Amanda McKinnon1, Rebecca L. Bassett-Gunter1, Jessica Fraser-Thomas1, & Kelly P. Arbour-Nicitopoulos2

1 York University, Canada

2 University of Toronto, Canada

Citation:

McKinnon, A., Bassett-Gunter, R.L., Fraser-Thomas, J., & Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P. (2022). Understanding sport as a vehicle to promote positive development among youth with physical disabilities. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Research has explored the benefits and challenges associated with sport participation among youth with physical disabilities (YWPD), however few studies have attempted to understand how sport may facilitate or hinder positive development. Positive youth development (PYD) is a widely used approach to understand youth development through sport, however limited research exists among YWPD. To address this gap, the study adopted Holt and colleagues’ (2017) model of PYD through sport to (a) uncover YWPD’s perspectives on the developmental outcomes associated with organized sport participation and (b) understand perceived social-contextual factors influencing these outcomes. Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted among YWPD (N = 9; age between 14-21; seven male participants, two female participants). Outcomes discussed were mostly positive, though some participants reported negative outcomes. Participants experienced positive physical, social, and personal outcomes including the development of life skills. Positive outcomes were largely influenced by a sport climate that was supportive and encouraging, facilitated personal growth and athletic development, and promoted a sense of community and connectedness. These findings further our understanding of the utility of organized sport as a context to promote PYD among YWPD, and suggest that fostering experiences of mastery, belonging, challenge, and autonomy may be critically important.

UNDERSTANDING SPORT AS A VEHICLE TO PROMOTE POSITIVE DEVELOPMENT AMONG YOUTH WITH PHYSICAL DISABILITIES

Sport Participation among Youth with Physical Disabilities

Sport offers a rich context for youth with physical disabilities (YWPD) to gain many physical, social, and psychological health benefits (Martin, 2011; McLoughlin et al., 2017; Murphy & Carbone, 2008; Shapiro & Martin, 2010, 2014; te Velde et al., 2018; Turnnidge et al., 2012). Despite tremendous improvements in sport opportunities following acts such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (Cottingham et al., 2016), YWPD continue to face unique barriers that may limit their participation in sport, the quality of their sport experiences, and the likelihood of favourable outcomes (Bantjes et al., 2015; Jaarsma et al., 2015; McLoughlin et al., 2017; Orr et al., 2018). Factors that have been shown to hinder sport participation and positive sport experiences among YWPD include social isolation and bullying, exclusion, inaccessible premises, and lack of sports aids and adapted activities (Bantjes et al., 2015; Jaarsma et al., 2015; Orr et al., 2018). Negative sport experiences can ultimately jeopardize current and future sport participation among YWPD (Orr et al., 2018). As such, it is critical to foster positive sport experiences to increase the likelihood that YWPD remain engaged in sport and, thus, enjoy the benefits.

The social environment plays an integral role in facilitating positive sport experiences for people with disabilities (Evans et al., 2018; Martin Ginis et al., 2016; Martin & Mushett, 1996; Orr et al., 2018; Shirazipour et al., 2018; Turnnidge et al., 2012). Research focused on understanding optimal parasport participation experiences (e.g., Quality Parasport Participation [QP] Framework; Evans et al., 2018) suggests that parents, peers, and coaches foster the following key elements that make up positive sport experiences among persons with disabilities: mastery (i.e., a sense of competence and accomplishment), challenge (i.e., feeling appropriately tested), belonging (i.e., feeling part of a group or accepted by others), autonomy (i.e., having independence, choice or control), meaning (i.e., working toward a valued goal or having a sense of responsibility to oneself or others) and engagement (i.e., feeling involved, motivated, and focused). For example, sport environments that offer opportunities for peer engagement (i.e., group-based programming), with knowledgeable leaders (Shirazipour et al., 2018) and coaches who are professional, collaborative, and considerate (Allan et al., 2020) have shaped the most positive sport experiences for people with disabilities. Indeed, emerging research guided by the QP framework (Evans et al., 2018) has begun to inform our understanding of factors that may foster quality sport experiences, while other work continues to examine the potential benefits and challenges associated with sport participation among YWPD (Murphy & Carbone, 2008; Shields & Synnot, 2016). However, there has been a call for research to gain a broader understanding of the outcomes associated with sport participation among YWPD (Bragg & Pritchard-Wiart, 2019), as well as the processes through which these outcomes are acquired (Turnnidge et al., 2012).

Positive Youth Development Through Sport

Positive youth development (PYD) is an approach that may be helpful in enhancing our understanding of outcomes and processes related to sport participation among YWPD. PYD is a strength-based approach (Roth et al., 1998) that may be especially valuable in exploring sport participation among YWPD, because it challenges the traditionally dominant construct of disability whereby disability is problematized and persons with disabilities are viewed as objects for intervention (e.g., medical model; Townsend et al., 2015). Instead, through the lens of PYD, sport may be conceptualized as a context through which the unique strengths and abilities of YWPD are harnessed, celebrated, and developed.

The PYD approach has been used widely to understand the developmental outcomes associated with sport participation among youth without disabilities (Fraser-Thomas & Côté, 2009; Fraser-Thomas et al., 2005; Holt & Neely, 2011), as well as the processes through which these outcomes are acquired (Holt et al., 2017; Petitpas et al., 2005). Holt and colleagues’ (2017) model of PYD through sport suggests that organized sport participation can lead to the acquisition of positive personal (e.g., positive self-perceptions, perseverance, hard work), social (e.g., independence, leadership, and teamwork skills), and physical outcomes (e.g., fundamental movement skills). The model (i.e., PYD through sport model hereafter) suggests that a positive youth development climate (PYD climate) and a life skills program focus are important factors that, together, may optimize PYD through sport (Holt et al., 2017).

A PYD climate refers to the social-contextual factors (i.e., features of the social environment of sport) that enable youth to gain experiences that promote PYD outcomes (Holt et al., 2017). The PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) posits that positive adult (e.g., coach) and peer relationships, along with the supportive involvement of parents, can create a positive social environment that is conducive to developing PYD outcomes. A life skills program focus means that activities and techniques are deliberately integrated within the sport curriculum to develop life skills (e.g., establishing high expectations and accountability for behavior, role-modeling desired behaviour, team building activities, and peer mentoring) and transfer activities (e.g., discussions regarding how skills learned through sport can transfer to other contexts; Holt et al., 2017). Sport environments that foster a favourable PYD climate and provide a life skills program focus can promote personal, social, and physical PYD outcomes (Holt et al., 2017). The model also acknowledges the possibility for implicit learning; whereby PYD outcomes can be achieved without a life skills program focus, so long as a PYD climate is fostered (Holt et al., 2017).

Positive Youth Development through Sport for Youth with Disabilities

Although the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) is not specific to a disability sport context, it considers elements that are relevant to athletes with disabilities. For instance, the concept of PYD climate applies to YWPD, as they may rely heavily on social agents (e.g., parents, peers, and coaches) to facilitate positive sport experiences (Lower-Hoppe et al., 2021; Martin & Whalen, 2014; Shirazipour et al., 2018; Volfson et al., 2020). Furthermore, compared to youth without disabilities, YWPD may face more challenges and have fewer opportunities to develop and practice critical life skills (Kingsnorth et al., 2007). As such, the focus on understanding how sport participation may facilitate life skill development, as well as the acquisition of personal, social, and physical outcomes, may be particularly relevant and beneficial to explore among YWPD.

METHODS

Sampling and Recruitment Methods

All procedures were approved by the research ethics board at the first author’s institution. A maximum variation purposive sampling method was used to recruit YWPD from across Ontario, Canada (February 2019 – March 2020) via previous research participant pools (N = 2), partnerships with community organizations (N = 5), and snowball sampling (N = 2). The eligibility criteria included youth: (a) between the ages of 14-21, (b) who self-identified as having a physical disability, (c) who were participating in at least one organized sport program, (d) whose impairment(s) did not prevent oral communication or their capacity to provide informed consent, and (e) who spoke English. Participants up to the age of 21 years were included to reflect the age at which youth with disabilities transition from child to adult services (including sport programming) within Ontario, Canada (Leo et al., 2018). Sport was defined as any organized and adult supervised, competitive, or recreational sport activity (Holt et al., 2017) taking place outside of regular school hours (i.e., not physical education class).

Participants

Nine YWPD (mean age: 16.4 ± 2.3 years; seven males; two females) agreed to participate and met eligibility criteria. The sample represented nine different sports programs across varying levels of competition, including recreational and competitive at the local, provincial, and national level. Table 1 details demographic and sport information. Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from all participants. If a participant was under the age of 16, participant assent and informed consent from a parent were obtained. Participation was voluntary, and participants received a $25 honorarium.

Table 1 – Participant Demographics and Sport Information

a Recreational: non-competitive or for fun.

b Competitive: some element of competition (e.g., competing in meets, competitions, tournaments).

c Provincial: competing for Team Ontario.

d National: competing for Team Canada.

e Adapted: adaptations or accommodations, participate or compete among athletes with disabilities.

f Integrated: adaptions or accommodations, participate or compete among athletes with and without disabilities.

g Mainstream: no adaptations or accommodations, participate or compete among athletes without disabilities

Theoretical Framework and Methodological Approach

The PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) provided a theoretical framework to guide the project through informing the research question, the development of the interview guide, and the data analysis process. The study adopted a relativist ontology and a transactional subjectivist epistemology. Accordingly, data collection and analysis were approached with the assumption that multiple realities exist. In other words, the phenomenon may be interpreted differently based on individuals’ perceptions, which are socially and experientially constructed, and knowledge is co-constructed through interactions between the researcher and participants (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). These assumptions were acknowledged within the study design. The section below outlines steps that were taken to ensure findings were interpreted and presented in a way that best reflected participants’ experiences (Nowell et al., 2017).

Data Collection

Participants completed a short online questionnaire (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, California, USA), where informed consent, demographic (e.g., age, sex, nature of their disability), and sport (e.g., type of sport, frequency of participation, and level of competition) information were collected. Participants were then instructed to create a concept map, which prompted them to recall, and write-down key thoughts, feelings, and experiences related to their sport. The concept maps were not used as a form of data analysis, but rather encouraged participants to reflect on their sport experiences and served as a memory aid to facilitate discussions during the in-depth interview (Bagnoli, 2009). The concept map was submitted electronically and reviewed by the first author prior to the interview.

Participants chose a preferred method (i.e., telephone [n = 5] or video [n = 4]) to complete a semi-structured interview, guided by 10 open-ended questions. The interviews lasted 40-60 minutes each (M = 48). The first question, which referred to participants’ concept map, was intended to build rapport and gain a deeper understanding of the concept map (e.g., Can you walk me through the different things you included in your concept map? Why did you choose to include these things?). Subsequent questions were guided by the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) and expanded on participants’ significant positive and negative moments in sport, whether they had learned or gained anything from their experiences, as well as the social-contextual factors that affected their experiences. To remain consistent with the guiding model, the social-contextual factors under investigation included adult- (i.e., coach and instructor) and peer-relationships, and parent or family involvement. All interviews were conducted by the first author who does not have a physical disability but participated in sport, both at the recreational and competitive level, for twelve years as a child and adolescent. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Three participants chose to have a parent present during the interview; however, parents were encouraged to allow participants to speak for themselves.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was guided by an amended version of Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step methodology for thematic analysis (Nowell et al., 2017), which outlines strategies to establish trustworthiness (e.g., credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability; Lincoln & Guba, 1985) throughout each phase of data analysis (Nowell et al., 2017). This approach also aligns with Braun and Clarke’s most recent work, which emphasizes the iterative, reflexive, deliberate, and organic (i.e., non-linear) process that underpins thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019; Braun et al., 2016). Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and manually coded by the first author. Interview transcripts were compared with original audio-recordings to ensure accuracy of transcription (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We invited participants to engage in the process of member-reflection in an effort to further promote the co-construction of knowledge. Accordingly, prior to commencing the thematic analysis, participants were given the opportunity to review their transcripts and take part in any further discussion; eight participants responded and noted that they did not have anything further to share or contribute at that time.

During phase one of data analysis (data familiarization), the first author read through the dataset twice, while actively searching for meaning and patterns. A reflexive journal was kept to document the researchers’ reflective thoughts related to a) the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017), b) their own lived experiences, and c) initial ideas for coding (Braun & Clarke, 2019; Nowell et al., 2017). During phase two (generating initial codes), initial codes were deductively generated using concepts related to PYD climate (e.g., peer, parent, and coach relationships), PYD outcomes (e.g., personal, social, and physical), and a life skill program focus (e.g., life skill building and transfer activities; Holt et al., 2017). Given the exploratory nature of the study, the dataset was coded a second time using an inductive approach (Braun et al., 2016), to identify salient codes that may not have been directly related to the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017). Reflexive journaling was performed and a coding manual was kept to organize codes, descriptions, and data extracts (Braun & Clarke, 2019; Saldaña, 2015). It was through the inductive coding process that the authors recognized themes related to the QP framework, and as such subsequently considered these themes while interpreting the data. During phase three (searching for themes), codes were grouped and sorted into overarching themes and subthemes (Nowell et al., 2017). During phases four (reviewing themes) and five (defining and naming themes), the name, definition, and content of each theme and subtheme was reviewed and discussed with three experts (i.e., co-authors) in the field of PYD, youth sport, and disability research. As part of phase six (producing the report), we once again invited participants to engage in the process of member reflection; we shared the report of the findings with all participants via email, prompting them for any further reflections or feedback. Six participants replied and suggested that the report of the findings was representative of their experiences, sharing no further insights. Although the participants did not provide any further insight, the opportunity to engage in member reflection was an important part of the study protocol because it allowed participants to see their thoughts (transcripts) and the interpretations of the researchers (findings). This process offered YWPD the opportunity to confirm whether the findings resonated with their experiences and perspectives, as well as encouraged them to share alternate interpretations and additional insights (Smith & McGannon, 2018).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

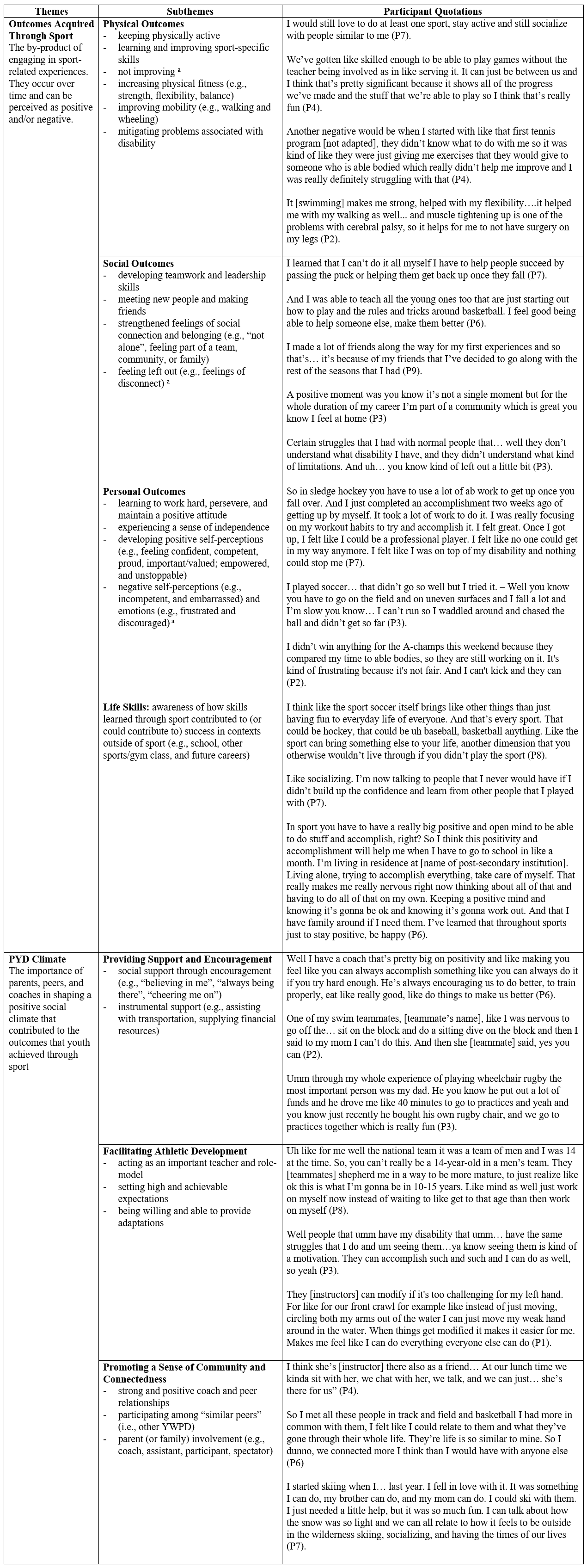

Two overarching themes were identified with various subthemes. Table 2 provides a summary of the themes and subthemes, and sample participant quotations. The following sections present and discuss the study findings within the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) while drawing on relevant sport and disability research. The theoretical and pragmatic implications of these findings, as well as future research directions are also considered.

Table 2 – Themes and Subthemes with Descriptions and Participant Quotations

a Outcomes perceived as negative.

Theme One: Outcomes Acquired Through Sport

Theme one highlights the outcomes that YWPD reported from engaging in sport-related experiences. Outcomes were categorized into the following four subthemes, which were identified deductively based on elements from the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017): a) physical outcomes, b) social outcomes, c) personal outcomes, and d) life skills. Although most of these outcomes were perceived to be positive, it is important to reflect on the negative outcomes that were also disclosed.

Physical Outcomes

YWPD reported that playing sport provided them with opportunities—and in some cases, a reason—to be physically active. Every single participant expressed a desire to continue playing sport or being physically active in the future: “I would still love to do at least one sport, stay active and still socialize with people similar to me” (P7, M, Age 15, Adapted Skiing and Sledge Hockey). This outcome is consistent with the PYD through sport model (Skills for Healthy Active Living, Holt et al., 2017), and supports the notion that sport participation may promote increased physical activity participation among YWPD (Buffart et al., 2008; Marques et al., 2016). Given that physical activity rates among YWPD remain low (Murphy & Carbone, 2008; Woodmansee et al., 2016), this finding highlights the need to leverage organized sport opportunities to promote long-term physical activity participation.

YWPD reported experiencing improvements in strength, balance, and flexibility, which, in some cases, helped improve mobility (walking and wheeling) and mitigate disability-related health problems:

It [swimming] makes me strong, helped with my flexibility. It helped me with my walking as well… and muscle tightening up is one of the problems with cerebral palsy, so it helps for me to not have surgery on my legs (P2, F, Age 14, Swimming).

These findings indicate how participants believed that organized sport participation yielded physical benefits that may have important implications related to improving or maintaining their functional ability and physical independence (e.g., perform activities of daily living; Murphy & Carbone, 2008; Rimmer, 2001; te Velde et al., 2018). This is consistent with previous research highlighting the importance of physical health considerations as motivation for sport participation among some athletes with disabilities (Molik et al., 2010).

Finally, YWPD discussed opportunities to learn and develop a wide range of physical skills related to their sport (e.g., swim strokes) and emphasized the importance of seeing themselves “get better”. For example,

We’ve gotten like skilled enough to be able to play games without the teacher being involved as in like serving it. It can just be between us and I think that’s pretty significant because it shows all of the progress we’ve made and the stuff that we’re able to play so I think that’s really fun (P4, M, Age 15, Wheelchair Tennis and Adapted Skiing).

YWPD were able to recognize and appreciate the benefits of physical outcomes and being challenged. In fact, participants felt that a lack of improvement or feeling held back in their athletic development was a negative outcome of their sport experiences. YWPD have previously articulated the need to make progress, feel challenged, and achieve mastery within sport (Bantjes et al., 2015). Sport environments that offer opportunities for YWPD to experience challenge and mastery may be particularly valuable (Evans et al., 2018) and subsequently facilitate meaningful PYD outcomes.

Social Outcomes

According to YWPD, the social environment played a role in facilitating several positive outcomes, including making friends, as well as developing teamwork and leadership skills. For example, YWPD discussed being a team player, collaborating with peers, showing respect, and teaching and helping others. Some participants even expressed a desire to be a role-model for others and to educate people about disability and parasport.

As a 21-year-old like I feel like I could help people show them like, “ok this is what CP [cerebral palsy] looks like, this is what I can tell you about it, and there’s people like me in this world that you just have to look out for” (P8, M, Age 21, Soccer).

The social outcomes reported by YWPD resonate with those outlined in the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017). Sport-based PYD literature among youth with (e.g., Turnnidge et al., 2012) and without disabilities (Lower-Hoppe et al., 2021) document the value of relationships and social interactions in promoting outcomes related to teamwork and leadership skills, as was found in this study.

Participants valued the connections and relationships they developed through sport, which were thought to promote feelings of belonging and acceptance. This was evident when YWPD spoke about being part of a community, team, or family: “A positive moment was you know it’s not a single moment but for the whole duration of my career I’m part of a community which is great you know I feel at home” (P3, M, Age 16, Wheelchair Rugby). This finding is consistent with previous research identifying belongingness as an outcome associated with sport participation among YWPD (Turnnidge et al., 2012), as well as an important component in fostering positive sport experiences among athletes with disabilities (Evans et al., 2018).

In contrast, some YWPD expressed feeling disconnected or excluded when they experienced difficulties relating to peers or participating in sport. These outcomes were perceived negatively and reported mainly by YWPD who had participated in integrated sport settings (e.g., among peers without disabilities or with varying levels of abilities). One YWPD highlighted, “Certain struggles that I had with normal people that… well they don’t understand what disability I have, and they didn’t understand what kind of limitations. And uh… you know kind of left out a little bit” (P3, M, Age 16, Wheelchair Rugby).

Although integrated sport settings can benefit both athletes with and without disabilities (Klenk et al., 2019), participating among peers with large differences in abilities may thwart feelings of competence and belonging among YWPD (Shirazipour et al., 2018) and contribute to negative sport experiences (Orr et al., 2018). The present findings underscore the importance of providing YWPD with opportunities to engage in positive interpersonal interactions through sport, and suggest that experiencing a sense of competence, relatedness, and acceptance could support the development of positive social outcomes.

Personal Outcomes

YWPD believed that sport provided them with opportunities to work towards achieving a goal, overcoming a challenging task (e.g., learning a new skill), and coping with difficult or unpleasant situations (e.g., tough loss, failed attempt, injury). From these experiences, YWPD spoke about learning to work hard, push themselves, persevere, and stay positive. For example,

And for track and field, like never give up almost? Is one of the things I’ve learned. Because sometimes it can be next to impossible to complete or accomplish but really if you practice every day, every week you’ll eventually get there. I didn’t think I’d be able to throw past five meters for shot put but now I’m throwing like seven meters like it’s not impossible you just have to work really hard towards it (P6, F, Age 17, Wheelchair Basketball and Track & Field – Throwing).

These findings reinforce the notion that when YWPD feel adequately challenged in their sport (i.e., perceive that activities require their best effort, test their limits and push them beyond their comfort zone), they are more likely to have quality experiences (Evans et al., 2018) that may, in turn, promote positive outcomes (Turnnidge et al., 2012).

YWPD reported a greater sense of physical independence from playing sport (e.g., feeling free from constraints and having control over their body and experiences) because it provided them with opportunities to exert their autonomy: “It [skiing] let’s me go down the hill at my own pace, at my own speed in my own area” (P5, M, Age 14, Sledge Hockey and Adapted Skiing). Independence is an outcome that has been previously identified by researchers examining sport participation among youth with (Turnnidge et al., 2012) and without disabilities (Holt et al., 2017).

Participants described favourable outcomes associated with experiencing mastery (e.g., accomplishing a goal, learning a skill, and winning), such as feeling confident, proud, empowered, and competent. These feelings seemed to be reinforced when YWPD completed these achievements independently (i.e., without needing assistance from others or support from assistive devices supported these feelings). For example,

So, in sledge hockey you have to use a lot of ab work to get up once you fall over. And I just completed an accomplishment two weeks ago of getting up by myself. It took a lot of work to do it. I was really focusing on my workout habits to try and accomplish it. I felt great. Once I got up, I felt like I could be a professional player. I felt like no one could get in my way anymore. I felt like I was on top of my disability, and nothing could stop me (P7, M, Age 15, Sledge Hockey and Adapted Skiing).

These findings suggest that participating in organized sport may offer valuable experiences through which YWPD can develop positive self-perceptions and experience a sense of independence, and competence (te Velde et al., 2018; Turnnidge et al., 2012). However, YWPD indicated that experiences which limited their ability to improve or successfully participate and compete contributed to negative self-perceptions (e.g., embarrassment and incompetence) and emotions (e.g., frustration and discouragement): “I didn’t win anything for the A-champs this weekend because they compared my time to able bodies, so they are still working on it. It’s kind of frustrating because it’s not fair. And I can’t kick, and they can” (P2, F, Age 14, Swimming). Similar experiences have been shown to hinder sport participation and thwart perceptions of autonomy and competence among YWPD (Orr et al., 2018).

Overall, the positive outcomes discussed are consistent with the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) and seem to highlight the importance of enabling YWPD to feel appropriately challenged, successful, and autonomous within sport (Evans et al., 2018; Shirazipour et al., 2018) as a potential strategy for promoting PYD outcomes.

Life Skills

The previous sections illustrate that playing sport provided YWPD with many opportunities to develop and practice important skills within sport. Importantly, all participants recognized that the skills they learned through sport had helped (or could help) them succeed in different areas outside of sport (e.g., school, personal life, other sports and physical education class, and future careers). For example, one participant credited his ability to interact and socialize with others, to learning from his teammates and building his confidence through sport: “I’m now talking to people that I never would have if I didn’t build up the confidence and learn from other people that I played with” (P7, M, Age 15, Sledge Hockey and Adapted Skiing). Another participant made the connection between learning to be positive and open-minded in sport, and how it would help her in her transition to post-secondary education:

In sport you have to have a really big positive and open mind to be able to do stuff and accomplish, right? So, I think this positivity and accomplishment will help me when I have to go to school in like a month. I’m living in residence at [name of post-secondary institution]. Living alone, trying to accomplish everything, take care of myself. That really makes me really nervous right now thinking about all of that and having to do all of that on my own. Keeping a positive mind and knowing it’s gonna be ok and knowing it’s gonna work out. And that I have family around if I need them. I’ve learned that throughout sports just to stay positive, be happy (P6, F, Age 17, Wheelchair Basketball and Track & Field – Throwing).

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Turnnidge et al., 2012), these findings demonstrate a link between sport participation and life skill development among YWPD and highlight the importance of social factors within the sport context (Holt et al., 2017; Lower-Hoppe et al., 2021). Life skills are conceptualized as ‘internal personal assets, characteristics, and skills such as goal setting, emotional control, self-esteem, and hard work ethic that can be facilitated or developed in sport and transferred for use in non-sport settings’ (Gould & Carson, 2008, p. 60). This finding adds to existing disability sport research by providing evidence that organized sport participation may facilitate life skill transfer among YWPD, which is an essential component of life skill development (Pierce et al., 2017). However, YWPD did not elaborate on how they learned to make these connections, suggesting that life skill transfer may have occurred implicitly (e.g., in the absence of life skill transfer activities; Holt et al., 2017). It is possible that participants may have been unaware of specific strategies utilized by their coaches to teach life skill transfer (e.g., discussions or debriefs regarding how skills learned through sport can transfer to other contexts; Holt et al., 2017). As such, explicit learning should not be ruled out and should be further explored. Future research should examine the perspectives of YWPD and their coaches to further an understanding of how life skill development and transfer are facilitated through sport.

In sum, YWPD highlighted positive outcomes that aligned with the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017). Our findings extend previous research among YWPD (Turnnidge et al., 2012) by suggesting that organized sport has the potential to facilitate life skill transfer, as well as contribute to unfavourable outcomes among YWPD (i.e., negative emotions, negative self-perceptions and feeling left out). In each of the outcome themes, YWPD highlighted the influence of parents, peers, and coaches, as well as experiences that fostered independence, success, relatedness, and challenge; suggesting that these experiential elements may be instrumental in promoting PYD outcomes. These findings align with the notion of PYD climate (Holt et al., 2017) and share conceptual links with elements of mastery, challenge, belonging, and autonomy from the QP framework (Evans et al., 2018).

Theme Two: PYD Climate – The Importance of Parents, Peers, and Coaches

Theme two reflects the roles that parents, peers, and coaches played in shaping a social climate that contributed to the outcomes that YWPD acquired through sport. Theme two is comprised of the following three subthemes: a) providing support and encouragement, b) facilitating athletic development, and c) promoting a sense of community and connectedness.

Providing Support and Encouragement

Consistent with the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017), participants expressed that important social agents (i.e., parents, peers, and coaches) created a supportive environment by believing in them, “always being there”, providing words of encouragement (e.g., cheering), and recognizing their achievements. According to YWPD, this type of social support facilitated PYD outcomes through bolstered feelings of competence, belonging, and enjoyment:

Well, you know it influences my sport career significantly… if I had not had a great father, great coaches, and great teammates I would have never wanted to play this sport because you know, it’s ya… um they all you know they support me. They help out and make me feel part of a community which is a big part of my playing experience (P3, M, Age 16, Wheelchair Rugby).

Indeed, coaches provided an important source of support and encouragement, which was illustrated by the way athletes spoke about their coaches and/or instructors believing in them, always being there, and making them feel like they could accomplish anything. As one athlete explained:

Well I have a coach that’s pretty big on positivity and like making you feel like you can always accomplish something like you can always do it if you try hard enough. He’s always encouraging us to do better, to train properly, eat like really good, like do things to make us better (P6, F, Age 17, Wheelchair Basketball and Track & Field – Throwing).

This finding resonates with research among with (Turnnidge et al., 2012) and without disabilities (Fraser-Thomas & Côté, 2009), which suggests that supportive coaches can bolster athletes’ perceptions of competence by believing in them and expressing confidence in their abilities. YWPD also reported that peers positively impacted their sport experiences by providing an important source of social support through encouragement. For example,

One of my swim teammates, [teammate’s name], like I was nervous to go off the… sit on the block and do a sitting dive on the block and then I said to my mom I can’t do this. And then she [teammate] said, yes you can (P2, F, Age 14, Swimming).

This type of support has been shown to benefit the sport experiences of YWPD by enhancing their sense of connectedness with peers (e.g., displaying genuine care for each other’s success and accomplishments), as well as by helping them take on challenging tasks and overcome difficult situations (Turnnidge et al., 2012), which was also evident among YWPD in the current study.

Participants specifically commented about the unwavering support of parents (and family) through transportation, financial support (e.g., buying equipment), searching for sport opportunities, and involvement as a coach, assistant, spectator, or participant. According to YWPD, this support led to reassurance in their ability to participate safely, confidently, and successfully:

They [parents] supported me through games, they sat through horrible weather to watch me play. And just like their dedication and their support made me like, “k I’m doing the right thing by playing this sport” because they’re not like not showing up you know what I mean? Like they’re there coming to games, they’re supporting me and stuff like that and that helped me to be like, “ok I can play the sport how I want to play, because I have people behind me that support me regardless” (P8, M, Age 21, Soccer).

The PYD through sport model suggests that parent involvement may reinforce PYD by complementing and supporting the delivery of sport programs (e.g., engaging in discussions that help reinforce skills and lessons learned through sport; Holt et al., 2017). Comparatively, YWPD highlighted the importance of parent support and involvement in terms of facilitating positive sport experiences and directly affecting access to quality sport opportunities (Bloemen et al., 2015; Canadian Disability Participation Project, 2018a; Turnnidge et al., 2012; Wickman, 2015). Accordingly, parents may have reinforced PYD by creating opportunities for quality sport participation that may have otherwise been unfeasible.

These findings highlight the value of positive and supportive coach and peer relationships, as well as healthy parent involvement within sport (Holt et al., 2017), as this may promote PYD outcomes through strengthened feelings of competence, belonging, and enjoyment. Although supportive relationships are important to facilitate PYD outcomes among all youth sport participants (Holt et al., 2017), this work highlights the critical nature of this support for YWPD and speaks to the nuanced nature of support relationships for YWPD participating in sport (Javorina et al., 2021). Resources that support parents and coaches in facilitating positive relationships are desired and may help them to foster inclusive environments that optimize participation and outcomes for YWPD (Javorina et al., 2021).

Facilitating Athletic Development

YWPD explained that coaches and peers facilitated athletic development by creating opportunities to feel appropriately challenged, independent, and successful. According to participants, coaches contributed to several positive outcomes by setting high and achievable expectations, being attentive to the needs and abilities of YWPD, and providing assistance or adapting activities accordingly. For example,

They [instructors] can modify if it’s too challenging for my left hand. For like for our front crawl for example, like instead of just moving, circling both my arms out of the water I can just move my weak hand around in the water. When things get modified it makes it easier for me. Makes me feel like I can do everything everyone else can do (P1, M, Age 18, Swimming and Goal Ball).

When coaches can effectively assess and respond to the needs and abilities of athletes, they create safe and enjoyable opportunities for YWPD to test their limits, exert their independence, and experience success, which can foster positive self-perceptions, competence, and autonomy (Bloemen et al., 2015; Orr et al., 2018; Shirazipour et al., 2018; Turnnidge et al., 2012). Many of these experiential aspects of sport participation are highlighted in the QP framework (e.g., mastery, autonomy, challenge; Evans et al., 2018). In some cases, coaches may have contributed to negative outcomes (e.g., feeling frustrated, discouraged, embarrassed, left out) when they failed to provide appropriate adaptations, set low expectations, or made assumptions about the abilities of their athletes. For example,

They [coaches] think that they… that I cannot do stuff that I can try to do. And they lower the bar of expectations. My mom pushes me harder than my coaches do because they think I can’t do it. I think I would do much better if they pushed me harder like my mom does (P2, F, Age 14, Swimming).

Such negative experiences can jeopardize sport participation among YWPD by thwarting perceptions of autonomy, belongingness, and competence (Bantjes et al., 2015; Orr et al., 2018) which are highlighted in the QP framework as foundational to positive sport experiences for people with disabilities (Evans et al., 2018). Developing strong, positive coach-athlete relationships may be critically important in helping coaches get to know their athletes’ abilities and goals to ensure that expectations are set at a level that is appropriate for YWPD (Canadian Disability Participation Project, 2018a).

YWPD in the study described receiving important guidance, support, and feedback from peers, as well as experiencing opportunities to develop teamwork and leadership skills (e.g., teaching and helping others). They also noted that seeing peers perform skills or achieve goals motivated them to push themselves, work hard, and take on challenges:

Well people that umm have my disability that umm… have the same struggles that I do and um seeing them…ya know seeing them is kind of a motivation. They can accomplish such and such and I can do as well, so yeah (P3, M, Age 16, Wheelchair Rugby).

Indeed, coaches and peers can create opportunities for YWPD to experience challenge, autonomy, and mastery within sport (Evans et al., 2018; Shirazipour et al., 2018; Turnnidge et al., 2012). Sport contexts that encourage peer leadership and role-modeling can positively impact youth development (Eccles et al., 2003; Fujimoto et al., 2018; Holt et al., 2017). As such, it may be critical to ensure that coaches possess the skills, training, and supports necessary to facilitate these experiences, as well as to encourage opportunities for peer-leadership and role-modeling within sport, as a means of shaping a PYD climate that promotes positive outcomes.

Promoting a Sense of Community and Connectedness

Strong and enduring peer relationships are thought to contribute to the creation of a PYD climate by fostering “feelings of belonging to a wider community” (Holt et al., 2017, p. 33). YWPD indicated that strong peer- and coach-relationships, as well as parental involvement, promoted a sense of community (i.e., belonging to something “bigger than oneself”) and connectedness. For example, YWPD revealed that coaches contributed to a sense of belonging by being kind, relatable, and expressing an interest in getting to know and connect with their athletes. “I think she’s there also as a friend [instructor] … At our lunch time we kinda sit with her, we chat with her, we talk and we can just… she’s there for us” (P4, M, Age 15, Wheelchair Tennis and Adapted Skiing).

Coaches have been shown to foster feelings of social connection and belonging among athletes with disabilities by developing supportive and caring coach-athlete relationships (Shirazipour et al., 2017). Furthermore, there is a link between athletic competence and peer acceptance (Jones et al., 2011) such that coaches may have also promoted a sense of belonging by creating opportunities for YWPD to feel enabled and competent.

YWPD felt a sense of belonging when they engaged in shared experiences with peers (e.g., playing and having fun together, celebrating each other’s success). Many participants explained that feelings of belonging were enhanced when they participated among “similar peers” (i.e., also living with a disability), because they could more easily relate to them.

So, I met all these people in track and field and basketball I had more in common with them, I felt like I could relate to them and what they’ve gone through their whole life. Their life is so similar to mine. So, I dunno, we connected more I think than I would have with anyone else (P6, F, Age 17, Wheelchair Basketball and Track & Field—Throwing).

There is value in providing opportunities for athletes with disabilities to participate among peers who share similar experiences and impairments, as these could foster a greater acceptance and understanding within the sport environment (Turnnidge et al., 2012), and thus enhance perceptions of belonging (Shirazipour et al., 2018). YWPD also expressed enjoyment in having parents and family members actively involved in their sport experience (e.g., as a coach, trainer, spectator, or participant), because it created opportunities for them to spend time and have fun together.

I started skiing when I… last year. I fell in love with it. It was something I can do, my brother can do, and my mom can do. I could ski with them; I just needed a little help, but it was so much fun. I can talk about how the snow was so light and we can all relate to how it feels to be outside in the wilderness skiing, socializing, and having the times of our lives (P7, M, Age 15, Sledge Hockey and Adapted Skiing).

In addition to facilitating participation, parent (and family) support and involvement can promote feelings of social connection and belonging within sport (Evans et al., 2018; Shirazipour et al., 2017; Turnnidge et al., 2012). Consistent with the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017), belongingness may be an essential component of a sport context that promotes PYD outcomes among YWPD. Furthermore, a sense of belonging may provide YWPD with positive sport experiences that facilitate optimal outcomes (Evans et al., 2018) and may be achieved through experiences that cultivate strong connections with peers, as well as with coaches, and parents.

The Future of PYD Through Sport among YWPD, an Integrated Approach?

This study adds to the limited current literature by suggesting that PYD may provide a viable approach for understanding development through sport among YWPD. Although the PYD through sport model (Holt et al., 2017) served as the guiding framework for the current study, the participants highlighted elements of mastery, belonging, challenge, and autonomy from the QP framework (Evans et al., 2018), which may be critical to consider in pursuing further understanding of sport outcomes and experiences among YWPD. For instance, integrating QP concepts (e.g., mastery, challenge, autonomy, belonging) with traditional PYD models (e.g., Holt et al., 2017) may uncover mechanisms of PYD facilitation specific to YWPD. As such, future research may consider exploring the QP framework in the context of PYD. Perhaps when parents, peers, and coaches foster “quality experiences” (i.e., opportunities to experience a sense of belonging, mastery, autonomy, challenge, meaning, and engagement; Evans et al., 2018), they create a PYD climate through which YWPD can gain positive outcomes. In contrast, YWPD may experience negative outcomes if the social climate of sport does not support these aspects of quality participation. The QP framework primarily focuses on understanding the processes that promote quality parasport participation (Evans et al., 2018). The current study also extends the utility of the QP framework by identifying potential outcomes that may result from fostering or hindering quality participation. An integrated approach may further an understanding of the experiences that contribute to an optimal climate through which YWPD can develop PYD outcomes, as well as uncover the potential positive outcomes that come from fostering “quality experiences” through sport.

Pragmatically, there may be value in adopting an integrated approach to explore PYD through sport among YWPD. For instance, the Blueprint for Building Quality Participation in Sport for Children, Youth, and Adults with a Disability (2018) is an evidence-based tool grounded in principles from the QP framework that was developed to inform program builders (e.g., administrators, coaches and policy makers) about strategies to foster belonging, autonomy, mastery, challenge, engagement, and meaning in sport (Canadian Disability Participation Project, 2018b). Since this tool has been used to inform programs that promote quality sport experiences, a novel first step could be to assess its use in promoting positive outcomes among YWPD within the context of a PYD framework (e.g., Holt and colleagues’ model; 2017).

Strengths, Limitations and Future Research Considerations

A major strength of the current study was the diversity of participants’ sport experiences. The diverse experiences allowed for consideration of outcomes across a wide range of sports (e.g., goalball, wheelchair basketball, rugby, and tennis, adapted skiing, sledge hockey, swimming, track and field and soccer) and levels (e.g., recreational, competitive, provincial, and national). Furthermore, findings were drawn from participants’ positive and negative sport experiences, which broadens an understanding of how sport participation may promote or hinder positive development among YWPD.

Because the sample did not include YWPD who withdrew from sport, the findings may have been positively biased. To address this limitation and expand on the potential factors hindering PYD through sport, it would be valuable to hear the voices of YWPD who had particularly negative experiences and withdrew from sport. It would also be interesting to understand the similarities (and differences) in youth and adult parasport experiences. Future research should also look to further contextualize the sport experiences of YWPD in relation to aspects of various sport programs (e.g., age of peers/teammates, level of experience of coaches). It was beyond the scope of the current study to understand the impact of individual (e.g., level of impairment or disability) and broader contextual factors on PYD (e.g., institutional, community, and policy). These factors likely contribute to parasport experiences and outcomes (Martin Ginis et al., 2016) and future research should examine how these factors may facilitate or hinder PYD through sport among YWPD. It may be valuable to explore the perspectives of parents and program providers, alongside those of YWPD, to gain insight regarding how the availability and accessibility of sport programs (e.g., parents’ perspective) and program design and delivery (e.g., program provider’s perspective) may influence YWPD sport experiences and outcomes.

CONCLUSION

This study explored the sport experiences of YWPD through a PYD lens to understand outcomes associated with organized sport participation and the social-contextual factors influencing these outcomes. Findings suggest that organized sport may serve as a context through which YWPD can experience a wide range of positive outcomes, including life skill development and transfer, provided that a PYD climate is in place and experiences of mastery, autonomy, challenge, and belonging are fostered. Furthermore, this study supports the use of PYD as a viable approach for enhancing an understanding of how organized sport participation may contribute to positive or negative developmental outcomes among YWPD. Since the study findings shared strong conceptual links with the QP framework (Evans et al., 2018), it is encouraged that future research adopt an integrated approach to inform a better understanding of how organized sport can be utilized as a vehicle to promote PYD among YWPD.

REFERENCES

Allan, V., Evans, B. M., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., & Côté, J. (2020) From the athletes’ perspective: A social-relational understanding of how coaches shape the disability sport experience. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(6), 546-564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2019.1587551

Bagnoli, A. (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547-570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109343625

Bantjes, J., Swartz, L., Conchar, L., & Derman, W. (2015). Developing programmes to promote participation in sport among adolescents with disabilities: Perceptions expressed by a group of South African adolescents with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 62(3), 288-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2015.1020924

Bloemen, M. A. T., Backx, F. J. G., Takken, T., Wittink, H., Benner, J., Mollema, J., & de Groot, J. F. (2015). Factors associated with physical activity in children and adolescents with a physical disability: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 57(2), 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12624

Bragg, E., & Pritchard-Wiart, L. (2019). Wheelchair physical activities and sports for children and adolescents: A scoping review. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 39(6), 567-579. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2019.1609151

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., Clarke, V. & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise (pp. 191-205). Routledge.

Buffart, L. M., van der Ploeg, H. P., Bauman, A. E., Van Asbeck, F. W., Stam, H. J., Roebroeck, M. E., & van den Berg-Emons, R. J. (2008). Sports participation in adolescents and young adults with myelomeningocele and its role in total physical activity behaviour and fitness. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 40(9), 702-708. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0239

Canadian Disability Participation Project. (2018a). Evidence-based strategies for building quality participation in sport for children, youth, and adults with a disability. https://cdpp.ca/sites/default/files/CDPP%20Quality%20of%20Participation%20Evidence%20Summary.pdf

Canadian Disability Participation Project. (2018b). A blueprint for building quality participation in sport for children, youth, and adults with a disability. https://cdpp.ca/sites/default/files/CDPP%20Quality%20of%20Participation%20Blueprint%20Jan%202020.pdf

Cottingham, M., Carroll, M., Lee, D., Shapiro, D., & Pitts, B. (2016). The historical realization of the Americans with disabilities act on athletes with disabilities. Journal of Legal Aspects Sport, 26(1), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1123/jlas.2015-0014

Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 865-889. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x

Evans, B. M., Shirazipour, C. H., Allan, V., Zanhour, M., Sweet, S. N., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Integrating insights from the parasport community to understand optimal experiences: The Quality Parasport Participation Framework. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 37, 79-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.04.009

Fraser-Thomas, J., & Côté, J. (2009). Understanding adolescents’ positive and negative developmental experiences in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 23(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.23.1.3

Fraser-Thomas, J. L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2005). Youth sport programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 10(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898042000334890

Fujimoto, K., Snijders, T. A. B., & Valente, T. W. (2018). Multivariate dynamics of one-mode and two-mode networks: Explaining similarity in sports participation among friends. Network Science, 6(3), 370-395. https://doi.org/10.1017/nws.2018.11

Gould, D., & Carson, S. (2008). Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1),58-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840701834573

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 105-117). SAGE.

Holt, N. L., & Neely, K. C. (2011). Positive youth development through sport: A review. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología del Ejercicio y el Deporte, 6(2), 299-316.

Holt, N. L., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., McDonald, D., Strachan, L., & Tamminen, K. A. (2017). A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 1-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704

Jaarsma, E. A., Dijkstra, P. U., De Blécourt, A. C. E., Geertzen, J. H. B., & Dekker, R. (2015). Barriers and facilitators of sports in children with physical disabilities: A mixed-method study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(18), 1617-1625. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.972587

Javorina, D., Shirazipour, C. H., Allan, V., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2021). The impact of social relationships on initiation in adapted physical activity for individuals with acquired disabilities. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, Article 101929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101929

Jones, M., Dunn, J.G., Holt, N. L., Sullivan, P. J., & Bloom, G. A. (2011). Exploring the ‘5Cs’ of positive youth development in sport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 34(3), 250-267.

Kingsnorth, S., Healy, H., & Macarthur, C. (2007). Preparing for adulthood: A systematic review of life skill programs for youth with physical disabilities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(4), 323-332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.007

Klenk, C., Albrecht, J., & Nagel., S. (2019). Social Participation of people with disabilities in organized community sport: A systematic review. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 49(4), 365-380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-019-00584-3

Leo, J. A., Faulkner, G., Volfson, Z., Bassett-Gunter, R., & Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. (2018). Physical activity preferences, attitudes, and behaviour of children and youth with physical disabilities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 52(2), 140-153. https://doi.org/10.18666/TRJ-2018-V52-I2-8443

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Lower-Hoppe, L. M., Anderson-Butcher, D., Newman, T. J., & Logan, J. (2021). The influence of peers on life skill development and transfer in a sport-based positive youth development program. Journal of Sport for Development, 9(2), 69-85.

Marques, A., Ekelund, U., & Sardinha, L. B. (2016). Associations between organized sports participation and objectively measured physical activity, sedentary time and weight status in youth. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 19(2), 154-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.007

Martin, J. J. (2011). Disability youth sport participation: Health benefits, injuries, and psychological effects. In A. D. Farelli (Eds.), Sport Participation: Health Benefits, Injuries and Psychological Effects (pp. 105-121). Nova Science Publishers.

Martin, J. J., & Mushett, C. A. (1996). Social support mechanisms among athletes with disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 13(1), 74-83. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.13.1.74

Martin, J. J., & Whalen, L. (2014). Effective practices of coaching disability sport. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 7(2), 13-23.

Martin Ginis, K. A., Ma, J. K., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., & Rimmer, J. H. (2016). A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychology Review, 10(4), 478-494. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1198240

McLoughlin, G., Fecske, C. W., Castaneda, Y., Gwin, C., & Graber, K. (2017). Sport participation for elite athletes with physical disabilities: Motivations, barriers, and facilitators. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(4), 421-441. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2016-0127

Molik, B., Zubala, T., Slyk, K., Bigas, G., Gryglewicz, A., & Kucharczyk, B. (2010). Motivation of the disabled to participate in chosen Paralympics events (wheelchair basketball, wheelchair rugby, and boccia). Fizjoterapia, 18(1), 42-51. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10109-010-0044-5

Murphy, N. A., Carbone, P. S., & Council on Children with Disabilities (2008). Promoting the participation of children with disabilities in sports, recreation, and physical activities. Pediatrics, 121(5), 1057-1061. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0566

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Orr, K., Tamminen, K. A., Sweet, S. N., Tomasone, J. R., & Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P. (2018). “I’ve had bad experiences with team sport”: Sport participation, peer need-thwarting, and need-supporting behaviors among youth identifying with physical disability. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 35(1), 36-56. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2017-0028

Petitpas, A. J., Cornelius, A. E., Van Raalte, J. L., & Jones, T. (2005). A Framework for planning youth sport programs that foster psychosocial development. The Sport Psychologist, 19(1), 63-80. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.1.63

Pierce, S., Gould, D., & Camiré, M. (2017). Definition and model of life skills transfer. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 186-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1199727

Rimmer, J. H. (2001). Physical fitness levels of persons with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 43(3), 208-212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2001.tb00189.x

Roth, J., Brooks-Gunn, J., Murray, L., & Foster, W. (1998). Promoting healthy adolescents: Synthesis of youth development program evaluations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(4), 423-59. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0804_2

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Shapiro, D. R., & Martin, J. J. (2010). Athletic identity, affect, and peer relations in youth athletes with physical disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 3(2), 79-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.08.004

Shapiro, D. R., & Martin, J. J. (2014). The relationships among sport self-perceptions and social well-being in athletes with physical disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 7(1), 42-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.06.002

Shields, N., & Synnot, A. (2016). Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatrics, 16, Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0544-7

Shirazipour, C. H., Evans, M. B., Caddick, N., Smith, B., Aiken, A. B., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2017). Quality participation experiences in the physical activity domain: Perspectives of veterans with a physical disability. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.007

Shirazipour, C. H., Evans, M. B., Leo, J., Lithopoulos, A., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Program conditions that foster quality physical activity participation experiences for people with a physical disability: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(2), 147-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1494215

Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101-121. http://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

te Velde, S. J., Lankhorst, K., Zwinkels, M., Verschuren, O., Takken, T., & de Groot, J. (2018). Associations of sport participation with self-perception, exercise self-efficacy and quality of life among children and adolescents with a physical disability or chronic disease-a cross-sectional study. Sports Medicine – Open, 4, Article 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-018-0152-1

Townsend, R. C., Smith, B., & Cushion, C. J. (2015). Disability sports coaching: Towards a critical understanding. Sports Coaching Review, 4(2), 80-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2016.1157324

Turnnidge, J., Vierimaa, M., & Coté, J. (2012). An in-depth investigation of a model sport program for athletes with a physical disability. Psychology, 3(12), 1131–1141. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312a167

Volfson, Z., McPherson, A., Tomasone, J. R., Faulkner, G. E., & Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P. (2020). Examining factors of physical activity participation in youth with spina bifida using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Disability and Health, 13(4), Article 100922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100922

Wickman, K. (2015). Experiences and perceptions of young adults with physical disabilities on sports. Social Inclusion, 3(3), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i3.158

Woodmansee, C., Hahne, A., Imms, C., & Shields, N. (2016). Comparing participation in physical recreation activities between children with disability and children with typical development: A secondary analysis of matched data. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 49–50, 268-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.12.004