian coaches participated in this study. The majority of the coaches were male (n = 75, 68.8%) around 36 years of age (M=35.78, SD=8.74). The female coaches (n = 34, 31.2%) were approximately 27 years of age (M=27.23, SD=7.80), with six participants who did not report their gender. Overall, coaches ranged from 20 to 49 years of age. The coaches were primarily Arab (81.1%, n = 78), from Jordan (80.3%, n = 102), and had an average of seven years coaching experiences (M = 7.33, SD = 7.09). Evaluation data indicated that approximately 22 coaches attended both sets of in-country workshops.

Instruments

Evaluation involved measuring coaches’ knowledge gains, mutual understanding, perceived abilities, and satisfaction through a pre/post-test descriptive design.

Knowledge. A multiple-choice, criterion-referenced pre/post-test of subject material assessed coaches’ knowledge gains. Content experts, who were responsible for training the Jordanian participants in football-specific coaching and peaceful living skills, developed the test measurements. The football items addressed strength and conditioning along with technical and tactical training topics, while the peaceful living items pertained to both the good citizens’ curriculum and the peaceful living curriculum.

Mutual Understanding. Mutual understanding was operationalized as a lack of social avoidance and rejection, which is a dimension of “social distance.” The construct of social distance was measured through an adapted version of the Bogardus’ Social Distance Scale,32 which was determined as the most appropriate device to use based on its reliability and validity.33-37 The evaluation involved a series of Likert statements (see Results section for specific examples) using a 4-point scale (1 “Strongly Disagree” to 4 “Strongly Agree”).

Perceived Abilities and Satisfaction. Instrumentation also included coaches’ self-reported assessment of their perceived levels of the efficiency, effectiveness and satisfaction with the overall programme using a 4-point Likert-type scale, (1 “Strongly Disagree” to 4 “Strongly Agree”). Self-reported “preparedness” implied how efficient instructors were at delivering quality information to the participants where participants perceived a real increase in their personal skill sets. Self-reported “confidence” illustrated the participants’ perceived ability to return to their individual context and incorporate the skills learned and served as a reflection of the effectiveness of instruction.

Programme

The programme was designed for coaches to learn how to develop citizenship behaviours and peaceful living skills in their athletes through the game of football. In a “train-the-trainer” approach, the coaching clinics were constructed to integrate information on technical football skills with techniques on building citizenship and peaceful living skills. The curriculum was based on curricula developed by the Indiana Soccer Association, the Peace Learning Center (PLC) of Indianapolis, and Ball State University’s Center for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS). The curriculum also included topics suggested in the SFDT:8

- Citizenship Development: The Indiana Soccer Association Human Development (HD) Project: The Indiana Soccer Association developed this curriculum with the purpose of introducing techniques and drills that coaches could use to develop good citizenship alongside strong and healthy habits in their players through the game of football. “HD” stands for human development and high definition meaning that football organizations can offer more than just a picture of good football.

- Leadership: Based on the social learning theory38 and flow theory,39 the curriculum included coaching techniques that can be used to foster cooperation, autonomous behaviours, feelings of competence, enjoyment, and motivation among individual athletes. Furthermore, discussions included positive coaching practices and methods for establishing a mastery-oriented environment.

- Peaceful Living Skills Curriculum: This component of the programme was based on the definition of Christie, Wagner, and Winter40 that peace is the nonviolent resolution of conflict and the pursuit of social justice, which are considered to be peacemaking and peace building, respectively. In order to serve as positive role models, which is an important component of SFDT, coaches learned skills that relate to the ability to live peacefully with others such as assuming personal responsibility, understanding conflict, communicating effectively, respecting cross-cultural differences and similarities, and using the STEP method (a synthesis of conflict resolution and mediation techniques) to effectively resolve conflict.9 Coaches subsequently learned how to promote these skills within their athletes.

It is important to note that many Jordanian education institutions, especially primary and secondary schools, stress rote memorization as a primary mode of instruction. However, the project team’s experiences with Jordanian students suggested that children and adults were both capable of and excited about active learning techniques such as role-playing as well as large or small group discussions. Consequently, the study employed a problem-based educational approach using physical activities as a way to encourage the full engagement of coaches and players during the clinics. At the end of the coaches’ clinics, the newly trained coaches in conjunction with the project staff led clinics for local youth football athletes using the material from the earlier training sessions.

Analysis

All instrumentation used and the methodology described was approved by the researchers’ Institutional Review Board (IRB) prior to its administration. Instruments were translated into Arabic and administered to participants either in classrooms or on the football field during the exchange visits. Participants were instructed to use a combination of their initials and birthdate to accurately pair pre/post-tests. Upon return, all data were entered and analyzed using SPSS by external evaluators.Knowledge tests were scored by traditional criterion-referenced measures, where there is a ‘right’ answer to each question, and a ‘wrong’ answer, yielding a percentage of correct responses. However, knowledge-test outcomes were analyzed more as norm-referenced measures of individual achievement where the percentage correct (regardless of the baseline) was not measured against a pre-determined standard (i.e., grading scale) but rather against their own [pretest] score for signs of improvement in their performance on content knowledge assessments. Different measures were used for each exchange with results from the first exchange demonstrating football (12 items) and peace (2 items) knowledge, while the second exchange included measures with a more balanced curricula (4 football skills related items, 5 peaceful living skills related items).

Responses to the mutual understanding and perceived abilities items were considered relative to the 2.5 best-practice standards indicating item agreement; if the remaining decimal fraction is greater (>) than 1/2 unit of measurement, it is necessary to round and to increase the preceding digit by 1. In this practice, a 2.5 is necessary to equate to “agreement” or a “3” as represented on the Likert-scale. Responses were then recoded according to those that met “agreement.” The total number of participants who met the standard was then recalculated as a percentage of the whole.

Non-parametric tests and inferential analyses were used to examine individual subject differences that were observed between pre/post-test scores. Gains in mutual understanding were analyzed through participants’ paired pre/post-test responses to social distance scale items.

Results

The study’s focal point were the results determining individual participant increases in observed scores of content knowledge (including overall improvement on the post-test, and improvements on the post-test items specific to football content and peace curricula), observed decreases in social distance scores (indicating increased mutual understanding), and measures of participants’ self-perceived preparedness and confidence to apply the taught skills.

First, determining the characteristics of the distribution was a critical step in the post-hoc selection of the appropriate test statistic. Results of a skewness test did not reveal normal distribution for any of the pre/post-test data associated with the project’s two success metrics: knowledge gains (including overall [football plus peaceful living skills] scores; content-specific [football or peaceful living skills] scores; and mutual understanding (social distance items), which were found to violate normality. Neither a Log-10 transformation nor a square root transformation distributed this positively skewed data normally; thus, the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was determined as the most robust selection for this series of analyses. Due to the normality violation, nonparametric tests were utilized for further analysis.

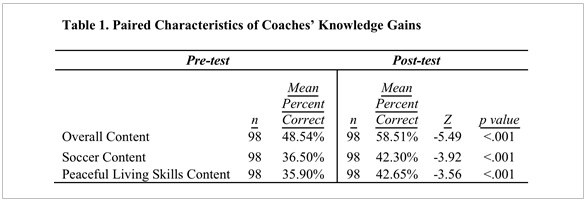

Results of a Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test indicated that there was a significant increase in the coaches’ overall (football plus peaceful living skills) post-test performance, Z = -5.49, p < 0.001. Similarly, content-specific comparisons of coaches’ pre/post-test performance followed this trend where football content achieved a significant increase on the post-test (Z = -3.92, p < .00) as did content that was related to peaceful living skills (Z = -3.56, p < .00). These results suggested that the programme increased performance on the post-test or knowledge gains achieved among coaches (see Table 1).

Results of a Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for mutual understanding indicated that only the last item, (“I feel comfortable when working with someone of the opposite gender”), achieved significance, Z = -1.95, p = .05. Thus, coaches were more comfortable working with the opposite gender after engaging in the programme. Pre- and post-programme means for each social distance item appear in Table 2.

To operationalize the efficiency and effectiveness of the programme, coaches were asked to consider “preparedness” and “confidence” relative to coaching tactical and technical football skills, promoting physical fitness and developing citizenship behaviours and peaceful living skills among youth. These constructs of preparedness and confidence are based on the attributional theory of achievement motivation. Weiner’s41 work identifies behavioral preparation and self-confidence as the dominant achievement attributes in motivating others. The Jordanian coaches’ ability to replicate and incorporate lessons learned (football and peaceful living skills) into their personal coaching style were largely operationalized based on these motivational constructs. The theory also accounts and allows for emotion as a causal factor to motivation, not a bias. In this case, for example, the self-reported items related to “feeling prepared and/or confident” are considered dominant attributes and not social desirability.

Items were collapsed into a single compendium score of coach “preparedness” to implement football-related and peaceful living skills into their coaching. Results indicated that 88% (n = 88) of the coaches reported feeling prepared to implement the football skills highlighted in the programme into their coaching (vs. 12%, n = 12). The subscale (see Table 3) focused on coaches’ “preparedness” regarding football-related skills, which included five items (α = .53). All coaches who responded to the peaceful living skills items indicated preparedness to implement these skills into their coaching (100%, n = 103). The subscale designed to assess coaches’ peaceful living skills “preparedness” included five items (α = .61). These less robust observations of internal consistency related to these items may be due to the variable levels of coaches’ experience.

Results for the self-reported “confidence” items indicated that nearly 93% of the coaches (number of participants that met 2.5 standard recalculated as a percentage of all participants) were confident regarding their ability to integrate football-related skills into their coaching that was highlighted in the current programme (n = 90). The subscale (see Table 4) focused on coaches’ confidence to implement football-related skills included seven items (α = .77). Again, 100% of responding coaches were confident that they could integrate peaceful living skills content into their coaching (n = 98). The subscale designed to assess coaches’ confidence to implement peaceful living skills included eight items (α = .80).

Participant satisfaction also was considered to be a critical part of the evaluation process. The subscale related to coaches’ satisfaction with football-related content consisted of five items (α = .83) with almost 91% (n = 90) of the coaches indicating positive ratings of satisfaction with the football-specific content and its delivery. Peaceful living skills content and delivery was also very positively rated (across the six related items [α = .63]) with 100% of responding coaches (n = 102) indicating satisfaction with this aspect of the programme (see Table 5).

Discussion and Implications

This SDP programme utilized a sport-plus, train-the-trainer approach whereby trained coaches returned to their communities to teach athletes peace building and conflict resolution through football. The approach was grounded in theory from sport for development, social learning, sport psychology, youth development and leadership. Overall, the findings provide support for the success of the SPUJ programme as well as ideas for future programme development.

Programme Evaluation

Results indicated that from the programme’s beginning to its conclusion, coaches increased their content knowledge and also became more willing to work with someone of a different gender. The majority of coaches also reported feeling prepared and confident in their ability to use their newly learned skills and satisfied with their training overall. Upon more in-depth analysis of the data, it became apparent that the coaches’ knowledge levels were only moderately improved. However, these findings were not surprising given the abbreviated amount of time coaches spent learning various football and peaceful living skills in the programme. After the first stage of the programme, results indicated that participants failed to transfer connections between the general subject of football and peaceful living skills. Thus, the results suggested the workshop taught football and peaceful living skills, not football with peaceful living skills. In order to achieve educational objectives, the lessons on the football field needed to be applicable to situations outside of the football field. Modifications were subsequently made to the second training in Jordan to allow coaches to participate in four days of training and spend more time integrating football with peaceful living skills. Data indicated that adequate attention was given to each singular subject and how they could converge to promote strong citizenship and peaceful living skills through the game of football.

Inconsistent with expectations and in contrast to the knowledge gains achieved by coaches through their programme participation, no change occurred in four out of the five coaches’ self-reported mutual understanding and social distance responses (i.e., comfort when talking to, working with, living next to, or being supervised at work by people from another culture). Perhaps there was not enough time for enculturation considering the first training session was only two days long and the second session just four days.42,43 Additionally, these workshops did not include direct activities to promote mutual understanding, rather it was indirectly addressed through team-building activities and group work. Clearly, merely participating in a sport was not enough to increase mutual understanding.6,7

Coaches did report, however, increased mutual understanding on one item related to comfort when working with someone of the opposite gender. From a cultural perspective, this result is noteworthy, as women and men do not work together regularly in many contexts in Jordan, suggesting that it is possible to promote egalitarian activities between genders at least in the context of football. While this was not a direct topic of conversation during the training, both the project director and one of the lead soccer instructors from the SPUJ programme were women. Perhaps, this modeling of interaction might have demonstrated another approach to gender work-based interaction. Parents, community members, and religious leaders have expressed widespread concern with female participation in sports, which is a common theme in other international SDP programmes.20,22

It is notable that it was a challenging task to accurately measure mutual understanding under short-term circumstances and interventions in this programme. Bias also was introduced, as questionnaires were confidential but not anonymous due to its design. It was difficult for the programme to facilitate a significant increase in mutual understanding through a short workshop measured through a pre/post-test quantitative design. Scores improved as participants spent more time with key project personnel as was the case in the latter exchange. It is recommended that statements in future projects be specific to interactions such as “through this training, I learned to work with others from different cultures.”

The next set of findings provided stronger support for the programme’s effectiveness. At the conclusion of the programme, 88% of the coaches stated they were prepared to incorporate the football skills they had learned into their coaching and 100% reported being able to incorporate the peaceful living skills learned during the programme. Furthermore, after completing the programme, the coaches were confident about their ability to teach the football and peaceful living skills they had acquired through the programme. More specifically, 93% of the coaches reported being confident with respect to the football skills, and 100% in terms of the peaceful living skills. These results suggest the participant coaches thought that they had the knowledge, ability, and self-efficacy to teach what they had learned to their athletes. Coaches were also very satisfied with the programme, reporting high positive ratings for the football (91% of coaches) and peaceful living (100% of coaches) content addressed in the programme.

SDP Programme Development

From a SDP programme development viewpoint, several lessons were learned that led to some modification between the first and second training sessions and to recommendations for future programmes. Lessons learned included methods to better integrate content and application, address organizational change and consistency in evaluation.

Based on the current findings that will enhance learning, future curriculum must include a balance of technical content alongside the programme’s application or experiential components, which includes effective methods to deliver both components. Focus needs to be placed on each of these components individually. Much more time needs to be devoted to coaches practicing the desired behaviours. Future projects need to give greater consideration to developing curriculum that blend topic areas cohesively so that coaches’ lessons of these critical “life skills” are seamlessly integrated with the football practice exercises employed in culturally applicable ways; Coalter22 and Sugden18 recommend this approach as well. Lyras and Peachey5 recommended inclusive and collaborative programming among expert groups and stakeholders, which may assist with this integration in culturally relevant ways. Furthermore, experiential activities combined with didactic presentations in real-time seems to be appealing to coaches, who tend to be action and movement-oriented. It is also important for future programmes to integrate break times that include physical movement and “fun” activities.

To facilitate adequate learning time, it is important that content is streamlined and the agenda is flexible enough to allow time for interpretation. The first set of workshops involved real-time interpreting on the field and only a few pre-work discussions with the interpreters.45 The time taken to interpret instructions took away from instructional time, leaving some material uncovered. This may have affected the overall satisfaction rating of participants if they were disappointed by the perceived gaps in the material. Allowing more time for interpretation may have helped increase participant satisfaction and knowledge gains.

Future projects may wish to consider revising content lessons, devising a time sensitive agenda, and creating smaller work groups where this is possible.

Another lesson learned was the importance of including deliberate discussion time and goal-setting regarding organizational and sustainable change. This was insufficiently addressed during the first programme exchange due to unexpected delays delivering the content and the limited time in each city. For these reasons, there were no formalized discussions with the Jordanian coaches regarding long-term changes during the first exchange. By altering the format of the second exchange in Jordan, more sufficient time was devoted to sustainability discussions. Through this process, Jordanian coaches were given helpful hints and specific examples in which they could fully implement the skills that they learned into their coaching styles. These discussions are crucial for sustainable change.20,44,45 In Jordan, religious and parental concern over girls participating in sports is a major barrier to sustainable change. This barrier must be addressed without imposing western ideology, so it is recommended that western programme staff collaborate more with in-country partners such as parents in future programmes. For example, this method would better promote the discussion of parental concerns and assure them that the norms and values linked with the Islamic faith will be followed during their daughter’s potential or actual involvement in the programme.18 However, it should be noted that SDP programme staff should be cautious in promoting a western agenda that fosters the participation of women in sport (see Caudwell46 for a more thorough discussion).

Finally, the importance of consistency among instruments is critical. While each programme exchange had its own purpose, the foundation of measurement must be the same, yet maintain a degree of flexibility.46 It is only through consistency of questions and items that longitudinal results can be interpreted. This is especially the case for items assessing “preparedness” and “confidence” constructs. Consistent verbiage related to contextualizing these constructs is necessary to obtain valid data on the percentage of participants meeting the expected outcome. Using diverse items to assess similar constructs across different training sessions makes determining the psychometric properties of composite variables less intuitive, resulting in some subscales with low internal consistency.

Conclusion

SDP initiatives are not only seen as catalysts but as main instruments in positive peace-building strategies. Results from this study show that an international sport-plus SDP programme, which was designed to increase coaches’ ability to use football to teach conflict-resolution skills to their athletes, led to coaches’ satisfying experiences, knowledge gains, confidence in using their newly learned skills, and increased comfort and openness to working interactions between men and women. Utilizing sport as a tool to promote empathy, leadership, communication, peace-building skills and collaboration among diverse populations may provide young athletes with the skill-sets needed to become productive and well-rounded adults who are better prepared to contribute to society. Conversely, the implications of missing an opportunity to capitalize an avenue such as sport in order to initiate social change may result in continued social segregation, fear of other cultures, and the inability to meaningfully interact with those who hold different values and perspectives. In planning future initiatives to impact social development, leaders of organizations need to consider the value of training sport coaches as a vehicle to deliver positive messaging to young people to help shape grassroots development. Additionally, researchers and practitioners might consider further discussion about the debates related to neo-colonialism in SDP work and the impact it has on programmes overall.

References

1. Galtung J. Peace education: Problems and conflicts. In: Haavelsrud M, ed. Education for Peace, Reflection and Action. Guilford: IPC Science and Technology Press;1975:80-87.2. Galtung J. Peace studies and conflict resolution: The need for transdisciplinarity. Transcult Psychiatry. 2010;47(1):20-32. doi:10.1177/1363461510362041

;Titel anhand dieser DOI in Citavi-Projekt übernehmen’/>3. Christie DJ, Tint BS, Wagner RV, Winter DD. Peace psychology for a peaceful world. Am Psychol. 2008;63(6):540-52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.540

;Titel anhand dieser DOI in Citavi-Projekt übernehmen’/>4. Gawerc MI. Peace-building: Theoretical and concrete perspectives. Peace Change. 2006;31(4):435-78. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0130.2006.00387.x

;Titel anhand dieser DOI in Citavi-Projekt übernehmen’/>5. Lyras A, Peachey JW. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Manag Rev. 2011;14:311-326

6. Coalter F. Sports clubs, social capital and social regeneration: ‘Ill-defined interventions with hard to follow outcomes’? Sport in Soc. 2007;10:537-59. doi:10.1080/17430430701388723

;Titel anhand dieser DOI in Citavi-Projekt übernehmen’/>7. Coakley JJ. Sport in society: Issues and controversies. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Irwin/McGraw-Hill; 1998.

8. Lyras A. Characteristics and psycho-social impacts of an inter-ethnic educational sport initiative on Greek and Turkish Cypriot youth. PhD [dissertation]. Storrs (CT): University of Connecticut; 2007.

9. Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954.

10. Maslow A. Motivation and Personality. 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row; 1970.

11. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68-78.

12. Henley R. Helping children overcome disaster trauma through post-emergency psychosocial sports programs (Swiss Academy for Development Report). Biel/Bienne: Swiss Academy for Development; 2005.

13. Conroy DE., Coatsworth JD. Coach training as a strategy for promoting youth social development. Sport Psychol. 2006;20:128-44.

14. Smith RE, Smoll FL, Barnett NP. Reduction of children’s sport performance anxiety through social support and stress-reduction training for coaches. J of Appl Dev Psychol. 1995;16:125-42.

15. Coalter F. Sport for development: What game are we playing? London: Routledge; 2013.

16. Conroy DE, Coatsworth JD. The effects of coach training on fear of failure in youth swimmers: A latent growth curve analysis from a randomized, controlled trial. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2004;25:193-214.

17. Smoll FL, Smith RE, Barnett NP, Everett JJ. Enhancement of childrenʼs self-esteem through social support training for youth sport coaches. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78:602-10.

18. Sugden, J. Teaching and playing sport for conflict resolution and co-existence in Israel. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 2006; 41:221-40.

19. Schulenkorf N, Sugden J. Sport for development and peace in divided societies: Cooperating for inter-community empowerment in Israel. Eur J Sport Sci. 2011; 8:235-56.

20. Pink M, Cameron M. Motivations, barriers, and the need to engage with community leaders: Challenges of establishing a sport for development project in Baucau, East Timor. Int J Sport Soc. 2013; 4:15-29.

21. Whitley MA, Forneris T, Barker B. The reality of evaluating community-based sport and physical activity programs to enhance the development of underserved youth: Challenges and potential strategies. Quest, 2014;66:218-32.

22. Coalter F. Sport for development: An impact study. International Development through Sport, UK Sport & Comic Relief. Stirling, UK: 2010.

23. LeCrom CW, Dwyer, B. Plus-sport: The impact of a cross-cultural soccer coaching exchange. J of Sport Development. 2013;1(2):1-14.

24. Aber JL, Brown JL, Henrich CC. Teaching conflict resolution: An effective school-based approach to violence prevention. 1999. Available at: http://www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/Teaching%20Conflict%20Resolution.pdf

25. Rookwood J. Soccer for peace and social development. J Social Justice. 2008;20:471-479.

26. Wikipedia. Jordan. Wikipedia website. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jordan#cite_note-57. Updated November 20, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2013.

27. CIA. The world factbook: Jordan. CIA website. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/jo.html. Updated November 5, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2013.

28. Embassy of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Washington, D.C. Jordan-US relations overview. The Embassy of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Washington, D.C. website. http://jordanembassyus.org/page/jordan-us-relations-overview. Updated 2013. Accessed November 19, 2013.

29. Wikipedia. Sport in Jordan. Wikipedia website. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sport_in_Jordan. Updated November 5, 2013. Accessed November 11, 2013.

30. Johnston P. Soccer-ambitious Jordan eye World Cup breakthrough. Yahoo News website. http://news.yahoo.com/soccer-ambitious-jordan-eye-world-cup-breakthrough-111905551–sow.html. Published November 11, 2013. Accessed November 14, 2013.

31. FIFA. Country info. FIFA website. http://www.fifa.com/associations/association=jor/countryInfo.html. Updated 2014. Accessed November 11, 2013.

32. Parrillo VN, Donoghue C. Updating the Bogardus social distance studies: A new national survey. Soc Sci J. 2005;42(2):257-71.

33. Bogardus ES. Social distance and its origins. Sociol Soc Res. 1925;9:216–25.

34. Bogardus ES. A social distance scale. Sociol Soc Res. 1933;22:265–71.

35. Bogardus ES. Changes in racial distance. Int J Public Opin Res. 1947;1:55–62.

36. Bogardus ES. Racial distance changes in the United States during the past thirty years. Sociol Soc Res. 1958;43:127–35.

37. Bogardus ES. Comparing racial distance in Ethiopia, South Africa, and the United States. Sociol Soc Res. 1968;52:149–156.

38. Bandura A. Human agency in Social Cognitive Theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44:1175-84.

39. Csikszentmihalyi M, Robinson RE. The art of seeing: An interpretation of the aesthetic encounter. Malibu, CA: J. P. Getty Museum; 1990.

40. Christie DJ, Wagner RV, Winter DDN. Introduction to peace psychology. In: Christie DJ, Wagner RV, Winter DDN, eds. Peace, conflict, and violence: Peace psychology for the 21st century. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2001:1-15.

41. Weiner B. An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion. Psychological Review. 1985; 92(4): 548-573.

42. Amara M, Aquilina D, Henry I, Taylor M. Sport and Multiculturism. Brussels: European Commission, DG Education and Culture; 2005.

43. Langley CS, Breese JR. Interacting sojourners: A study of students studying abroad. Social Science Journal. 2005;42(2):313-321.

44. Burnett, C, Uys, T. Sport development impact assessment: Towards a rationale and tool. J Res Sport, Physical Education, Recreation. 2000;22(1):27-40.

45. Coalter F. Sport and community development: A manual. Edinburgh, Scotland: Research Unit SportScotland;2002.

46. Caudwell J. On shifting sands: The complexities of women’s and girls’ involvement in Football for Peace. In: Sugden J , Wallis J, Eds. Football for Peace: The challenges of using sport for co-existence in Israel. Oxford:Meyer & Meyer Sport;2007:97-112.