Tom Fabian1 and Audrey R. Giles1

1 School of Human Kinetics, University of Ottawa, Canada

Citation:

Fabian, T. & Giles, A.R. (2023). Reviving Culture and Reclaiming Youth: Representations of Traditional Indigenous Games in Mainstream Canadian and Indigenous Media. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Indigenous games are rarely discussed within the sport for development (SFD) realm. Instead, even when SFD interventions are aimed at Indigenous youth, the focus is typically on the use of “modern” (European-derived) sport. We sought to analyze how mainstream and Indigenous media in Canada produce understandings of traditional Indigenous games and how, and if, media discourses reflect the idea of traditional games as a form of SFD. Using databases, we searched both mainstream and Indigenous media sources over a ten-year period from 2011 to 2021, identifying 23 articles pertaining to traditional games. Using critical discourse analysis, we noted the (re)production of two discourses in both mainstream and Indigenous media sources: Traditional games keep culture alive; and Indigenous youth can be “reclaimed” through traditional games. In concluding that similar discourses were produced about traditional games in both mainstream and Indigenous media sources, the manner in which the discourses were produced became a focal point for examination. The Western-centric sports journalism approach to traditional games coverage illuminated a strong SFD ideology within the discourses, despite traditional Indigenous games largely rejecting Western sport logic. Our findings suggest the need to appreciate the differences of traditional games from SFD practices for the purposes of cultural and youth development.

REVIVING CULTURE AND RECLAIMING YOUTH: REPRESENTATIONS OF TRADITIONAL INDIGENOUS GAMES IN MAINSTREAM CANADIAN AND INDIGENOUS MEDIA

As a form of cultural practice, traditional Indigenous games, like other forms of physical culture, are rooted in the norms and values of the communities from which they hail. Importantly, Rice (2019) explained that, in many instances, “traditional teachings are found in the games of Indigenous peoples” (p. 172). They are localized, ethnically-rooted, and reflect the somatic heritage of distinct cultural groups. Traditional Indigenous games in what is now known as Canada include ball games (e.g., lacrosse or doubleball), hoop games, stick throwing (e.g., snow snake), feats of strength (e.g., pole push), jumping contests (e.g., two-foot-high kick), foot or canoe races, hand games, games of chance (e.g., dice games), and myriad other game forms (Robillard, 2019). In many instances, Indigenous games are based on survival skills. For instance, Heine (2006) noted that Dene games, played by the Dene whose traditional territories are in the Sub-arctic in Canada, are heavily influenced by the connection between travel and life on the land; strength, endurance, speed, and accuracy were necessary for travelling and hunting on the land and were often practiced by playing traditional games.

The distinction between traditional games and modern sport is particularly important in terms of the presentation of Indigenous games in the media, the framing of the rapidly growing area of sport for development (SFD) programs for/with Indigenous peoples, and the ways in which Indigenous communities and individuals relate to their games. This distinction is based primarily on determinate structures. Mainstream—also referred to as modern—sport is an organized, institutionalized, and decidedly modern phenomena that is often linked to seven characteristics theorized by Guttmann (1978): secularism; equality; specialization; bureaucratization; rationalization; quantification; and obsession with records. Traditional games, on the other hand, do not have some of these determinate structures, including strict rules and regulations, bureaucratic governance, or gender equality, as noted by Giles (2005a, 2005b, 2008) in her work on Dene hand games. A particularly stark example is the appropriation and transformation of lacrosse from a dynamic, spiritual, Indigenous body culture to an “organized” (in the institutional sense), nationalized, neo-colonial sport form in the mid-nineteenth century (Delsahut, 2015; Downey, 2018; Morrow, 1992). There is a constant tension between the historical colonial “nation-building” processes that thrive upon burgeoning notions of modernity and “traditional” Indigenous culture, which have continued into the present and frame our understanding of traditional games vis-à-vis modern sports.

Since the onset of settler colonialism, however, traditional Indigenous games have been marginalized and, in some cases, extinguished. As Indigenous cultural practices, including games, conflicted with Eurocentric culture, settlers often prohibited these practices. Many Indigenous physical cultural practices were actively suppressed and “discouraged as much as possible, and … replaced with Euro-Canadian sports and games” (Forsyth, 2007, p. 99) in an effort to regulate Indigenous culture in the wake of the 1876 Indian Act, which has had long-reaching repercussions on many aspects of First Nations peoples’ lives, including traditional games participation, in Canada. Indeed, in contemporary arctic Canada, Heine (2014) lamented that “traditional games now occupy a more marginal position in the daily recreational activities of most Arctic and subarctic communities, having to compete for resources, recognition and volunteer personnel with the community recreational sport competition schedules” (pp. 3-4).

Nevertheless, in the last few decades, traditional Indigenous games have seen a revitalization through cultural programming and games festivals (Ferreira, 2014; Heine & Young, 1997; Vladimirova, 2017), which has enhanced media attention. Moreover, since the publication of the reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada (2015), which had an overall objective to “remedy the ongoing structural legacy of Canada’s residential schools and to advance reconciliation” (Jewell & Mosby, 2021, p. 2), there has been a greater onus on academics, the media, and the Canadian public to understand Indigenous cultural practices. For instance, the TRC’s (2015) 90th Call to Action (of 94) demands “access to community sports programs that reflect the diverse cultures and traditional sporting activities of Aboriginal peoples” (p. 10)1. As part of its response, the federal government provided funding to the Aboriginal Sport Circle, the national organization for Indigenous sport in Canada, for a program called “Sport for Social Development in Indigenous Communities,” which fell under the “reconciliation” component of the federal budget. The program’s aim is to help to address the “social development needs of Indigenous communities” through sport (Government of Canada, 2021, para 5). It is here that we see the ways in which sport—including traditional “sports” or games—programs are often expected to have social development outcomes when delivered with/to Indigenous communities. In light of this, in this study, we sought to analyze how mainstream and Indigenous media in Canada produce understandings of traditional Indigenous games and how media discourses reflect the idea of traditional games as a form of SFD.

Sport for Development

SFD refers to the use of sport to address a wide array of social development problems, including but not limited to reducing HIV/AIDS (Nicholls et al., 2011), empowering girls and women (Brady, 2005), and peace building (Schnitzer et al., 2013). Most of the early focus of SFD intervention and research was on countries in the so-called “developing world” (Hayhurst & Giles, 2013). More recently, the gaze has shifted to the ways in which SFD has been employed in the “developed world,” especially with Indigenous peoples. Hayhurst and Giles (2013), however, have argued that SFD is merely a new term for a practice that has a long colonial history. Drawing on the work of Miller (1997) and Forsyth (2013), Hayhurst and Giles pointed out that many of the outcomes that contemporary SFD programs attempt to address (e.g., health, education, and self-improvement) are the very outcomes that Indian residential schools also tried to achieve for their (male) Indigenous pupils through the use of sport. Indeed, development as Westernization or colonialism dominates SFD discourses. For example, increasing the number of Indigenous youths who become good Euro-Canadian-styled leaders is often a desired outcome of SFD initiatives (Galipeau & Giles, 2014; Gartner-Manzon & Giles, 2016, 2018), while outcomes such as enhanced Indigenous self-determination or engaging Indigenous youth in Indigenous cultural resurgence are rarely, if ever, discussed as key components of these programs.

Importantly, traditional games are not often used in, or the focus of, SFD programs. Considering the developmental and even reconciliatory objectives of such programs, one might expect that SFD program providers would champion Indigenous games in Indigenous community programs. Instead, as a neo-colonial entity, SFD tends to employ Western, mainstream, modern sport forms, as opposed to culturally relevant, land-based, traditional game forms. SFD’s lack of engagement with traditional games is likely because traditional games may not fit within SFD colonial logic. By employing the notion of reconciliation in the SFD paradigm, particularly in settler-colonial settings, there may be an opportunity to better engage traditional games. Indeed, Halas (2013) argued that traditional games and land-based physical activities are important to reconciliation, specifically by introducing the meaning of games with teachings of traditional cultures. Summed up expertly by Essa et al. (2021), “highly meaningful, legitimate [SFD] programs” are “supportive of resurgence and decolonization … focus on communities’ needs, values and worldviews; they integrate sport and recreation-based activities grounded in more holistic views of health and wellbeing; and most importantly, they are land-based” (p. 308). Such an approach foregrounds the importance of Indigenous peoples’ relationships with the land. With these tenets in consideration, there may be a number of reconciliatory pathways for the community support of traditional games. However, one of the most important focus areas is the (lack of) media coverage of traditional games. Indeed, what has not been said about traditional games in the media is as crucial as what has been said (Parker, 1992). Focusing on Indigenous games, as opposed to Western sports, may be the crux of future developmental or reconciliatory initiatives within the Canadian SFD landscape. In light of the dominant ways in which SFD has been understood, and the lack of traditional games focus, both mainstream and Indigenous news media coverage of Indigenous traditional games in Canada becomes a compelling site for investigation.

Media Representations of Indigenous Cultures

One way that (neo)colonialism in contemporary Canada is produced is through the media. The Canadian media can be described as regionalized and corporatized. The largest corporation is the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC), the national public television and radio broadcaster responsible for producing cultural content, which mirrors the multicultural and multiracial nature of Canada. CBC radio, television, and online broadcasting reflects Canada’s cultural identity, and the CBC’s cultural narratives are routinely buried behind self-definitions of Canada as tolerant, multicultural, and peaceful (Pegley, 2004), reinforcing dominant colonial subjectivity (and the white hegemonic subject in particular). Newspapers are dominated by several media conglomerates—Postmedia Network (121 newspapers) and TorStar (100 newspapers) own the most daily and community newspapers. The two major national newspapers are The Globe and Mail, considered centre-right in its editorial stance and catering more to the intellectual elite, and the National Post, a more recent (1998) and conservative option. Although considered a local newspaper, the Toronto Star has the largest average daily readership of all newspapers in Canada and is national in scope (News Media Canada, 2020).

Considering the nationalistic imperatives of the CBC, the corporatization of the newspaper industry, and the hegemonic ownership and operation of these media entities by predominantly elite, white, male, settler Anglo-Canadians, it is no surprise that colonial representations of Indigenous peoples and cultures persist in mainstream Canadian media, thus protecting dominant power structures from the threat of Indigenous interests2. Mass media frames are not only influenced by the context, themes, and words used by journalists but also by influential businesses, political leaders, and media owners themselves, creating structural sources of bias that privilege certain perspectives, modes of production, journalistic styles, and what receives (and does not receive) coverage. On many topics and issues, an almost primitivist lens is used by mainstream media to frame Indigenous cultural activities as exotic or authentic—a mode of representation which has widespread consequences (Prins, 2002). Indeed, the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, a report that covered a range of issues, noted that “many Canadians know Aboriginal people only as noble environmentalists, angry warriors, or pitiful victims” (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996, para. 2). Stereotyping of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian media is far from a thing of the past (Beauregard & Paquette, 2021; Clark, 2014; Fleras, 2011, 2012; Harding, 2005). Moreover, in a summative study on the historical representations of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian mainstream news media, Harding (2006) wrote, “although the views of aboriginal people are now routinely included in the news, their impact is diluted through techniques of deflection, de-contextualization, misrepresentation and tokenization” (p. 225). In this regard, the coverage of Indigenous topics by mainstream media has been limited in its ability to provide a balanced perspective (Love & Tilley, 2013). The importance of critical media literacy, in this context, is crucial to distill the negative effects of pervasive colonial media representations of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Following Nemec (2021), we understand Indigenous media as “media made by Indigenous people, that tells Indigenous stories for Indigenous people and hence is as diverse as those who identify as Indigenous” (p. 998). Indigenous-produced content has a distinct Indigenous sensibility in which seeing, hearing, knowing, speaking, and performing are signified and represented (Ginsburg, 1991; Hanusch, 2013). Self-determined Indigenous media coverage in Canada became more prominent during the 1970s and 1980s with the proliferation of Indigenous communications societies (Alia, 2009)—including the Wawatay Native Communications Society (1974), Inuit Broadcasting Corporation (1981), and Aboriginal Multi-Media Society (1983)—culminating with the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network in 1999. These efforts of Indigenous reporting, news outlets, and media have reaped rewards. Not only is such media an assertion of Indigenous identity, but it is also a means of cultural and political intervention in the “mainstream,” and countering the more often than not negative representations of Indigeneity in the media. Nemec (2021) explained that “Indigenous media, as in all alternative media, has a role to play in questioning or challenging accepted thinking and to present counter hegemonic discourses to all citizens in participatory democratic societies” (p. 998). Indeed, there are key differences between Indigenous and mainstream media, and Indigenous media producers use both forms of media to combat discrimination and preserve their cultures and traditions (Jeppesen, 2021; Wilson & Stewart, 2008). As noted by Lowan-Trudeau (2021) in an article about Indigenous environmental media coverage, “the efforts of Indigenous and allied media scholars and practitioners have also begun to influence the ethics and practices of non-Indigenous media and publishing entities in their coverage of Indigenous topics” (p. 93). With this in mind, we were interested in investigating the similarities and differences in mainstream and Indigenous news coverage pertaining to traditional Indigenous games in Canada.

METHODS

Discourse Analysis

Prior to describing our approach to data analysis, it is important to situate ourselves. Both authors are white, non-Indigenous settlers in Canada of European descent. To analyze our data, we used critical discourse analysis. Within the critical discourse analysis, discourse refers to all forms of talk and text and can be understood as providing the meanings that constitute everyday practices (Henriques et al., 1984). Discourse and society are seen in a dialectical relationship, with social structures affecting discourse and discourse affecting social structure. Employing “critical” discourse analysis means that we aim to not only describe discursive practices, but also to show “how discourse is shaped by relations of power and ideologies” (Fairclough, 1992, p. 12). Certainly, issues of power are pervasive in relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, as well as within SFD and traditional games for/with Indigenous peoples. Tuck and Yang (2012) have pointed to the ways in which Indigenous peoples have been produced—in the media, in educational institutions, in government policies—as being “at risk” of a host of issues. Most of what Canadians know about Indigenous issues comes from the mainstream media and research has demonstrated that media discourses have had a great deal of influence over the attitudes of mainstream society towards “racialized” groups (i.e., negative discourses about Indigenous people have the power to negatively influence the general public’s understanding of Indigenous people).

Researchers have shown that media reporting on SFD appears to reinforce racist, colonial discourses concerning Indigenous people in Canada; in particular, researcher have found that media portrayals of SFD programs may perpetuate inequalities in marginalized communities by focusing on “deficit-based” discourse and by focusing on the role of “improving” health and conduct rather than challenging the power relations underpinning marginalization and inequality (Coleby & Giles, 2013). It is therefore important to consider how both Indigenous and non-Indigenous media representation of SFD and Indigenous games reproduce and/or challenge (neo)colonial discourses concerning Indigenous peoples.

Producing Indigenous peoples, and especially youth, as being at risk has been used to justify the targeting in SFD programs, including those funded by the Government of Canada. The government’s Sport for Social Development in Indigenous Communities program has four targets, including “reduced at-risk behaviour” (Government of Canada, 2020, para, 5). In examining media coverage of a SFD program in northern Ontario, Coleby and Giles (2013) noted that sport was discursively produced in mainstream media as a way of “saving” Indigenous youth and that the reporting focuses on Indigenous communities’ apparent deficits. Importantly, however, the authors found that Indigenous news sources produced discourses that focused more on Indigenous communities’ strengths. When examining texts about sport, traditional games, and Indigenous peoples, critical discourse analysts thus must ask specific questions, such as those posed by Parker (1992): “Why was this said and not that? Why these words, and where do the connotations of the words fit with different ways of talking about the world” (pp. 3-4). As noted in the previous section, themes and texts used in the media can influence, shape, and reflect unequal power relations.

Sample

We identified news articles from both mainstream and Indigenous media sources: the top national television broadcasting news websites, the top three national newspapers, and ten regional news sources—selected based on geographic representation and readership—for both mainstream and Indigenous news sources. We selected regional news sources based on their national scope, re-printing in national newspapers, and readership. In the mainstream category, the CBC’s website was a valuable resource, as it featured a number of articles on Indigenous games. We also selected the Toronto Star, the Globe & Mail, and the National Post, the three largest national-scope newsprint media by circulation numbers. In addition, regional mainstream news sources consulted included The Chronicle Herald (Halifax), Hamilton Spectator, Montreal Gazette, Northern News Services (an umbrella organization for six weekly northern newspapers: NWT News/North, Nunavut News, Yellowknifer, Hay River Hub, Inuvik Drum, and Kivalliq News), Nunatsiaq News (Nunavut and northern Quebec), Ottawa Citizen, Vancouver Sun, Winnipeg Sun, and Winnipeg Free Press. To note, although both Northern News Services and Nunatsiaq News provide reporting for many predominantly Indigenous communities in the Canadian Arctic and Sub-arctic, based on our criterion for Indigenous news sources, which required Indigenous news services to be owned and operated by Indigenous stakeholders, these two news services were categorized as mainstream.

In the Indigenous media category, we identified Indigenous news sources and corroborated them through three university library catalogues: University of British Columbia, University of Toronto, and Ryerson University. As the only Indigenous national television broadcasting company, we selected the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network for this category of news source (web articles). We also included the top three nationally focused Indigenous news sources: Windspeaker, Turtle Island News, and First Nations Drum3. The regional Indigenous news sources we consulted included Anishinabek News (Union of Ontario Indians), the Eastern Door (Kahnawake, Quebec), Ha-Shilth-Sa (British Columbia), Ku’ku’kwes (Atlantic Canada), Mi’kmaq Maliseet Nations News (Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), Métis Voyageur, Two Row Times (Six Nations, Ontario), Wawatay News (northern Ontario), as well as the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society’s Alberta Sweetgrass and Saskatchewan Sage.

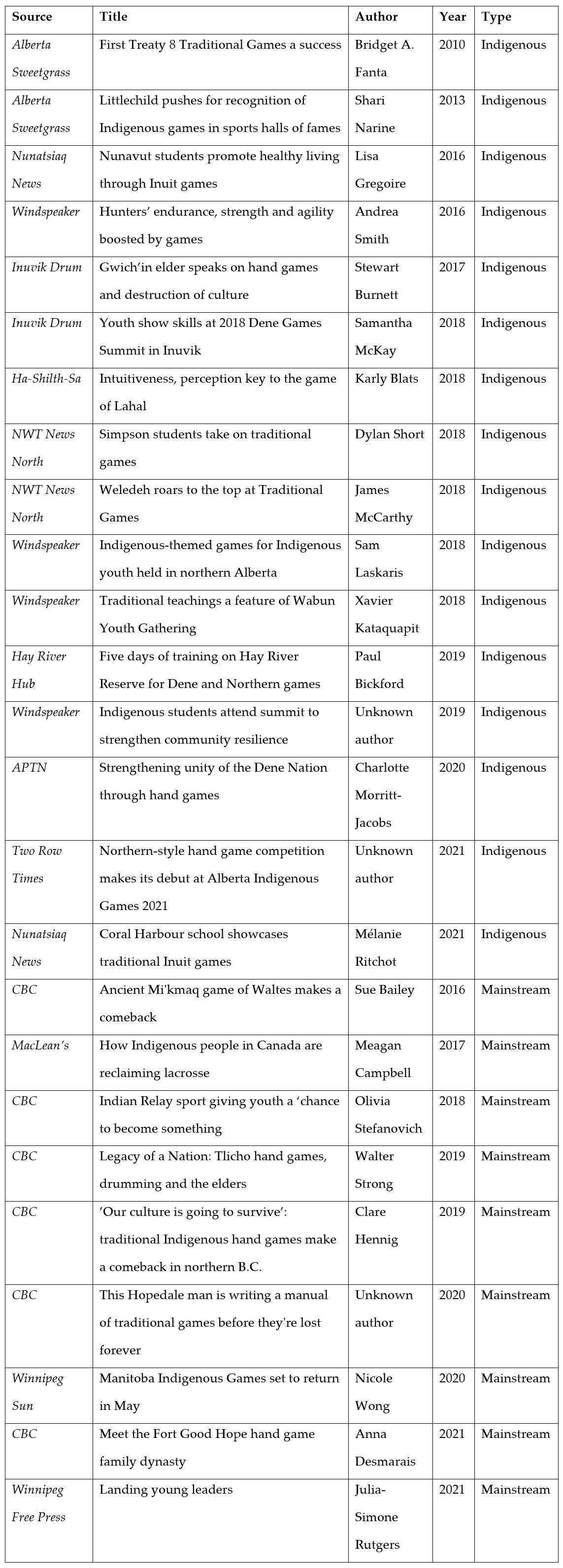

We used the ten-year period from 2011 to 2021 to narrow the focus of the study on more recent developments in media discourse. We used the key search terms “traditional games” and “Indigenous traditional games.” The 23 articles (Table 1) mentioned or discussed Indigenous traditional games at length. To note, we did not include references to the Arctic Winter Games or North American Indigenous Games in this study, as the articles we identified on these topics were informational (dates, results, names) and did not provide meaningful content (i.e., interview quotes or commentary) about traditional games. We read accessed all news articles through each source’s website.

Table 1 – Overview of articles

Overview of Articles

We begin with a descriptive overview of the articles that we included for analysis to promote readers’ understandings of the games prior to sharing the results of our discourse analysis. Of the 23 articles we reviewed, 15 were from mainstream news sources and eight were from Indigenous news sources. Notably, there were no mentions of Canadian Indigenous traditional games in the Globe & Mail, Toronto Star, or National Post during the ten-year period investigated. The only article concerning traditional games (Nolen, 2019) that appeared in the Globe & Mail, which boasts one of the largest subscription bases in Canada (News Media Canada, 2020), was about the resurgence of the ancient Mesoamerican ball game ulama in Mexico. Additionally, only the two northern and two Winnipeg-based mainstream news sources published articles about traditional games during the period studied.

It is unsurprising that the crowded sports sections of mainstream newspapers made no mention of traditional games, as they are often not considered sports (Parlebas, 2020). The majority of the mainstream news stories (six) about traditional games were from the CBC (Bailey, 2016; CBC News, 2020; Desmarais, 2021; Hennig, 2019; Stefanovich, 2018; Strong, 2019) and five (Bickford, 2019; Burnett, 2017; McCarthy, 2018; McKay, 2018; Short, 2018) fell under the Northern News Service umbrella. In the Indigenous news category, two of the three Indigenous national newspapers (Turtle Island News and First Nations Drum) also did not publish articles about traditional games during the ten-year period, nor did a majority (7/10) of the regional Indigenous news sources. Windspeaker (Kataquapit, 2018; Laskaris, 2018; Smith, 2016; Windspeaker, 2019) and its affiliate, Alberta Sweetgrass (Narine, 2013), published five articles dedicated to traditional games.

Eleven of the 23 articles (three mainstream sources and eight Indigenous sources) reported on Dene or Inuit games. Two articles focused on Dene games training camps: McKay (2018) reported on the sixth annual Dene Games Summit in Inuvik, NWT; while Bickford (2019) described a similar event in Hay River, NWT. The articles about Inuit games were somewhat more diverse: Gregoire (2016) described a traditional games program for Nunavut youth in Ottawa; Smith (2016) interviewed an Inuk traditional games athlete and cultural educator about the links between Inuit games and survival skills; and Ritchot (2021) reported on a traditional games kit designed by school teachers and Elders in Coral Harbour, Nunavut. The remaining six articles focused specifically on Dene hand games (Blats, 2018; Desmarais, 2021; Hennig, 2019; Morritt-Jacobs, 2020; Strong, 2019; Two Row Times, 2021). Hand games is a team activity in which one team tries to bluff, jest, and deceive another team by hiding a single small object in their hands to the accompaniment of rhythmic drum music (Bussidor & Bilgen-Reinart, 2000). As can be gleaned from this majority of articles, there has been an increased focus on hand games in recent years, which was the specific focus of Hennig’s (2019) article for the CBC, which reported on the revival of the game in northern British Columbia. The article by Blats (2018) in Ha-Shilth-Sa, a newspaper published by the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council, was a more descriptive piece on lahal (a British Columbia variant of hand games). The article in the Two Row Times, a Six Nations publication, reported on the inclusion of hand games in the 2021 iteration of the Alberta Indigenous Games. The other three articles about hand games (Desmarais 2021; Morritt-Jacobs 2020; Strong 2019) reported on the meaning of hand games amongst the Dene people of the NWT. Interestingly, both Morritt-Jacobs (2020), writing for the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, and Strong (2019), writing for the CBC, covered hand games in the Tłı̨chǫ Nation, specifically since the inception of high-stakes tournaments for men by the Tłı̨chǫ government in 20054.

Outside of Dene or Inuit games, the twelve remaining articles covered an array of topics about traditional games. Narine (2013) interviewed Wilton Littlechild, founder of the Alberta (1971), North American (1990), and World Indigenous Games (2015), about the inclusion of Indigenous traditional games in sports halls of fame5. In the only article focused on Saskatchewan, Stefanovich (2018) reported on the (re)introduction of Indian Relay, a bareback horse-racing relay event, to the area and its effect on Indigenous youth’s self-identity. Burnett (2017) interviewed Fort McPherson, NWT, Elder Charlie Snowshoe about the loss of traditional games, while Wong (2020) reported on the inclusion of traditional games within the Manitoba Indigenous Games programme. An article by the CBC (CBC News, 2020) focused on the work of Boas Mitsuk in compiling a traditional games manual by interviewing Elders in Newfoundland and Labrador. Three articles (Laskaris, 2018; McCarthy, 2018; Short, 2018) focused on Traditional Games Championships in the Alberta and the NWT school systems, while three articles (Kataquapit, 2018; Rutgers, 2021; Windspeaker, 2019) only briefly mentioned the inclusion of traditional games in Indigenous youth summits. Finally, Bailey (2016) reported on the “comeback” of the Mi’kmaq bowl-and-dice game of Waltes in the Maritimes.

The articles covered Indigenous games in seven of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada—BC, NWT, Nunavut, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia. Based on this geographic distribution, the focus on Indigenous traditional games seems to be in the Western, Northern, and Eastern regions of the country, with surprisingly no mentions in Central Canada (Ontario and Quebec), a region of Canada that encompasses over 60% of the population, including about one third of the Indigenous population of Canada. In terms of dates of publication, one article was published in 2010, one in 2013, three in 2016, two in 2017, seven in 2018, four in 2019, three in 2020, and four in 2021. Based on these dates, the temporal distribution of the articles is skewed towards the last five years, with 20 of the 23 articles published since 2017. The outbreak of COVID-19 likely decreased opportunity for many traditional Indigenous games to be played from 2020 onwards due to restrictions on gathering that were put in place across Canada to decrease transmission.

RESULTS

Traditional Games Keep Culture Alive

The first discourse apparent in both Indigenous and mainstream news sources is the notion that traditional games keep culture alive. The “keeping culture alive” discourse was equally represented in both Indigenous and mainstream media, apart from two CBC articles (Bailey, 2016; Hennig, 2019), which leaned on the trope of cultural revival. As opposed to keeping culture alive (or continuous), cultural revival is the notion that traditions, rituals, and customs that are no longer practiced can be reintroduced as a novel yet indistinguishable cultural form.

The discourse of keeping culture alive through games was an important touchpoint in the news articles from Indigenous media. In an interview, a traditional games athlete stated, “it’s important to learn Inuit culture and keep it alive. It’s strong in different places, but like everything else, it’s getting modernised” (Smith, 2016, para. 17). The promotion of culture via traditional games can also be seen in an Alberta Sweetgrass article (Narine, 2013) about the Alberta Indigenous Games, a week of competitive sports, traditional games, special events, and cultural education for Indigenous youth in Alberta. In the article, Wilton Littlechild commented that “in order to reignite our (Alberta) games, we’re heavily involved now in promoting culture and traditional teachings plus the sports” (Narine, 2013, para. 6). Indeed, the authors of articles in Indigenous news sources highlighted the ways in which traditional games can promote culture, by ostensibly advertising it, but also keeping culture alive through participation and repetition.

Within the mainstream news articles, the “keeping culture alive” discourse was similarly strong, especially as quoted from Indigenous interviewees. Comments on keeping their “ancestors’ cultural practices alive” (Desmarais 2021, para. 10) and preventing “the games from dying out” (CBC News, 2020, para. 13) were prevalent. In Short’s (2018) article, Carson Roche, an Aboriginal Sport Circle (ASC) program coordinator, summed up this particular discourse quite aptly when stating, “this is what our ancestors did, and we want [youth] to know it’s part of our culture and we’re trying to keep these games alive” (para. 11). Mainstream news sources emphasized traditional games’ role in cultural vitality. Traditional games that have declined “over the last century with the cultural onslaught of residential schools, television and computers,” noted Bailey (2016), are being revitalized again as Indigenous peoples “increasingly seek out customs that once tightly bound their communities” (para. 6).

Tony Rabesca, a cultural practice manager with the Tłı̨chǫ government in the NWT, underscored the fact that hand games allowed “for healing and full participation in Tłı̨chǫ community life” (Strong 2019, para. 17), a “way of life based on respect for what elders have passed down through uncountable generations” (para. 21). This rendering of cultural vitality through traditional games was an integral aspect of this discourse and of the mainstream articles in general. In this vein, Colin Pybus, the 2018 Dene Games Summit organizer, conveyed that traditional games are “an awesome opportunity for family and friends to get together and share in this amazing aspect of the two Indigenous cultures that are inherent to the area that we live in” (McKay 2018, para. 5). He further remarked that “being able to live one’s culture and compete in that environment … I can only imagine the pride and the desire to do games like this” (McKay, 2018, para. 3). Emphasizing a sense of strength and unity through traditional games, Tyson Head remarked that the Indian Relay promotes “nations all running together and becoming as one” (Stefanovich, 2018, para. 8). Similarly, Ritchot (2021) noted that “games help build a sense of pride in being Inuk” (para. 13). As can be gleaned from the mainstream articles, many Indigenous communities experience a sense of community healing, pride, and unity through traditional games and the communal values inherent to them. Interestingly, the notion of community revitalization not a theme that was not found within Indigenous media.

Reclaiming Youth through Traditional Games

Both mainstream and Indigenous news sources paid particular attention to the role of Indigenous youth in traditional games. The mainstream articles noted the importance of traditional games tournaments for Indigenous youth. For instance, Desmarais (2021) wrote, “as more youth tournaments were organized, more and more young men … started to gravitate to [traditional games]” (para. 13). Similar to the previous discourse, intergenerational knowledge of traditional games was also apparent in the mainstream news coverage. Steve Cockney Sr., an Elder from Inuvik, commented that “we hope that they can carry on throughout the years and pass it on to the next generation” (Bickford, 2019, para. 16). Shawna McLeod, community development manager for the NWT arm of the ASC, noted that “people are really excited to bring [these games] back to their communities … People want to bring it back to introduce it to the youth” (Bickford, 2019, para. 5), as they provide a way for youth to “connect to their roots” (para. 11). Further, Boas Mitsuk, a traditional games coordinator with the Newfoundland and Labrador division of the ASC, explained his mission to compile a traditional games manual as hoping to “bring these games back, that we can get the youth involved, so that we can keep that tradition” (CBC News, 2020, para. 3). In this sense, the “reclaiming youth” discourse intersects with the “keeping culture alive” discourse, as the engagement of youth in traditional games both connects them with their culture while simultaneously keeping culture alive through intergenerational knowledge transmission.

In the mainstream news, traditional games were also produced as being an ideal site for reclaiming Indigenous youth by fostering a sense of belonging, Indigenous self-identity, and cultural pride. In commenting on the importance of connection to the land and traditional culture, Rylee Nepinak, founder of the Winnipeg volunteer group Anishiative, observed that “a lot of youth lacked a sense of belonging. They lacked learning their culture and they didn’t have a connection to the land, and mother earth, and I think that’s so important” (Rutgers, 2021, para. 5). Indian Relay national champion Tyson Head noted that the sport gave “the youth a chance to become something” (Stefanovich 2018, para. 13). In general, many of the mainstream articles reflected the sentiment that such games, and the preparation for them, would “help youth explore their Indigenous self-identity as well as create meaningful internal connections” (Wong, 2020, para. 13). The connection between traditional games participation and youth engagement in pro-social activities—thus presumably keeping them away from anti-social activities—as well as the need for intergenerational knowledge transmission were key components of the discourse about the importance of youth in traditional games.

Traditional games tournaments for Indigenous youth were also a regular topic in the Indigenous news articles (Laskaris 2018; Morritt-Jacobs 2020). Alfonz Nitsiza, Chief of Whatì, in the NWT, commented on the power of youth tournaments in Morritt-Jacobs’ (2020) article: “We are trying to keep it alive … and really encourage younger ones with youth tournaments. It is part of our culture, we lost quite a bit in the past, so it is good to have it back” (para. 4). Deen Flett, who has coordinated multiple traditional games days for Indigenous schools in Alberta, commented that “it is vital to stage Indigenous-themed games for Indigenous youth” (Laskaris, 2018, para. 9). As noted by Laskaris (2018), in Alberta, “these Games were staged to create awareness and promote Indigenous cultures and values in the youth” (para. 4). The authors of the articles in Indigenous news sources produced a discourse that traditional games tournaments are a means for youth to reconnect with their culture. For instance, Kataquapit (2018) described how Lamarr Oksasikewiyin, a traditional knowledge keeper and teacher from Sweetgrass First Nation, Saskatchewan, introduced youth to traditional games and activities at a Wabun Youth Gathering for senior youth in Elk Lake, Ontario. An article in the Two Row Times (2021) also highlighted the importance of traditional games to youth, explaining that the mandate of the Alberta Indigenous Games is to “reclaim our youth through sport development, educational empowerment, career opportunities, and cultural connection” (para. 4).

DISCUSSION

Through the 23 articles reviewed in this study, two key discourses were (re)produced and reflected by mainstream and Indigenous media sources. The first discourse maintained that traditional games—or, more specifically, participation in traditional games—keep culture alive. The notion of cultural continuity was prevalent in this discourse, specifically through the engagement and empowerment of youth through traditional games. As implied by this discourse, like all cultural activities, the only way in which to safeguard their continued practice is by engaging the next generation, thereby keeping the culture alive. The second discourse positioned youth as key guardians of traditional games and traditional games as being key sites for youth culture and identity development, as well as ways to give youth an alternative to their supposed participation in anti-social behaviours. This line of thinking is informed by SFD ideology that situates sport as a “hook” to engage deviant youth in cultural programming (Coakley, 2011). Notably, the results of our investigation found that discourses produced in both Indigenous and mainstream media coverage of traditional games (re)produced similar understandings of traditional games. Given the comparative nature of this study, we initially expected to identify noteworthy divergences between Indigenous and mainstream media coverage of traditional games in Canada. This was not the case; rather, the coverage of traditional games tended to be uniform, taking a Western-centric sports journalism approach (Boyle, 2006), and the discourses that were (re)produced had negligible differences in that both mainstream and Indigenous media portrayed traditional games in similar ways. This may be due to several reasons, including editorialization, local media coverage, or the framing of traditional games as sports.

In terms of editorialization, we are referring to the positive responses of interviewees, as opposed to the editorial decisions of individual news outlets. For instance, people attending events (whether participants or administrators) tend to promote their events, especially when interviewed by the media, which leads to boilerplate platitudes about the mission and positive outcomes (to participants and community) of the event (Schulenkorf et al., 2011). Such platitudes can also be ascribed to interviews about SFD programming and the optimistic lens through which sport contributes to “value education” (Whitehead et al., 2013). Moreover, this sport event or program promotion approach can be construed as a pragmatic usage of discourse by organizers of Indigenous events. In this sense, Indigenous communities are producing the discourses—traditional games keep culture alive and reclaim youth—that news outlets are merely re-presenting and reproducing, without producing a new discourse in and of themselves. This may result in a lack of nuance in understandings of traditional Indigenous games. Moreover, we must also consider that journalistic conventions, often attributed to Western modes of media production and training, can shape representations and reflect a Western worldview even in Indigenous media.

A second contributing factor to negligible differences in mainstream and Indigenous media discourses may be the local, as opposed to national, mainstream media coverage of traditional games. Indeed, an interesting result from Gardam and Giles’ (2016) study, which focused on media representations of Indigenous educational policies, pointed to the ways in which local non-Indigenous media “mirrored” (p. 9) discussions in Indigenous media about the need to address colonial legacies. Although this was not the focus of their research, and thus they recommended future research on the matter, they did note that the readers of local non-Indigenous media—in their case, the Chronicle Journal (Thunder Bay)—“have a stronger relationship to the [Indigenous] issues that occur in Thunder Bay” (p. 7). Many of the mainstream news sources that reported on traditional games in this study were local news services and the discourses presented in the articles examined mirrored those within Indigenous new sources. Perhaps the closeness and sensitization to the issues, as illustrated by Gardam and Giles (2016), is a reason for such similar viewpoints between local mainstream and Indigenous media.

The third contributing factor may be the lack of distinction between Indigenous games and mainstream sports in the reporting. One of the key reasons for the Western-centric sports journalism approach to all the articles is the Western sporting framework that is used to frame both Indigenous and mainstream media stories about sport and traditional games. Both types of media tended not to differentiate between mainstream sports and traditional games. Indeed, the language used to describe mainstream sport was, in the case of the mainstream media, applied to traditional games. The incorporation of “sport” is only one aspect of a “wholistic” (Lavallée & Lévesque, 2013, p. 208) understanding of traditional games by Indigenous peoples; other aspects may be considered the health, culture, social connection, or spirituality of traditional games. Yet, those dimensions were missing from both sets of reporting.

There are important tensions that exist within the notions of Indigenous cultural restoration and revitalization (Corntassel & Bryce, 2012; Scott & Fletcher, 2014). Handler and Linnekin (1984) aptly summarized these tensions: “one of the major paradoxes of the ideology of tradition is that attempts at cultural preservation inevitably alter, reconstruct, or invent the traditions that they are intended to fix” (p. 288). Indeed, to safeguard in a contemporary setting is to imbue the element of cultural heritage—games, in our case—with contemporary qualities. Examples abound in the context of Indigenous multi-sport events, in which traditional games, such as the Dene game stick pull at the Arctic Winter Games, are included in predominantly Western sport programmes, thus transposing traditional games “from a habituated, lived experience into an object of conscious political intervention, transforming them into a ‘museum piece’ in the process” (Mrozek, 1987, p. 38) and conforming them to the norms of the dominant culture’s sporting system. One of the reasons why traditional games have been ignored within the SFD framework is because of its adherence to the hegemonic position of the Western sport model. As a result, traditional games often fall within the sphere of cultural—as opposed to sport—programming and, indeed, the articles investigated alluded to the promotion of culture via traditional games as an important means to keeping culture alive.

Cultural Revival

The beginning of the revival—or increased awareness—of Indigenous games in what is now known as Canada fell within a broader global Indigenous resurgence (Hall & Fenelon, 2009). As noted by Heine (2014) in his discussion of Dene games, “the aboriginal [sic] political activism of the 1970s … led to … a renewed concern for the strengthening of cultural practices; aboriginal games and physical activity practices came to be influenced by these developments” (p. 3). Indeed, the Arctic Winter Games, Alberta Indigenous Games, and Mi’kmaw Summer Games (Nova Scotia) were all also founded during the 1970s, which informed the development of the North American Indigenous Games in 1990. The groundwork of these multi-sport events is a telling development of Indigenous voices being asserted. Yet, the threats to Indigenous cultures in Canada have exposed the ways in which colonialism informs traditional games. Dubnewick et al. (2018) explained that a part of the colonial process “is the discrediting of traditional Indigenous games in public discourse around what is an appropriate and legitimate form of sport and physical practice” (p. 219). SFD ideology, along with media coverage, reinforces the universal position of Euro-centric sports over Indigenous traditional games, even though Indigenous communities may position them differently (Paraschak, 1998).

In an effort to understand the relationship(s) between Indigenous games and discourses of revival, it is important to understand the loss of culture in the first place. Edwards (2009) noted that “usually the first activities ‘suspended’ when a culture comes under threat are the traditional games that require inter-group interactions or are associated with certain social and cultural practices” (p. 35). Indigenous cultures have suffered systematic and systemic erosion since settler contact—from cultural appropriation (Mackey, 1998) to the residential school system (Milloy, 1999) to the homogenizing influence of Western culture (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015). Within this cultural milieu, traditional games tend to be marginalized in lieu of settler sports. For this reason, many of the news articles investigated framed the revival of traditional games as a means of keeping culture alive, as opposed to a facet of a continuous games culture.

Keeping culture alive, or safeguarding traditional games, falls between the notions of cultural continuity and cultural revival. In this sense, change in Indigenous culture is at the core of this discourse. Nagengast (1997) explained that

“culture” is not a homogenous web of meanings that a bounded group creates and reproduces and that can be damaged by change, but, rather … “culture” is an evolving process, an always changing, always fragmented product of negotiation and struggle that flows from multiple axes of inequality. (p. 356)

There are two sides to this discussion on cultural change. On the one hand, cultural continuity refers to a fluidity or evolution of culture. On the other hand, cultural revival supposes a discontinuity in culture, therefore requiring a revitalization or resurgence. Despite its national and regional importance, however, very little research exists on either of these settler colonial phenomena—cultural continuity and games revival—which underscores Frank’s (2003) observation that traditional Indigenous culture has “never been lost. It’s still right here … All we’ve got to do is uncover it and just start to work” (p. 56). In line with Bamblett’s (2011) observation that the “continuity of culture is a frequent theme in Indigenous writing on sport” (p. 15), both the Indigenous and mainstream articles investigated in this study reflected cultural survival or continuity through a positive lens. Although culture is changing, it is the way in which cultures adapt to change that marks their resiliency. As noted by Heine and Young (1997),

many of the tensions and colliding identities emerging from contemporary versions of Dene games-festivals point not to simple processes of domination and control, but to a recognition in aboriginal communities of the importance of maintaining some level of cultural integrity in the face of changing social conditions and globalizing influences. (p. 369)

Cultural continuity assumes change, and it is within this change that culture stays alive.

Although many of the articles reported on culture from a continuity perspective, two articles from the CBC (Bailey, 2016; Hennig, 2019), in particular, were quick to label the playing of traditional games as revival. The notion of revival stipulates that the culture was absent or lost for a time, and therefore the discourse of keeping the culture alive—which implies a continuous trend—should be nuanced slightly. Both articles use the term comeback within their titles. Hennig’s (2019) article focuses on the “comeback” of hand games in Fort Nelson First Nation, BC, commenting that games are “vital to the survival of [the] nation” (para. 10). Terms, such as “revival,” “resurgence,” or “revitalization,” especially in mainstream media’s reference to Indigenous culture, can reproduce a deficit discourse. This type of “deficit thinking” (Shields et al., 2005), projected within Hennig’s article, is based on assumptions of lost or marginalized cultures. It reproduces the trope of the “vanishing Indian” (Maroukis, 2021), which supposes dying Indigenous cultures, as opposed to changing Indigenous cultures. In terms of cultural continuity, a strength-based approach (Paraschak, 2013; Paraschak & Thompson, 2014) could be used to recognize the ways in which these terms are often actually very positive in Indigenous communities in terms of responding to the material consequences of colonialism. As a result, these terms can be used to highlight Indigenous peoples’ strength and resiliency of culture, as opposed to its marginalization and revival. This deficit discourse is also apparent concerning Indigenous youth and the need to “save” them from a negative future through the SFD framework.

Reclaiming Youth

A second, parallel, discourse in the articles is the notion of reclaiming youth through traditional games and, thus, keeping culture alive. Some of the articles’ interviewees (Laskaris, 2018; Stefanovich, 2018; Two Row Times, 2021) referred to the critical role of traditional games in reclaiming or “saving” Indigenous youth from self-destructive behaviour including suicide (Barker et al., 2017), violence (Ansloos, 2017), substance abuse (Liddell & Burnette, 2017), and disengagement in community life (Islam et al., 2017; Mellor et al., 2020). The suggestion that Indigenous youth can be “reclaimed” through traditional games seems to be in response to the (deficit) discourse that Indigenous youth can expect a negative future. Traditional games are seen, in the articles investigated, to be an ideal site for saving Indigenous youth from an apparently inevitable negative life trajectory. Certainly, some research in SFD suggests there is an evidential basis for such a discourse. In the broader SFD literature, sports are deemed a tool to help “development” in all its forms: social, cultural, economic, youth, etc. Practicing and participating in traditional games, those played for generations, has several benefits. Notably, Dubnewick et al. (2018) suggested that “traditional games can enhance the participation of Indigenous peoples in sport by (a) promoting cultural pride, (b) interacting with Elders, (c) supporting connection to the land, (d) developing personal characteristics, and (e) developing a foundation for movement” (p. 213). For this reason, traditional games have been used in efforts to promote cultural connectedness (Kiran & Knights, 2010; Thompson et al., 2014), inclusion and engagement (Louth & Jamieson-Proctor, 2019), and address social justice (Williams & Pill, 2020) in physical education programs. As can be gleaned from this array of scholarship, and the articles investigated, participation in traditional games augments the relationship between Indigenous youth and their cultures and communities.

The answer to the underlying question of “from what or whom are youth being reclaimed through traditional games?” needs to be framed in a way that broaches broader cultural phenomena. The answer, in short, is from colonialism. The aforementioned risky behaviours, which are often the focus of community, government, and academic intervention efforts, are consequences of colonialism. Certainly, concerns for the material effects of colonialism on Indigenous youth should not be ignored. Nevertheless, the discourses produced about traditional games bringing youth back into their cultures and that such reclamation will have certain effects (i.e., keeping culture alive) that will steer youth off the path of self-destruction seems like a tall order. It is asking much of sports and games to create such drastic cultural and societal changes, especially as it fails to deal with the root issue of colonialism. In this light, SFD programming is rather problematic: sport is not a developmental tool; it is, as Coakley (2011) noted, a “hook” to attract youth into cultural programs, with an objective to “create healthy, productive people; decrease deviance and disruptive actions; and alleviate boredom and alienation” (p. 307). The discourse in question refers to traditional games bringing youth closer to their cultures and communities, which is reminiscent of SFD ideology. The “hook” is the games, and the outcome is community connection. The outcomes of such meaning-making processes may, indeed, be considered developmental, but, as traditional cultural elements, traditional games may also be seen as both the “hook” and the outcome. This stands in contrast to Euro-centric SFD programs whereby the “hook” is disconnected from the outcome.

CONCLUSION

The two primary discourses produced in the 23 Indigenous and mainstream news articles we analyzed—traditional games “keep culture alive” and help “reclaim youth”—both rely on a SFD approach to Indigenous culture and youth; however, traditional games are not often considered within the SFD paradigm—be they a “hook” or the outcome. Indeed, the lack of coverage of traditional games in Canadian media, in general, points to a Western notion of sport and its hegemonic position in the physical cultures and recreational practices of all Canadians. Yet, the Indigenous voices featured in the articles suggest that traditional games may be able to provide an outlet that mainstream sports cannot. In this sense, we must consider the polysemic nature of texts; these articles may have many possible meanings depending on who has access, how Indigenous cultures are portrayed, or audience demographics. Although beyond the scope of this study, a critical media analysis should also consider distribution and accessibility when evaluating the impact of texts. For instance, there is a jarring digital divide when about half of Indigenous households in Canada do not have broadband (Buell, 2021). Who has access to media coverage of traditional games, and how they “read” the texts—either critically or at face-value—is an important follow-up to this current study.

The original intent of this study was to illustrate the divergences in the representations of traditional games in mainstream and Indigenous media; however, in concluding that similar discourses were produced about traditional games, the manner in which the discourses were produced became a focal point for examination. The Western-centric sports journalism approach (Boyle, 2006) to traditional games coverage illuminated a strong SFD ideology within the discourses. As we argued, traditional games have been ignored as an intervention by SFD providers because of the hegemony within the field of Western sport and Western sport models. Therefore, through this discourse analysis, a need to differentiate traditional games from SFD practices for the purposes of cultural and youth development has emerged as a potential direction for future research on Indigenous traditional games. Another area for future research on this topic is the relevance of digital technologies in the changing nature of journalism. The new media landscape provides Indigenous media producers a much-improved opportunity to make Indigenous voices heard, relay their communities’ stories, and influence the representation of Indigenous culture. Although self-determined Indigenous media coverage has, in line with the TRC Calls to Action, promoted Indigenous culture and ways of being, the hegemony of mainstream sport persists in marginalizing traditional games coverage. The lack of visibility of traditional games within both mainstream and Indigenous media has repercussions for how traditional games and Indigenous cultures are understood and SFD is employed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editor for their insightful feedback. This research was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant to the second author.

NOTES

1 “Traditional sporting activities” and “traditional sports” are often used interchangeably with the term “traditional games.”

2 We employ the term “mainstream” media to denote the settler media landscape. Indigenous media is used to distinguish media entities that are owned by and targeted at Indigenous peoples.

3 Windspeaker was established in 1983 as the aforementioned AMMSA and includes a number of regional monthly publications, such as Alberta Sweetgrass, Saskatchewan Sage, Raven’s Eye (published in British Columbia and Yukon), and Ontario Birchbark.

4 Hand games have always involved an element of gambling. Originally, stakes included material possessions, such as materials, tools, and even sled dogs. As of 2005, in an attempt to increase youth participation, the Tłı̨chǫ government introduced big money tournaments, with some cash pots as large as $100,000. Tournament participation has thus increased, drawing participants from throughout Arctic and Subarctic Canada.

5 J. Wilton Littlechild, a Cree lawyer and former Grand Chief of the Treaty 6 First Nation in Alberta, is a two-time Tom Longboat Award Winner, the first Indigenous Albertan to obtain a law degree, and a former Member of Parliament. Littlechild was instrumental in the implementation of the Alberta Indigenous Games (1971), the North American Indigenous Games (1990), and the World Indigenous Games (2015). He has also been inducted into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame and was appointed as a commissioner to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

REFERENCES

Alia, V. (2009). The new media nation: Indigenous peoples and global communication. Bergahn.

Ansloos, J. P. (2017). The medicine of peace: Indigenous youth decolonizing healing and resisting violence. Fernwood.

Bailey, S. (2016, March 10). Ancient Mi’kmaq game of Waltes makes a comeback. CBC News https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/mikmaq-waltes-dice-bowl-game-1.3484894

Bamblett, L. (2011). Straight-line stories: Representations and Indigenous Australian identities in sports discourses. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2, 5-20.

Barker, B., Goodman, A., & DeBeck, K. (2017). Reclaiming Indigenous identities: Culture as strength against suicide among Indigenous youth in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108, e208-e210. https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.108.5754

Beauregard, D., & Paquette, J. (2021). Canadian Cultural Policy in Transition. Routledge.

Bickford, P. (2019, December 3). Five days of training on Hay River Reserve for Dene and Northern Games. NWT News/North. https://www.nnsl.com/hayriverhub/five-days-of-training-on-hay-river-reserve-for-dene-and-northern-games/

Blats, K. (2018, August 13). Intuitiveness, perception key to the game of Lahal. Ha-Shilth-Sa. https://hashilthsa.com/news/2018-08-13/intuitiveness-perception-key-game-lahal

Brady, M. (2005). Creating safe spaces and building social assets for young women in the developing world: A new role for sports. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 33(1/2), 35-49.

Boyle, R. (2006). Sport journalism: Context and issues. SAGE.

Buell, M. (2021, January 18). Indigenous communities must have internet access on their terms. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2021/01/18/indigenous-communities-must-have-internet-access-on-their-terms.html

Burnett, S. (2017, May 25). Gwich’in elder speaks on hand games and destruction of culture. NWT News/North. https://www.nnsl.com/inuvikdrum/gwichin-elder-speaks-on-hand-games/

Bussidor, I., & Bilgen-Reinart, U. (2000). Night spirits: The story of the relocation of the Sayisi Dene. University of Manitoba Press.

CBC News. (2020, August 16). This Hopedale man is writing a manual of traditional games before they’re lost forever. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/traditional-inuit-games-1.5687229

Clark, B. (2014) Framing Canada’s aboriginal peoples: A comparative analysis of Indigenous and Mainstream Television News. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 34(2), 41-64.

Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as “positive development?” Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(3), 306-324. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0193723511417311

Coleby, J., & Giles, A. R. (2013). Discourses at work in media reports on Right To Play’s “Promoting Life-Skills in Aboriginal Youth” program. Journal of Sport for Development, 1(2), 39-52.

Corntassel, J., & Bryce, C. (2012). Practicing sustainable self-determination: Indigenous approaches to cultural restoration and revitalization. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 18(2), 151-162.

Delsahut, F. (2015). From baggataway to lacrosse: An example of the sportization of Native American games. International Journal of the History of Sport, 32(7), 923-938. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2015.1038252

Desmarais, A. (2021, July 31). Meet the Fort Good Hope hand game family dynasty. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/tobac-family-hand-games-1.6113283

Downey, A. (2018). The creator’s game: Lacrosse, identity, and Indigenous nationhood. UBC Press.

Dubnewick, M., Hopper, T., Spence, J.C., & McHugh, T.F. (2018). “There’s a cultural pride through our games”: Enhancing the sport experiences of Indigenous youth in Canada through participation in traditional games. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 42(4), 207-226. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0193723518758456

Edwards, K. (2009). Traditional games of a timeless land: Play cultures in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2, 32-43.

Essa, M., Arellano, A., Stuart, S., & Sheps, S. (2022). Sport for Indigenous resurgence: Toward a critical settler-colonial reflection. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(2), 292-312. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F10126902211005681

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

Ferreira, M. B. R. (2014). Indigenous games: A struggle between past and present. Journal of Sport Science and Physical Education, 67, 48-54.

Fleras, A. (2011). The media Gaze: Representations of diversities in Canada. University of British Columbia Press.

Fleras, A. (2012). Unequal relations: An introduction to race, ethnic, and Aboriginal dynamics in Canada (7th ed.). Pearson.

Forsyth, J. (2007). The Indian Act and the (re)shaping of Canadian Aboriginal sport practices. International Journal of Canadian Studies, 35, 95-111. https://doi.org/10.7202/040765ar

Forsyth, J. (2013). Bodies of meaning: Sports and games at residential schools. In J. Forsyth & A. Giles (Eds.), Aboriginal sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 15-34). UBC Press.

Frank, K. (2003). Vaa tseerii’in, funny Gwich’in stories and games. Arctic Anthropology, 40(2), 56-58. https://doi.org/10.1353/arc.2011.0073

Galipeau, M., & Giles, A. R. (2014). An examination of cross-cultural mentorship in Alberta’s Future Leaders Program. In K. Young & C. Okada (Eds.), Research in the sociology of sport (pp, 147-170). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1476-285420140000008007

Gardam, K., & Giles, A. R. (2016). Media representations of policies concerning education access and their roles in seven First Nations students’ deaths in northern Ontario. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2016.7.1.1

Gartner-Manzon, S., & Giles, A. R. (2016). A case study of the lasting impacts of employment in a development through sport, recreation, and the arts program for Aboriginal youth. Sport in Society, 19(2), 159-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1067770

Gartner-Manzon, S., & Giles, A. R. (2018). Lasting impacts of an Aboriginal youth leadership retreat? A case study of Alberta’s Future Leaders Program. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(4), 338-352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1470937

Giles, A. R. (2004). Kevlar®, Crisco®, and menstruation: “Tradition” and Dene games. Sociology of Sport Journal, 21(1), 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.21.1.18

Giles, A. R. (2005a). The acculturation matrix and the politics of difference: Women and Dene games. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 25(1), 355-372.

Giles, A. R. (2005b). A Foucaultian approach to menstrual practices in the Dehcho region, Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic Anthropology, 42(2), 9-21. https://doi.org/10.1353/arc.2011.0094

Giles, A. R. (2008). Beyond “add women and stir”: Politics, feminist development, and Dene games. Leisure/Loisir, 32(2), 489-512. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2008.9651419

Ginsburg, F. (1991). Indigenous media: Faustian contract or global village? Cultural Anthropology, 6(1), 92-112. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1991.6.1.02a00040

Government of Canada. (2020). Application guidelines—Sport for social development in Indigenous communities. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/funding/sport-support/social-development-indigenous-communities/application-guidelines.html#a3

Government of Canada. (2021). Federal budget. https://www.budget.canada.ca/2021/report-rapport/p3-en.html#chap8

Gregoire, L. (2016, February 22). Nunavut students promote healthy living through Inuit games. Nunatsiaq News. https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/65674nunavut_students_promote_healthy_living_through_inuit_games/

Guttmann, A. (1978). From ritual to record: The nature of modern sports. Columbia University Press.

Halas, J. (2013). R. Tait McKenzie Scholar’s Address: Physical and health education as a transformative pathway to truth and reconciliation with aboriginal peoples. Physical & Health Education Journal, 79(3), 41-49.

Hall, T. D., & Fenelon, J. V. (2009). Indigenous peoples and globalization: Resistance and revitalization. Routledge.

Handler, R., & Linnekin, J. (1984). Tradition, genuine or spurious. Journal of American Folklore, 97(385), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.2307/540610

Hanusch, F. (2013). Charting a theoretical framework for examining Indigenous journalism culture. Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture & Policy, 149, 82-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1314900110

Harding, R. (2005). The media, Aboriginal people and common sense. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 25(1), 311-335.

Harding, R. (2006). Historical representations of aboriginal people in the Canadian news media. Discourse & Society, 17(2), 205-235. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0957926506058059

Hayhurst, L. M. C., & Giles, A. (2013). Private and moral authority, self-determination, and the domestic transfer objective: Foundations for understanding sport for development and peace in Aboriginal communities in Canada. Sociology for Sport Journal 30(4), 504-519. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.30.4.504

Heine, M. K. (2006). Dene games: An instruction and resource manual. Sport North Foundation.

Heine, M. K. (2014). No “museum piece”: Aboriginal games and cultural contestation in subarctic Canada. In C. Hallinan & B. Judd (Eds.), Native games: Indigenous peoples and sports in the post-colonial world (pp, 1-19). Emerald.

Heine, M. K., & Young, K. (1997). Colliding identities in Arctic Canadian sports and games. Sociological Focus, 30(4), 357-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.1997.10571086

Hennig, C. (2019, April 6). ‘Our culture is going to survive’: Traditional Indigenous hand games make a comeback in northern B.C. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/hand-games-fort-nelson-1.5085273

Henriques, J., Holloway, W., Urwin, C., Venn, C., & Walkerdine, V. (1984). Changing the subject. Routledge.

Islam, D., Zurba, M., Rogalski, A., & Berkes, F. (2017). Engaging Indigenous youth to revitalize Cree culture through participatory education. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 11(3), 124-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2016.1216833

Jeppesen, S. (2021). Transformative media: Intersectional technopolitics from Indymedia to #BlackLivesMatter. University of British Columbia Press.

Jewell, E., & Moseby, I. (2021). Calls to action accountability: A 2021 status update on reconciliation. Yellowhead Institute.

Kataquapit, X. (2018, August 20). Traditional teachings a feature of Wabun Youth Gathering. Windspeaker. https://windspeaker.com/news/windspeaker-news/traditional-teachings-a-feature-of-wabun-youth-gathering

Kiran, A., & Knights, J. (2010). Traditional Indigenous games promoting physical activity and cultural connectedness in primary schools—Cluster randomised control trial. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 21(2), 149-151. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE10149

Laskaris, S. (2018, June 7). Indigenous-themed games for Indigenous youth held in northern Alberta. Windspeaker. https://windspeaker.com/news/sports/indigenous-themed-games-for-indigenous-youth-held-in-northern-alberta

Lavallée, L., & Lévesque, L. (2013). Two-eyed seeing: Physical activity, sport, and recreation promotion in Indigenous communities. In J. Forsyth & A. R. Giles (Eds.), Aboriginal peoples and sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 206-228). UBC Press.

Liddell, J., & Burnette, C. E. (2017). Culturally-informed interventions for substance abuse among Indigenous youth in the United States: A review. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 14(5), 329-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1335631

Louth, S., & Jamieson-Proctor, R. (2019). Inclusion and engagement through traditional Indigenous games: Enhancing physical self-efficacy. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(12), 1248-1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1444799

Love, T., & Tilley, E. (2013). Temporal discourse and the news media representation of Indigenous–non-Indigenous relations: A case study from Aotearoa New Zealand. Media International Australia, 149(1), 174-188. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1329878X1314900118

Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2021). Indigenous environmental media coverage in Canada and the United States: A comparative critical discourse analysis. The Journal of Environmental Education, 52(2), 83-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2020.1852525

MacDonald, C., & Steenbeek, A. (2015). The impact of colonization and Western assimilation on wealth and wellbeing of Canadian aboriginal people. International Journal of Regional and Local History, 10(1), 32-46. https://doi.org/10.1179/2051453015Z.00000000023

Mackey, E. (1998). Becoming Indigenous: Land, belonging, and the appropriation of aboriginality in Canadian nationalist narratives. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Anthropology, 42(2), 150-178.

Maroukis, T. C. (2021). We are not a vanishing people: The Society of American Indians, 1911-1923. University of Arizona Press.

McCarthy, J. (2018, March 13). Weledeh roars to the top at Traditional Games. NWT News/North. https://www.nnsl.com/nwtnewsnorth/weledeh-roars-to-the-top-at-traditional-games/

McKay, S. (2018, February 15). Youth show skills at 2018 Dene Games Summit in Inuvik. NWT News/North. https://www.nnsl.com/inuvikdrum/youth-show-skills-2018-dene-games-summit-inuvik/

Mellor, A., Surrounded by Cedar Child and Family Services, Cloutier, D., & Claxton, N. (2020). “Youth will feel honoured if they are reminded they are loved”: Supporting coming of age for urban Indigenous youth in care. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 16(2), 308-321. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i1.33179

Miller, J. R. (1997). Shingwauk’s vision: A history of Native residential schools. University of Toronto Press.

Milloy, J. S. (1999). A national crime: The Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986. University of Manitoba Press.

Morritt-Jacobs, C. (2020, March 17). Strengthening unity of the Dene Nation through hand games. Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/strengthening-unity-of-the-dene-nation-through-hand-games/

Morrow, D. (1992). The institutionalization of sport: A case study of Canadian lacrosse, 1844–1914. International Journal of the History of Sport, 9(2), 236-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523369208713792

Mrozek, D. (1987). Games and sports in the Arctic. Journal of the West, 26(1), 34-46.

Nagengast, C. (1997). Women, minorities, and Indigenous peoples: Universalism and cultural relativity. Journal of Anthropological Research, 53(3), 349-369. https://doi.org/10.1086/jar.53.3.3630958

Narine, S. (2013). Littlechild pushes for recognition of Indigenous games in sports halls of fames. Alberta Sweetgrass, 20(10). https://ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/littlechild-pushes-recognition-indigenous-games-sports-halls-fames

Nemec, S. (2021). Can an indigenous media model enrol wider non-Indigenous audiences in alternative perspectives to the ‘mainstream.’ Ethnicities, 21(6), 997-1025. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211029807

News Media Canada. (2020). Snapshot 2020 report: A look at Canada’s Newspaper Industry. https://nmc-mic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Snapshot-2020_REPORT_Total-Industry_2020.09.23.pdf

Nicholls, S., Giles, A. R., & Sethna, C. (2011). Perpetuating the ‘lack of evidence’ discourse in sport for development: Privileged voices, unheard stories and subjugated knowledge. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(3), 249-264. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1012690210378273

Nolen, S. (2019, January 16). The decolonization game: An ancient sport puts Mexicans in touch with their Indigenous past. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-the-decolonization-game-an-ancient-sport-puts-mexicans-in-touch-with/

Paraschak, V. (1998). “Reasonable amusements”: Connecting the strands of physical culture in Native lives. Sport History Review, 29(1), 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1123/shr.29.1.121

Paraschak, V. (2013). Hope and strength(s) through physical activity for Canada’s Aboriginal peoples. In C. Hallinan & B. Judd (Eds.), Native games: Indigenous peoples and sports in the post-colonial world (pp. 229-246). Emerald.

Paraschak, V., & Thompson, K. (2014). Finding strength(s): Insights on Canadian Aboriginal physical cultural practices. Sport in Society, 17(8), 1046-1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.838353

Parker, I. (1992). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology. Routledge.

Parlebas, P. (2020). The universals of games and sports. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 593877. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.593877

Pegley, K. (2004). Waiting for our miracle: Gender, race and nationhood in Canada for Asia. Canadian Journal for Traditional Music, 31, 1-9.

Prins, H. E. L. (2002). Visual media and the primitivist perplex: Colonial fantasies, Indigenous imagination, and advocacy in North America. In F. D. Ginsburg, L. Abu-Lughod, & B. Larkin (Eds.), Media worlds: Anthropology on new terrain (pp. 58-74). University of California Press.

Rice, B. (2019). Beyond competition: An Indigenous perspective on organized sport. Journal of Sport History, 46(2), 166-174. https://doi.org/10.5406/jsporthistory.46.2.0166

Ritchot, M. (2021, April 26). Coral Harbour school showcases traditional Inuit games. Nunatsiaq News. https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/coral-harbour-school-showcases-traditional-inuit-games/

Robillard, B. (2019). Playing with a great heart: Restoring the original intent of play through Indigenous games and activities. Manitoba Aboriginal Sports and Recreation Council.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996). Bridging the cultural divide: A report on Aboriginal people and criminal justice in Canada. Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. https://data2.archives.ca/rcap/pdf/rcap-464.pdf

Rutgers, J.-S. (2021, August 16). Landing young leaders. Winnipeg Free Press. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/landing-young-leaders-575103812.html

Schnitzer, M., Stephenson Jr, M., Zanotti, L., & Stivachtis, Y. (2013). Theorizing the role of sport for development and peacebuilding. Sport in Society, 16(5), 595-610. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.690410

Schulenkorf, N., Thomson, A., & Schlenker, K. (2011). Intercommunity sport events: Vehicles and catalysts for social capital in divided societies. Event Management, 15(2), 105-119. http://dx.doi.org/10.3727/152599511X13082349958316

Scott, J., & Fletcher, A. (2014). In conversation: Indigenous cultural revitalization and ongoing journeys of reconciliation. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 34(2), 223-237.

Shields, C., Bishops, R., & Mazawi, A. E. (2005). Pathologising practices: The impact of deficit thinking on education. Peter Lang.

Short, D. (2018, December 11). Simpson students take on traditional games. NWT News/North. https://www.nnsl.com/sports/simpson-students-take-on-traditional-games/

Smith, A. (2016, May 25). Hunters’ endurance, strength and agility boosted by games. Windspeaker. https://www.windspeaker.com/news/sports/hunters-endurance-strength-and-agility-boosted-by-games